Learning with Submodular Functions

Francis Bach Sierra project-team, INRIA - Ecole Normale Suprieure e

Machine Learning Summer School, Kyoto September 2012

Submodular functions are relevant to machine learning for mainly two reasons: (1) some problems may be expressed directly as the optimization of submodular functions and (2) the Lovasz extension of submodular functions provides a useful set of regularization functions for supervised and unsupervised learning. In this course, I will present the theory of submodular functions from a convex analysis perspective, presenting tight links between certain polyhedra, combinatorial optimization and convex optimization problems. In particular, I will show how submodular function minimization is equivalent to solving a wide variety of convex optimization problems. This allows the derivation of new efficient algorithms for approximate submodular function minimization with theoretical guarantees and good practical performance. By listing examples of submodular functions, I will also review various applications to machine learning, such as clustering or subset selection, as well as a family of structured sparsity-inducing norms that can be derived and used from submodular functions.

Scroll with j/k | | | Size

Learning with Submodular Functions

Francis Bach Sierra project-team, INRIA - Ecole Normale Suprieure e

Machine Learning Summer School, Kyoto September 2012

1

Submodular functions- References and Links

References based on from combinatorial optimization Submodular Functions and Optimization (Fujishige, 2005) Discrete convex analysis (Murota, 2003) Tutorial paper based on convex optimization (Bach, 2011) www.di.ens.fr/~fbach/submodular_fot.pdf Slides for this class www.di.ens.fr/~fbach/submodular_fbach_mlss2012.pdf Other tutorial slides and code at submodularity.org/ Lecture slides at ssli.ee.washington.edu/~ bilmes/ee595a_ spring_2011/

2

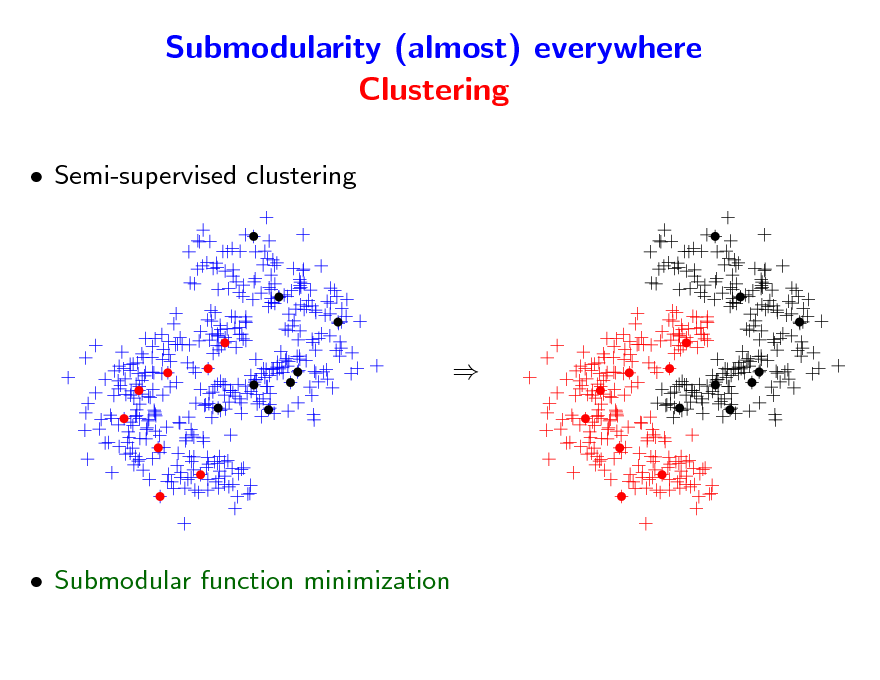

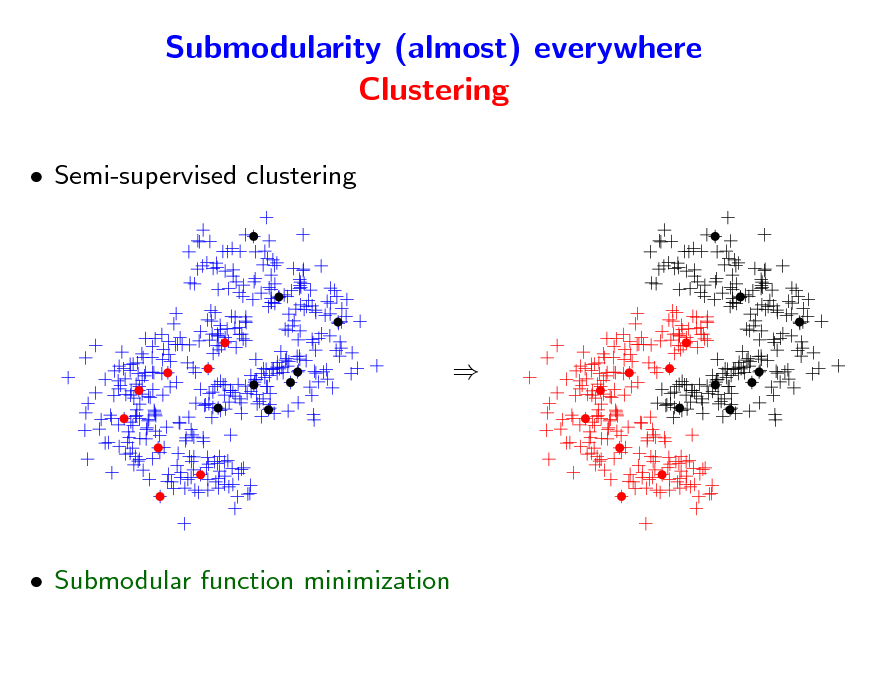

Submodularity (almost) everywhere Clustering

Semi-supervised clustering

Submodular function minimization

3

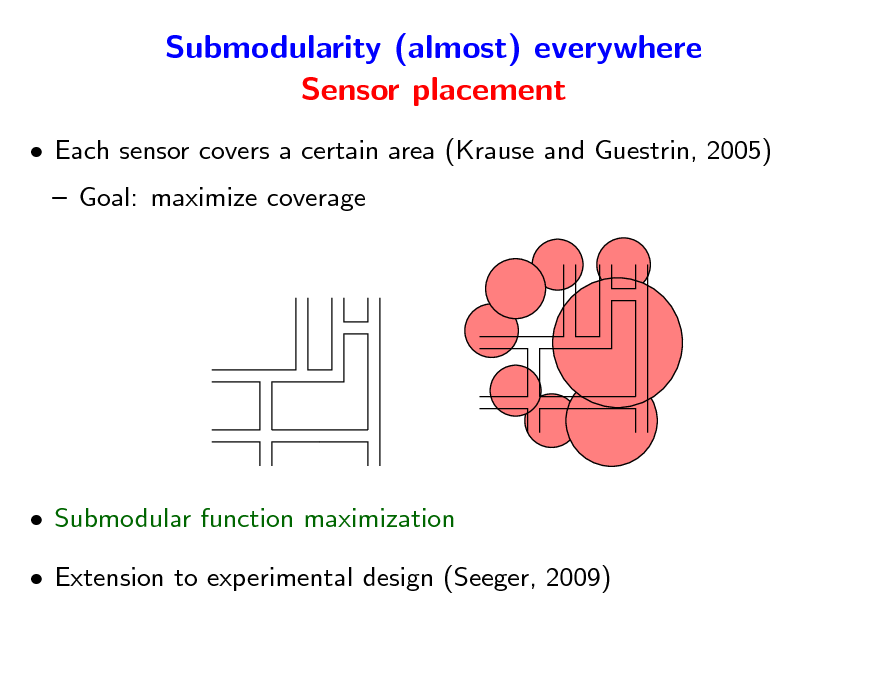

Submodularity (almost) everywhere Sensor placement

Each sensor covers a certain area (Krause and Guestrin, 2005) Goal: maximize coverage

Submodular function maximization Extension to experimental design (Seeger, 2009)

4

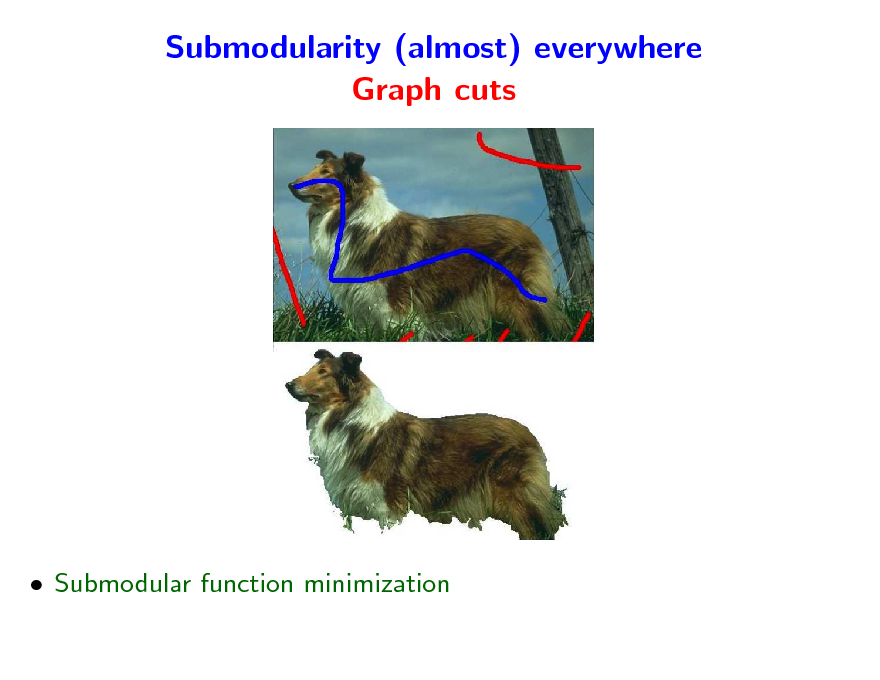

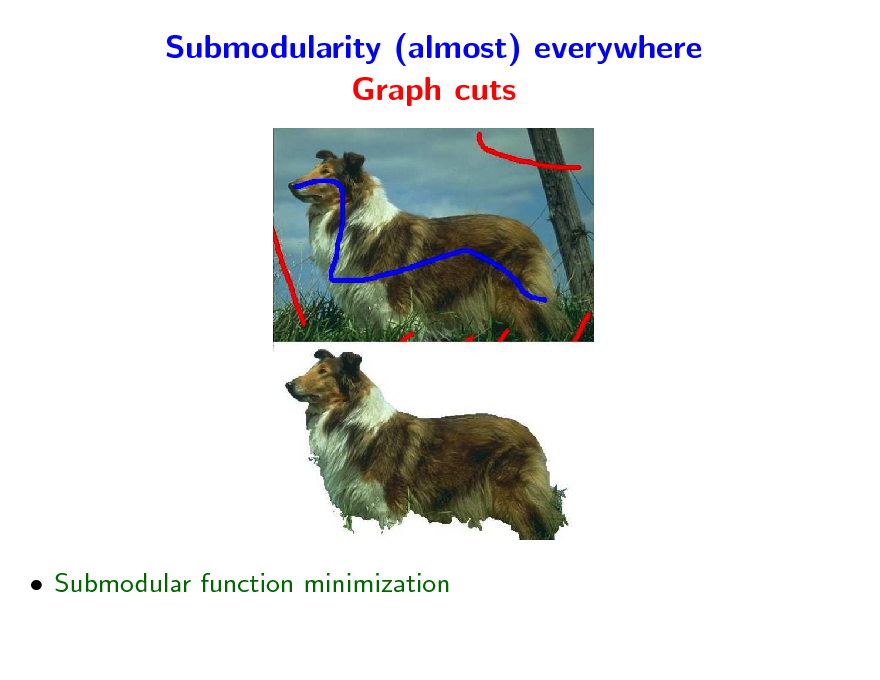

Submodularity (almost) everywhere Graph cuts

Submodular function minimization

5

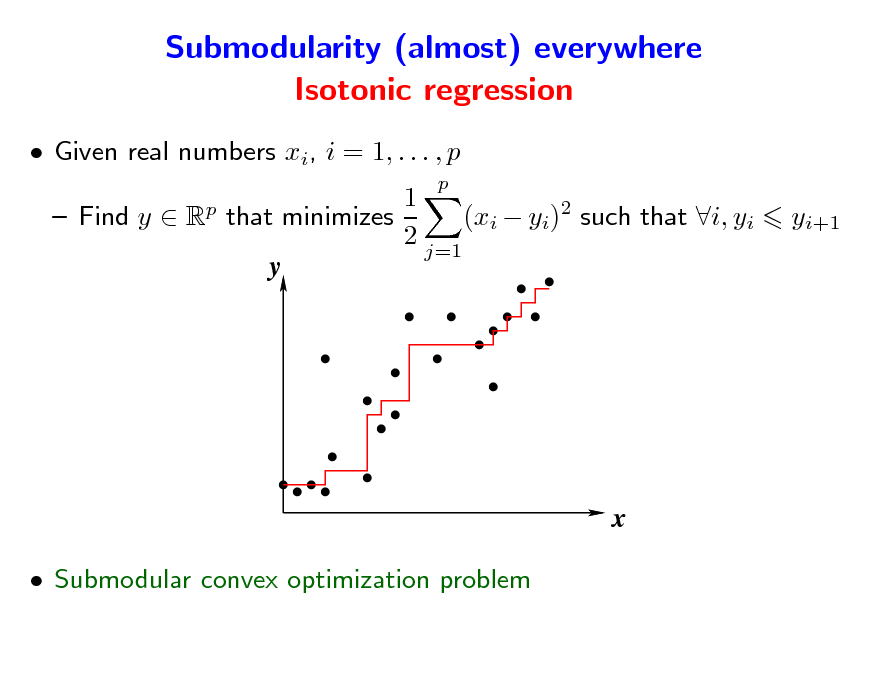

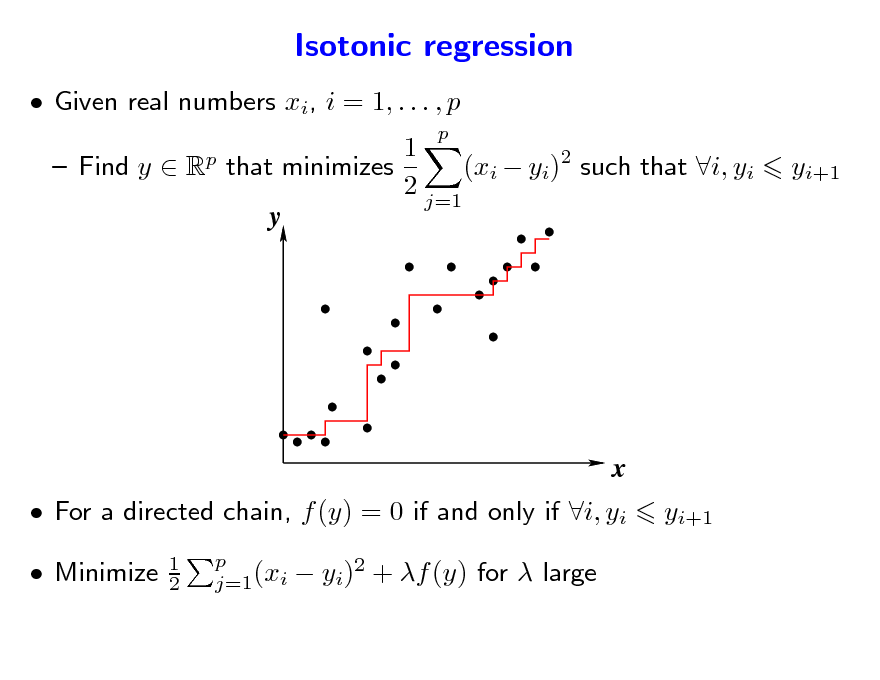

Submodularity (almost) everywhere Isotonic regression

Given real numbers xi, i = 1, . . . , p

p p

1 Find y R that minimizes (xi yi)2 such that i, yi 2 j=1 y

yi+1

x

Submodular convex optimization problem

6

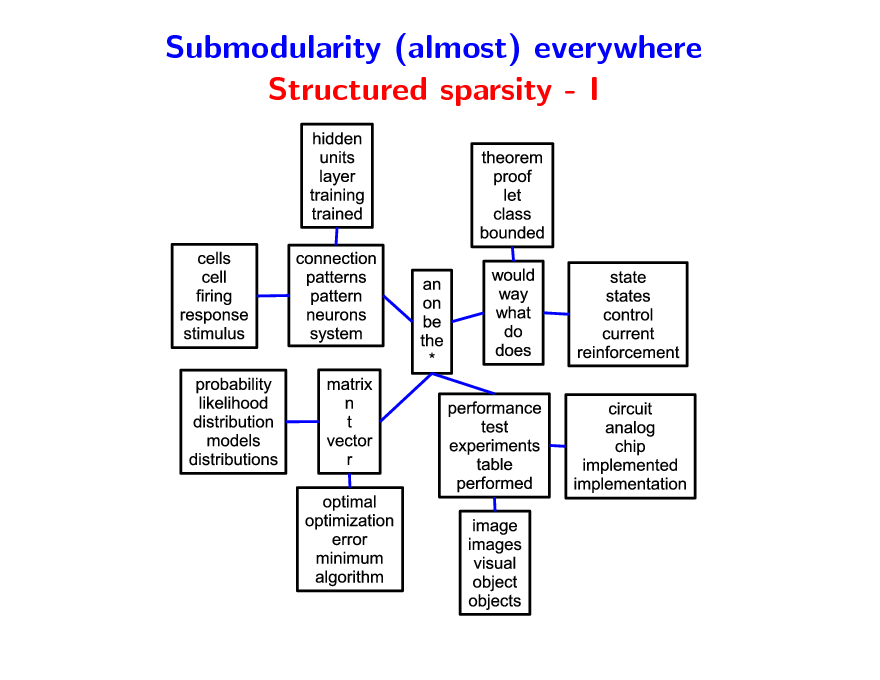

Submodularity (almost) everywhere Structured sparsity - I

7

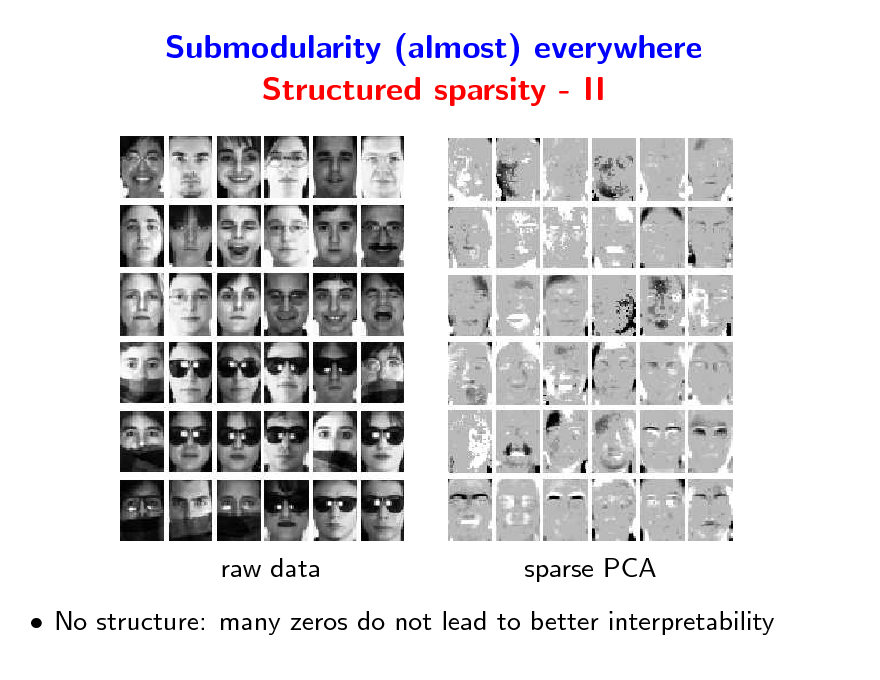

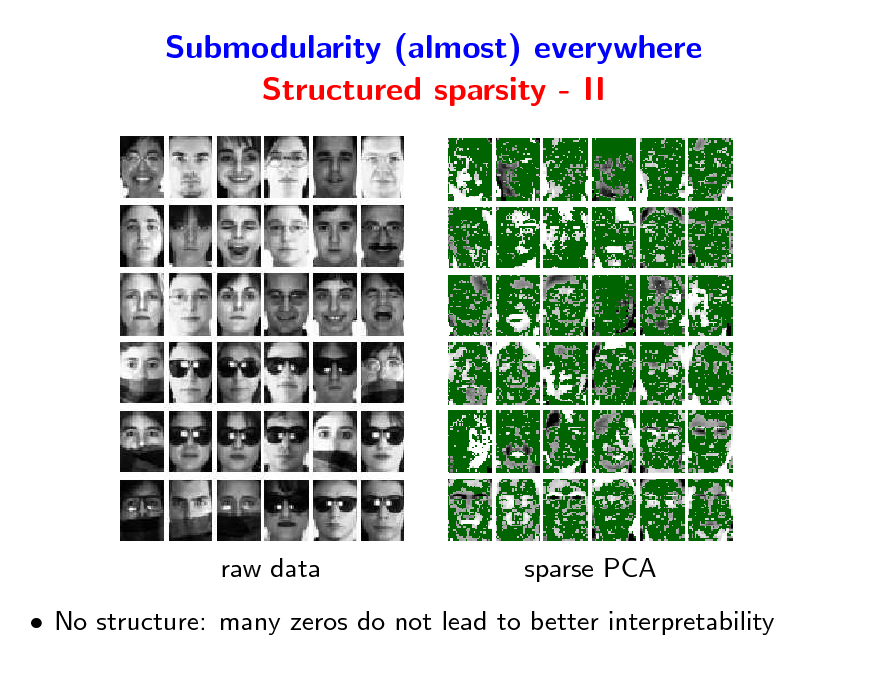

Submodularity (almost) everywhere Structured sparsity - II

raw data

sparse PCA

No structure: many zeros do not lead to better interpretability

8

Submodularity (almost) everywhere Structured sparsity - II

raw data

sparse PCA

No structure: many zeros do not lead to better interpretability

9

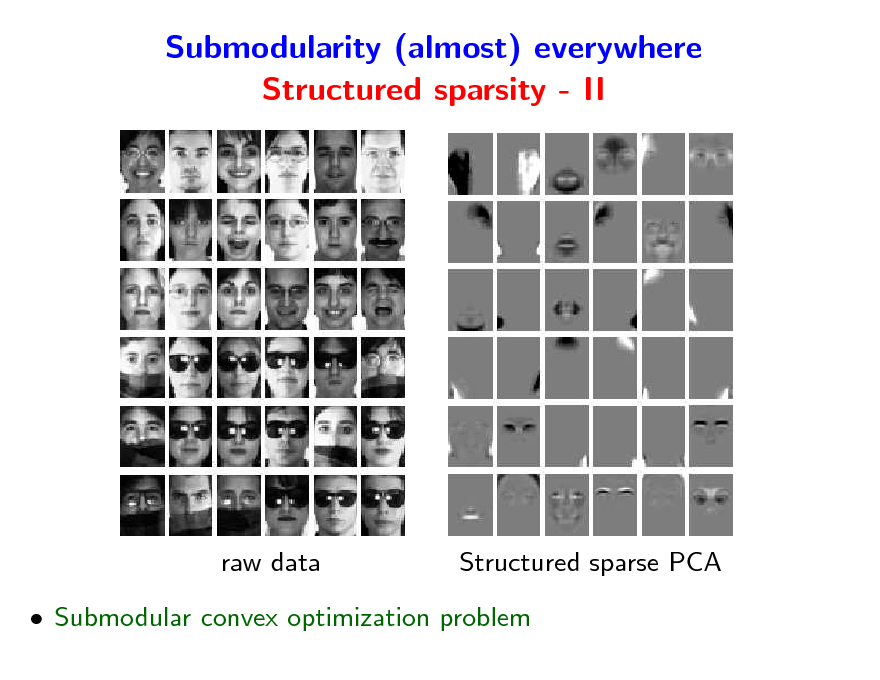

Submodularity (almost) everywhere Structured sparsity - II

raw data

Structured sparse PCA

Submodular convex optimization problem

10

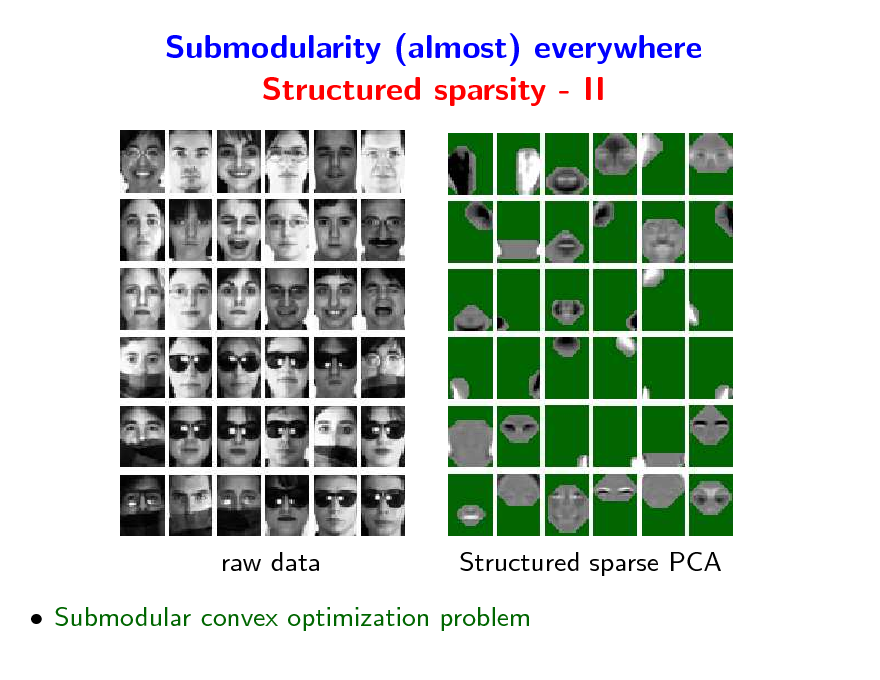

Submodularity (almost) everywhere Structured sparsity - II

raw data

Structured sparse PCA

Submodular convex optimization problem

11

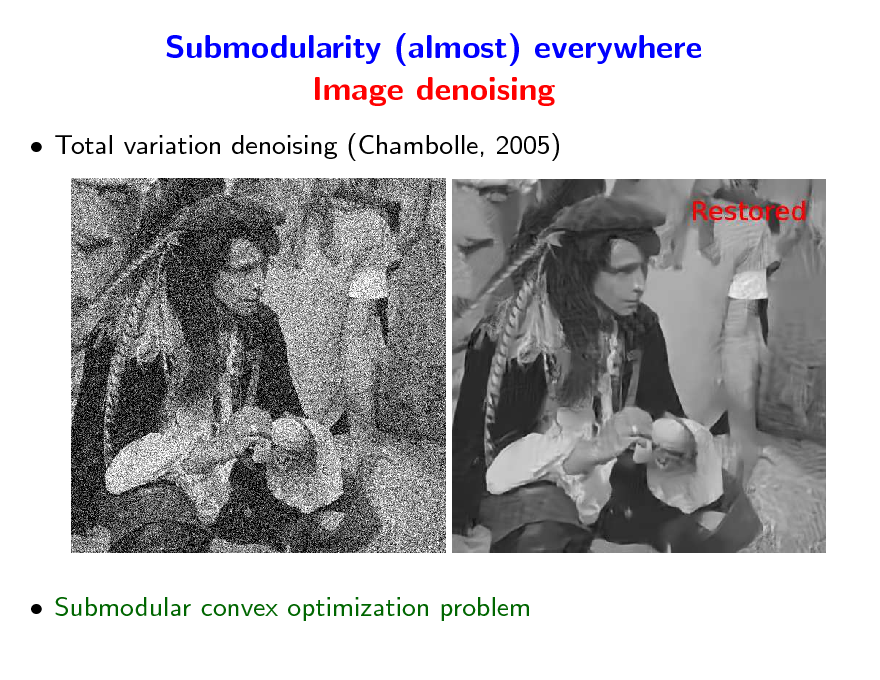

Submodularity (almost) everywhere Image denoising

Total variation denoising (Chambolle, 2005)

Submodular convex optimization problem

12

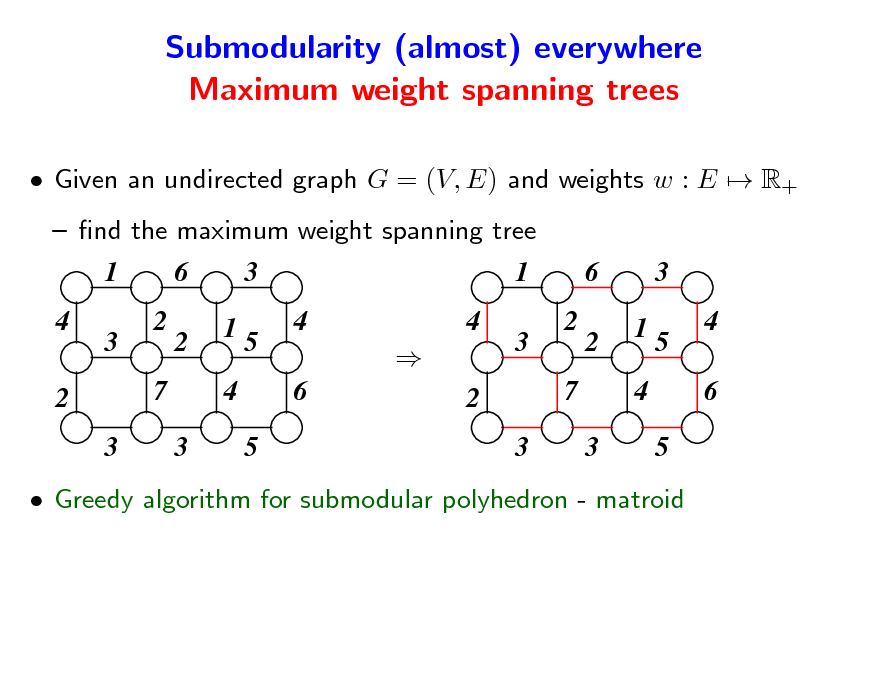

Submodularity (almost) everywhere Maximum weight spanning trees

Given an undirected graph G = (V, E) and weights w : E R+ nd the maximum weight spanning tree

1 4 2 3 3 2 7

6 2 1 4 3

3 5 4 6 5

1 4 2 3 3 2 7

6 2 1 4 3

3 5 4 6 5

Greedy algorithm for submodular polyhedron - matroid

13

Submodularity (almost) everywhere Combinatorial optimization problems

Set V = {1, . . . , p} Power set 2V = set of all subsets, of cardinality 2p Minimization/maximization of a set function F : 2V R.

AV

min F (A) = min F (A)

A2V

14

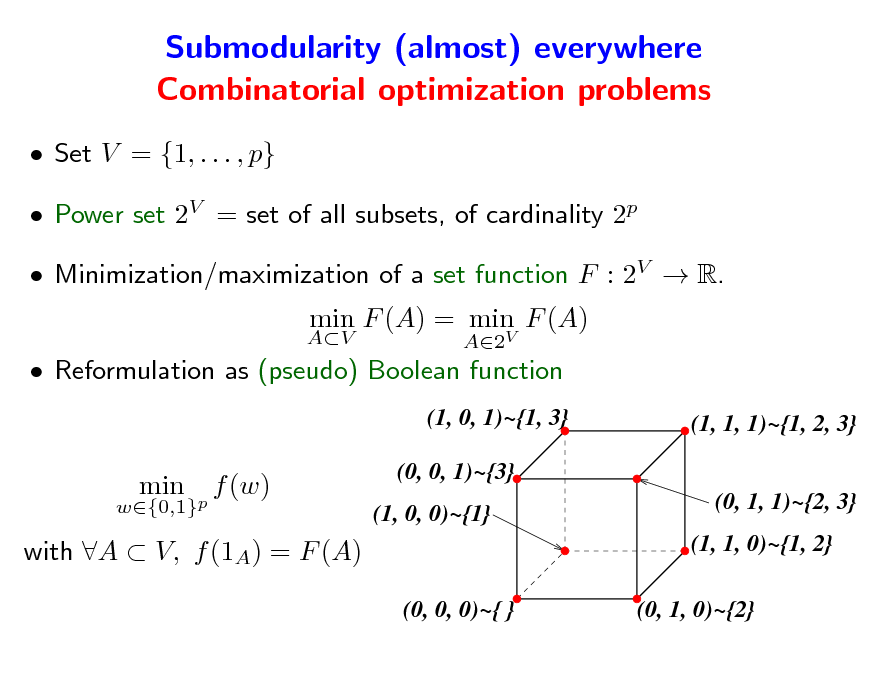

Submodularity (almost) everywhere Combinatorial optimization problems

Set V = {1, . . . , p} Power set 2V = set of all subsets, of cardinality 2p Minimization/maximization of a set function F : 2V R.

AV

min F (A) = min F (A)

A2V

Reformulation as (pseudo) Boolean function

(1, 0, 1)~{1, 3} (1, 1, 1)~{1, 2, 3} (0, 1, 1)~{2, 3} (1, 1, 0)~{1, 2} (0, 0, 0)~{ } (0, 1, 0)~{2}

w{0,1}p

min

f (w)

(0, 0, 1)~{3} (1, 0, 0)~{1}

with A V, f (1A) = F (A)

15

Submodularity (almost) everywhere Convex optimization with combinatorial structure

Supervised learning / signal processing Minimize regularized empirical risk from data (xi, yi), i = 1, . . . , n: 1 min (yi, f (xi)) + (f ) f F n i=1 F is often a vector space, formulation often convex Introducing discrete structures within a vector space framework Trees, graphs, etc. Many dierent approaches (e.g., stochastic processes) Submodularity allows the incorporation of discrete structures

n

16

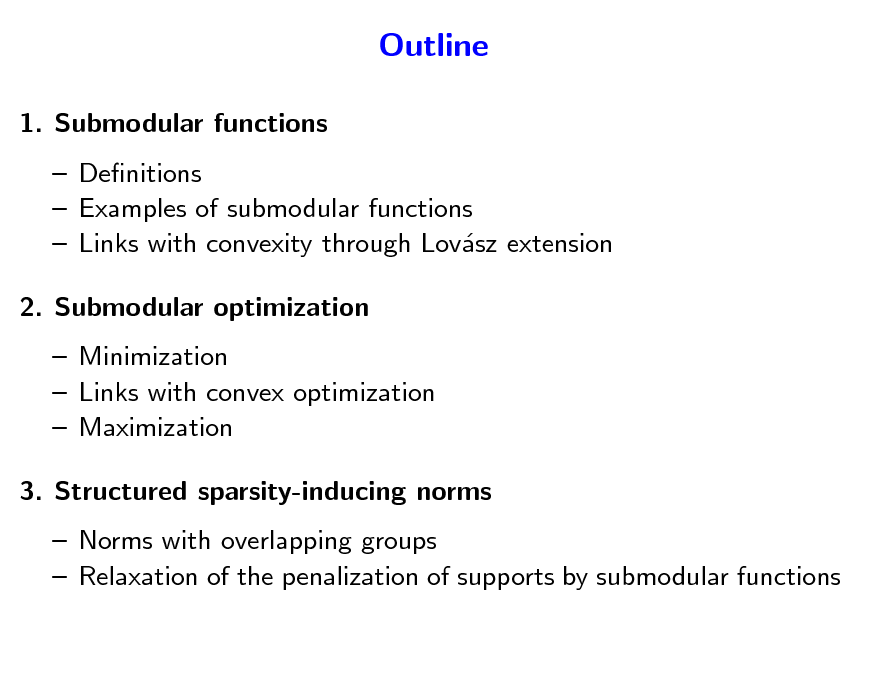

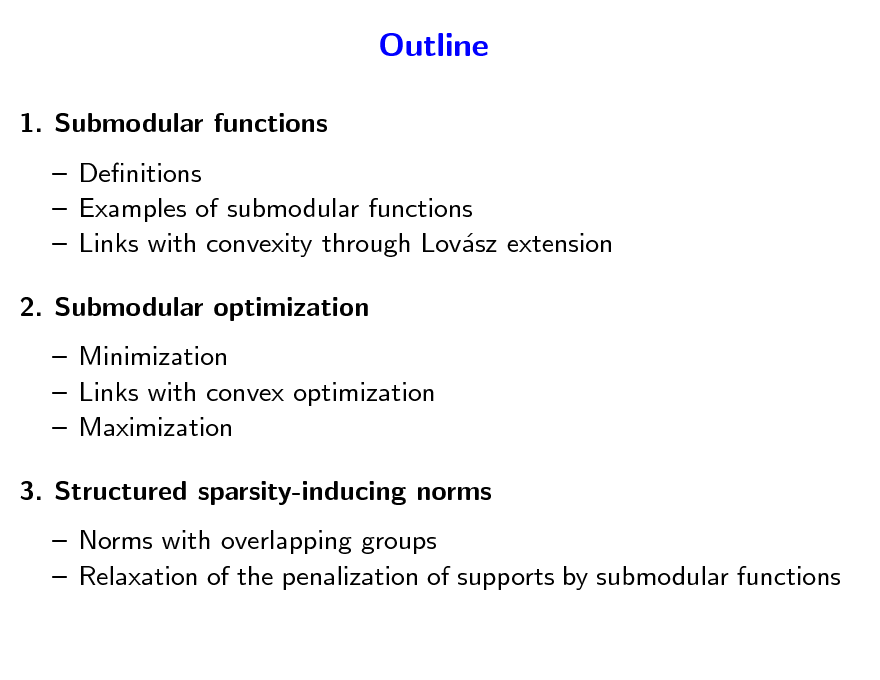

Outline

1. Submodular functions Denitions Examples of submodular functions Links with convexity through Lovsz extension a 2. Submodular optimization Minimization Links with convex optimization Maximization 3. Structured sparsity-inducing norms Norms with overlapping groups Relaxation of the penalization of supports by submodular functions

17

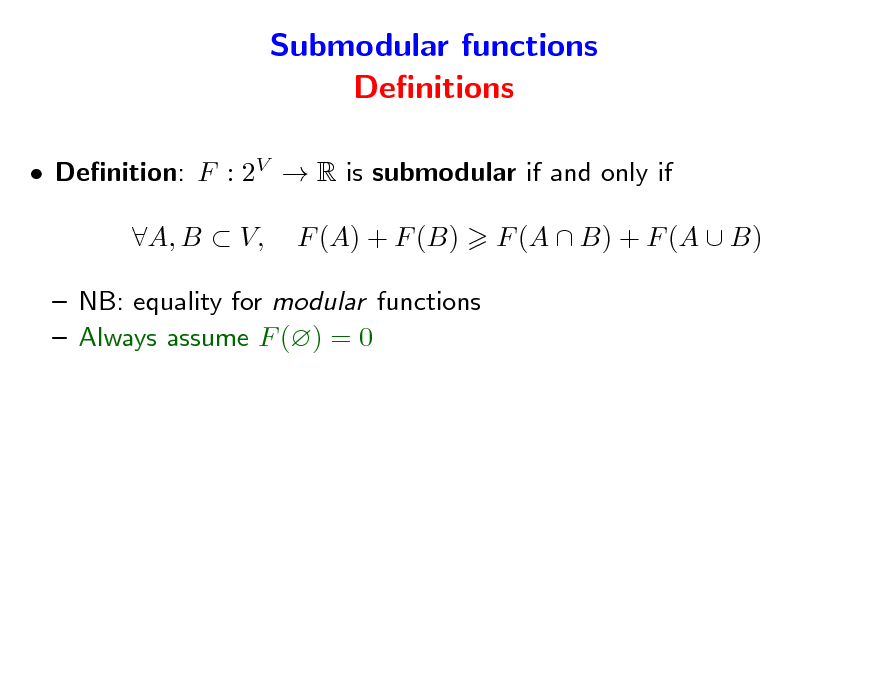

Submodular functions Denitions

Denition: F : 2V R is submodular if and only if A, B V, F (A) + F (B) F (A B) + F (A B)

NB: equality for modular functions Always assume F () = 0

18

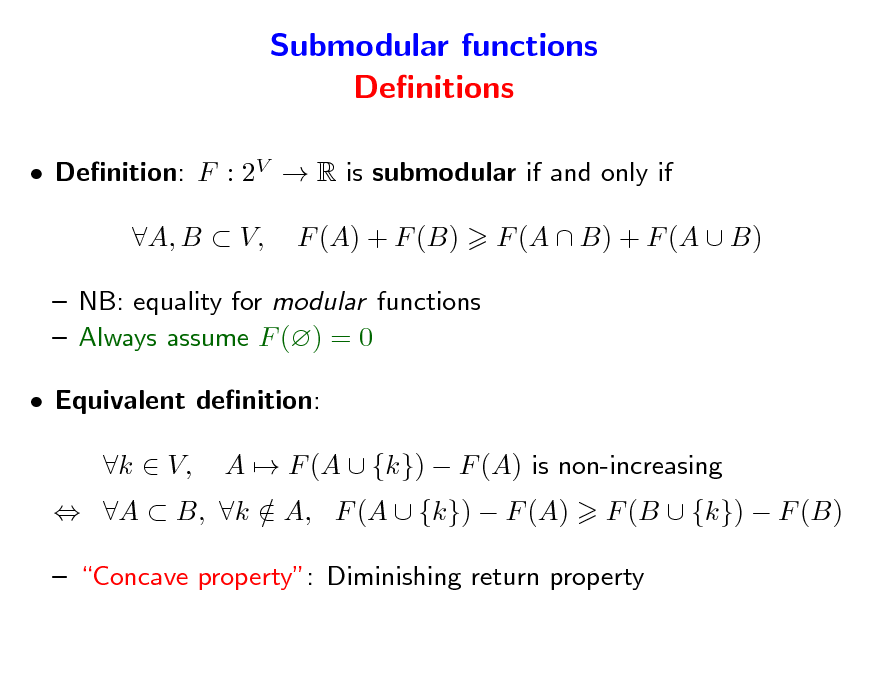

Submodular functions Denitions

Denition: F : 2V R is submodular if and only if A, B V, F (A) + F (B) F (A B) + F (A B)

NB: equality for modular functions Always assume F () = 0 Equivalent denition: A B, k A, F (A {k}) F (A) / k V, A F (A {k}) F (A) is non-increasing F (B {k}) F (B)

Concave property: Diminishing return property

19

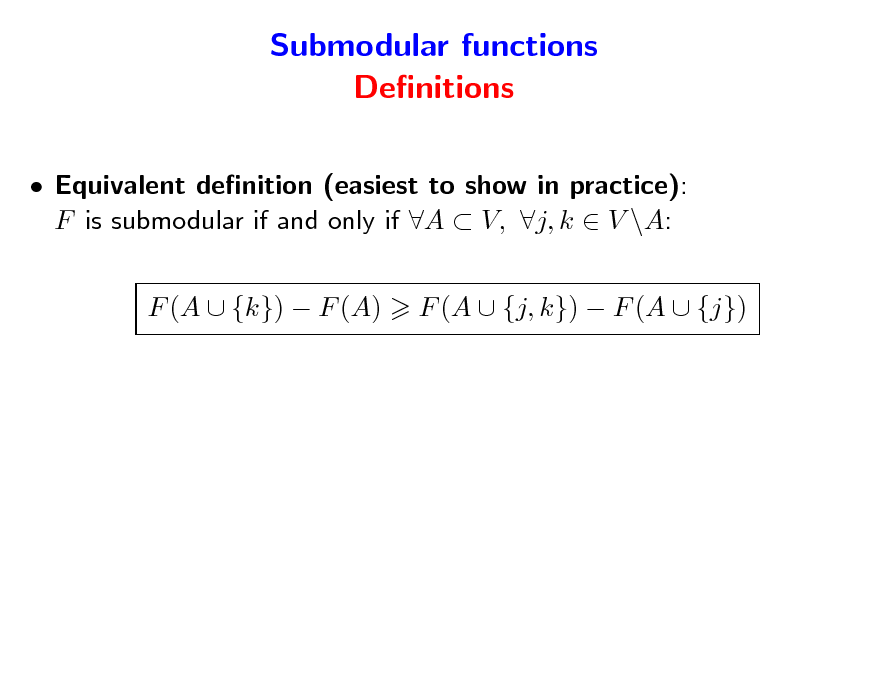

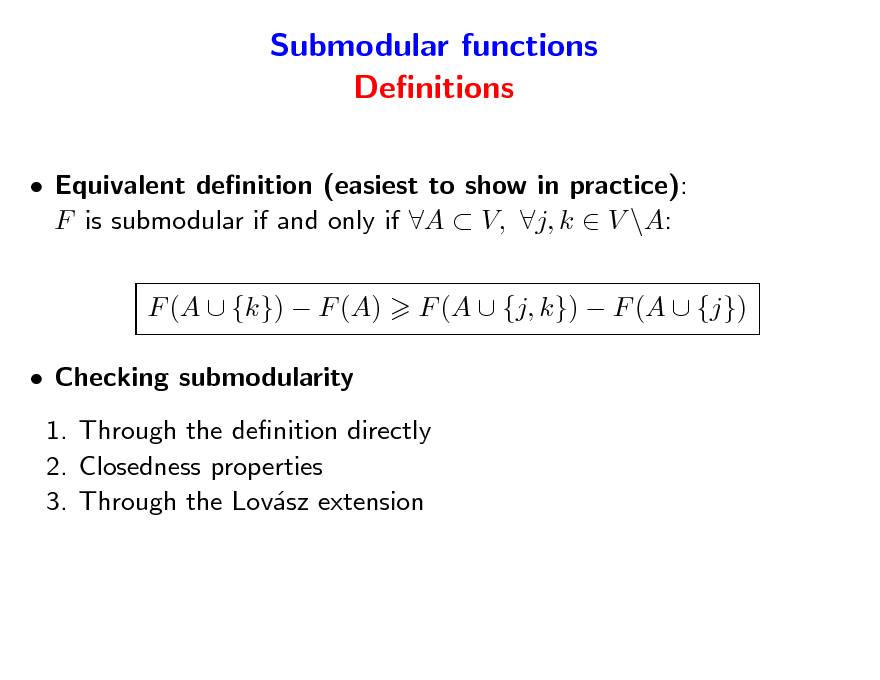

Submodular functions Denitions

Equivalent denition (easiest to show in practice): F is submodular if and only if A V, j, k V \A: F (A {k}) F (A) F (A {j, k}) F (A {j})

20

Submodular functions Denitions

Equivalent denition (easiest to show in practice): F is submodular if and only if A V, j, k V \A: F (A {k}) F (A) Checking submodularity 1. Through the denition directly 2. Closedness properties 3. Through the Lovsz extension a F (A {j, k}) F (A {j})

21

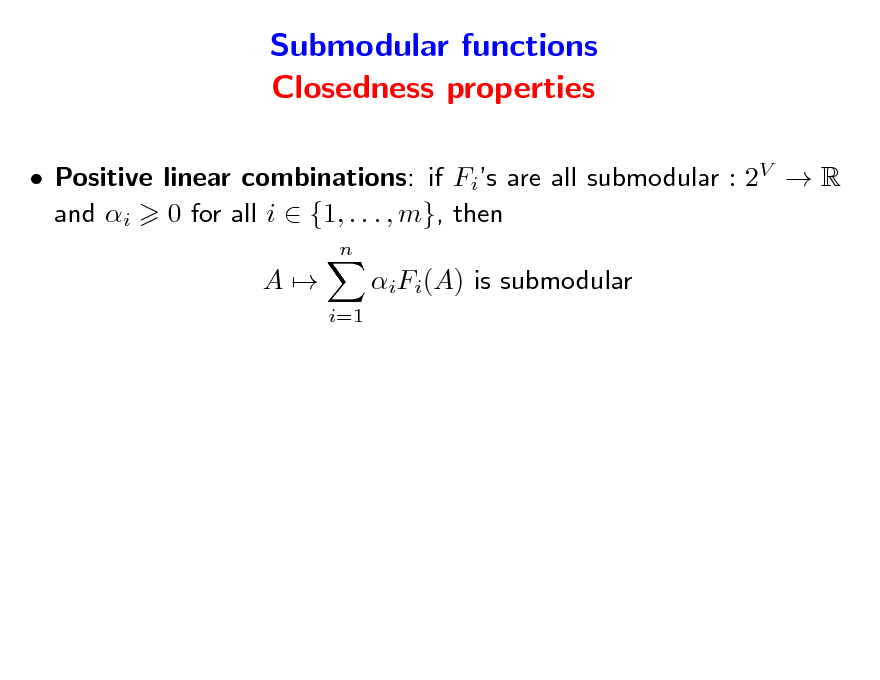

Submodular functions Closedness properties

Positive linear combinations: if Fis are all submodular : 2V R and i 0 for all i {1, . . . , m}, then

n

A

iFi(A) is submodular

i=1

22

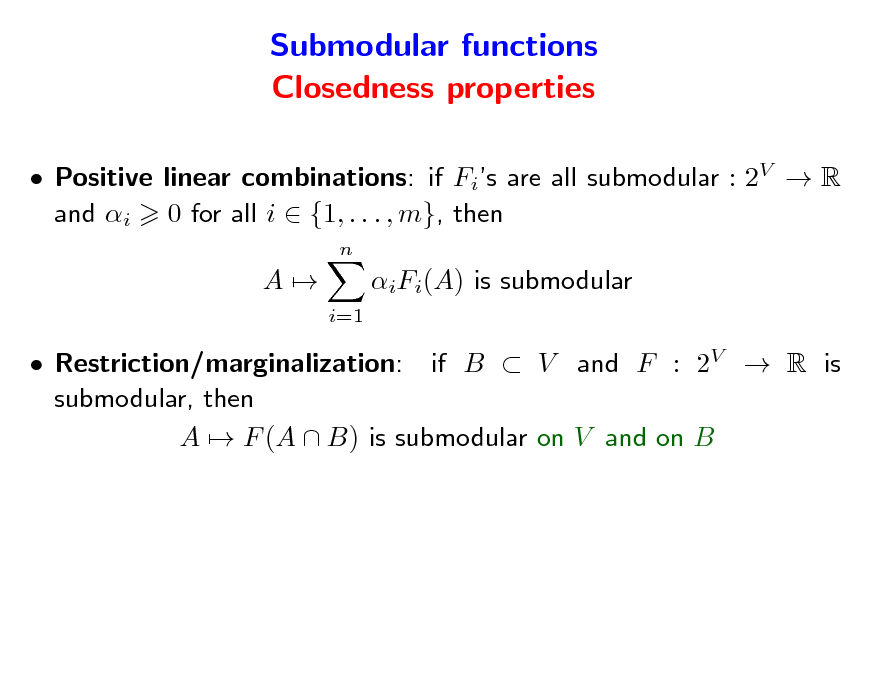

Submodular functions Closedness properties

Positive linear combinations: if Fis are all submodular : 2V R and i 0 for all i {1, . . . , m}, then

n

A

iFi(A) is submodular

i=1

Restriction/marginalization: if B V and F : 2V R is submodular, then A F (A B) is submodular on V and on B

23

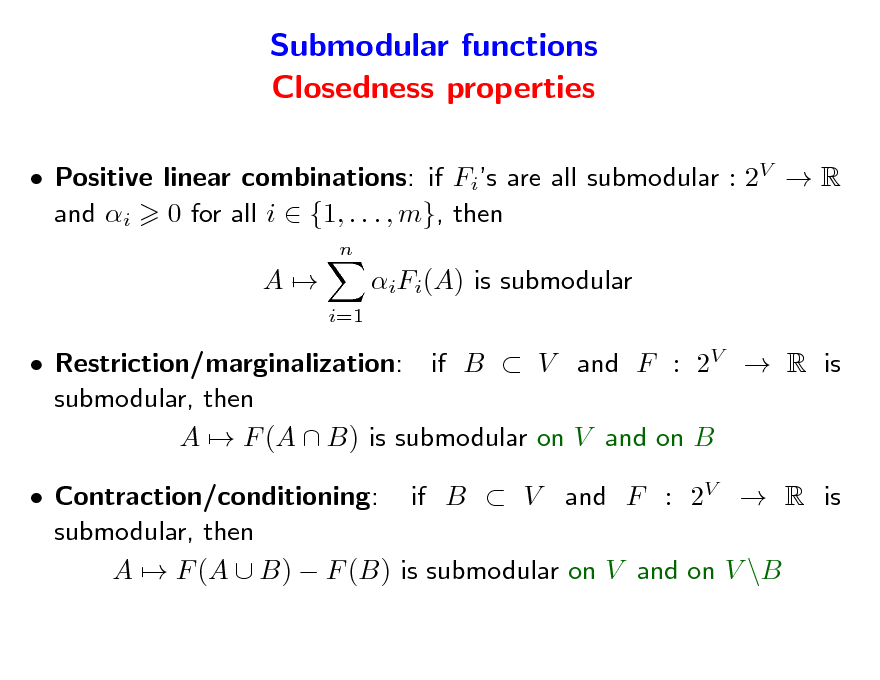

Submodular functions Closedness properties

Positive linear combinations: if Fis are all submodular : 2V R and i 0 for all i {1, . . . , m}, then

n

A

iFi(A) is submodular

i=1

Restriction/marginalization: if B V and F : 2V R is submodular, then A F (A B) is submodular on V and on B Contraction/conditioning: if B V and F : 2V R is submodular, then A F (A B) F (B) is submodular on V and on V \B

24

Submodular functions Partial minimization

Let G be a submodular function on V W , where V W = For A V , dene F (A) = minBW G(A B) minBW G(B) Property: the function F is submodular and F () = 0

25

Submodular functions Partial minimization

Let G be a submodular function on V W , where V W = For A V , dene F (A) = minBW G(A B) minBW G(B) Property: the function F is submodular and F () = 0 NB: partial minimization also preserves convexity NB: A max{F (A), G(A)} and A min{F (A), G(A)} might not be submodular

26

Examples of submodular functions Cardinality-based functions

Notation for modular function: s(A) = If s = 1V , then s(A) = |A| (cardinality) Proposition 1: If s Rp and g : R+ R is a concave function, + then F : A g(s(A)) is submodular Proposition 2: If F : A g(s(A)) is submodular for all s Rp , + then g is concave Classical example: F (A) = 1 if |A| > 0 and 0 otherwise May be rewritten as F (A) = maxkV (1A)k sk for s Rp kA

27

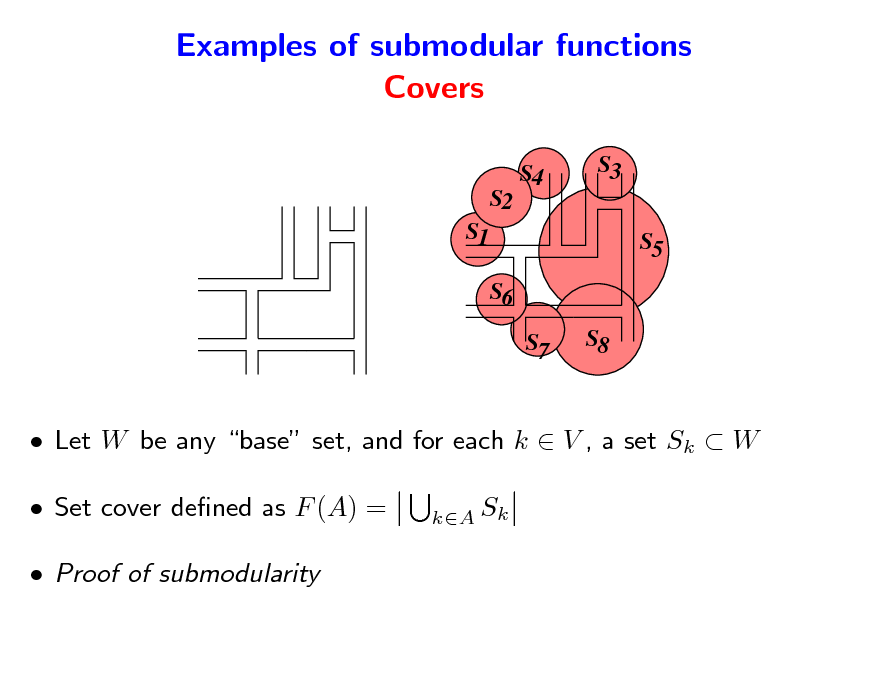

Examples of submodular functions Covers

S4 S3 S5 S6 S7 S8

S2 S1

Let W be any base set, and for each k V , a set Sk W Set cover dened as F (A) = Proof of submodularity

kA Sk

28

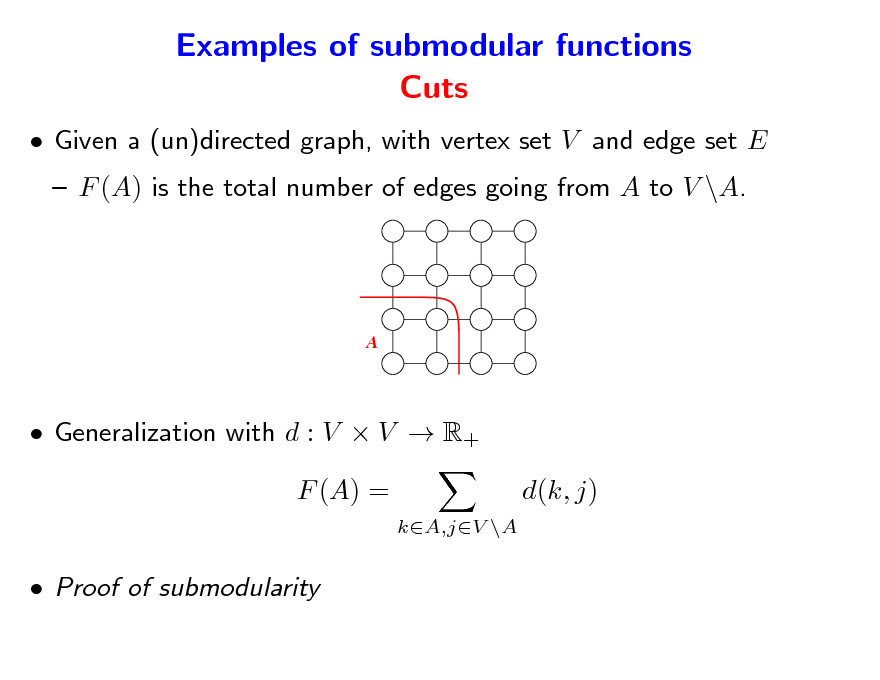

Examples of submodular functions Cuts

Given a (un)directed graph, with vertex set V and edge set E F (A) is the total number of edges going from A to V \A.

A

Generalization with d : V V R+ F (A) =

kA,jV \A

d(k, j)

Proof of submodularity

29

Examples of submodular functions Entropies

Given p random variables X1, . . . , Xp with nite number of values Dene F (A) as the joint entropy of the variables (Xk )kA F is submodular Proof of submodularity using data processing inequality (Cover and Thomas, 1991): if A B and k B, / F (A{k})F (A) = H(XA, Xk )H(XA) = H(Xk |XA) H(Xk |XB )

Symmetrized version G(A) = F (A) + F (V \A) F (V ) is mutual information between XA and XV \A Extension to continuous random variables, e.g., Gaussian: F (A) = log det AA, for some positive denite matrix Rpp

30

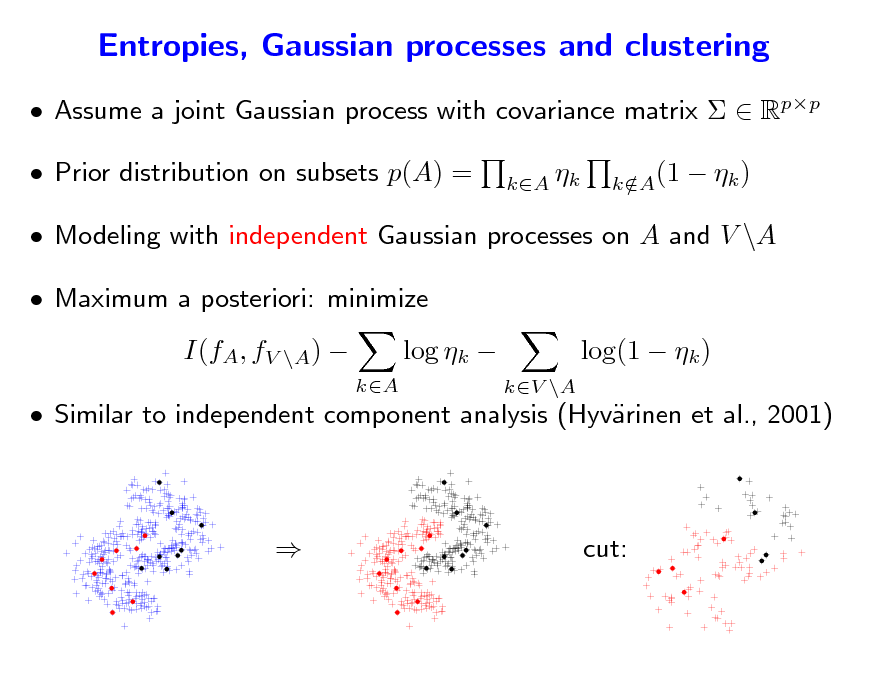

Entropies, Gaussian processes and clustering

Assume a joint Gaussian process with covariance matrix Rpp Prior distribution on subsets p(A) =

kA k kA(1 /

k )

Modeling with independent Gaussian processes on A and V \A Maximum a posteriori: minimize I(fA, fV \A)

kA

log k

Similar to independent component analysis (Hyvrinen et al., 2001) a

kV \A

log(1 k )

cut:

31

Examples of submodular functions Flows

Net-ows from multi-sink multi-source networks (Megiddo, 1974) See details in www.di.ens.fr/~ fbach/submodular_fot.pdf Ecient formulation for set covers

32

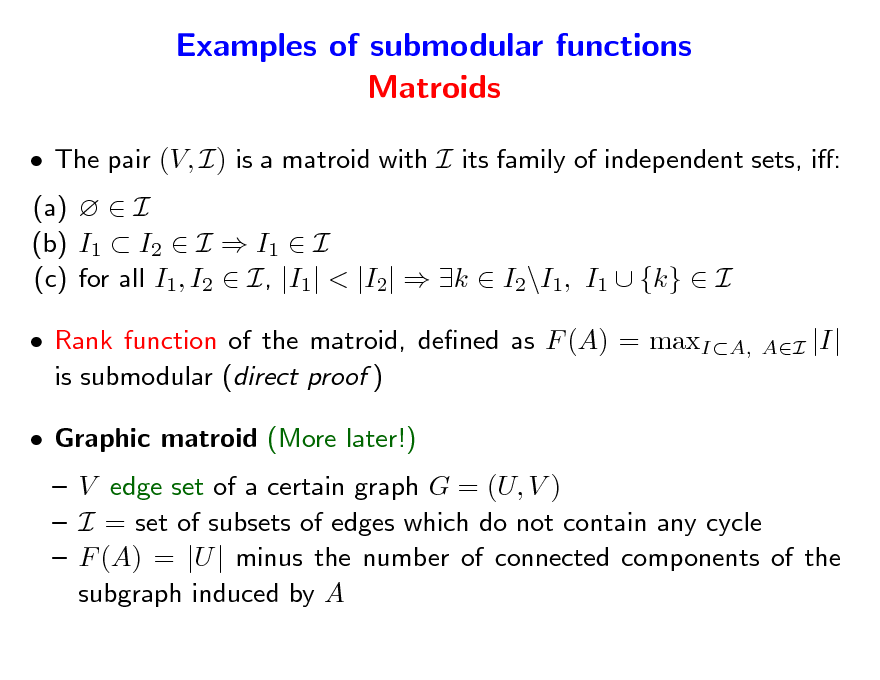

Examples of submodular functions Matroids

The pair (V, I) is a matroid with I its family of independent sets, i: (a) I (b) I1 I2 I I1 I (c) for all I1, I2 I, |I1| < |I2| k I2\I1, I1 {k} I Rank function of the matroid, dened as F (A) = maxIA, is submodular (direct proof ) Graphic matroid (More later!) V edge set of a certain graph G = (U, V ) I = set of subsets of edges which do not contain any cycle F (A) = |U | minus the number of connected components of the subgraph induced by A

AI

|I|

33

Outline

1. Submodular functions Denitions Examples of submodular functions Links with convexity through Lovsz extension a 2. Submodular optimization Minimization Links with convex optimization Maximization 3. Structured sparsity-inducing norms Norms with overlapping groups Relaxation of the penalization of supports by submodular functions

34

![Slide: Choquet integral - Lovsz extension a

Subsets may be identied with elements of {0, 1}p Given any set-function F and w such that wj1

p

wjp , dene:

f (w) =

k=1 p1

wjk [F ({j1, . . . , jk }) F ({j1, . . . , jk1})]

=

k=1

(wjk wjk+1 )F ({j1, . . . , jk }) + wjp F ({j1, . . . , jp})

(1, 0, 1)~{1, 3} (1, 1, 1)~{1, 2, 3} (0, 1, 1)~{2, 3} (1, 1, 0)~{1, 2}

(0, 0, 1)~{3} (1, 0, 0)~{1}

(0, 0, 0)~{ }

(0, 1, 0)~{2}](https://yosinski.com/mlss12/media/slides/MLSS-2012-Bach-Learning-with-Submodular-Functions_035.png)

Choquet integral - Lovsz extension a

Subsets may be identied with elements of {0, 1}p Given any set-function F and w such that wj1

p

wjp , dene:

f (w) =

k=1 p1

wjk [F ({j1, . . . , jk }) F ({j1, . . . , jk1})]

=

k=1

(wjk wjk+1 )F ({j1, . . . , jk }) + wjp F ({j1, . . . , jp})

(1, 0, 1)~{1, 3} (1, 1, 1)~{1, 2, 3} (0, 1, 1)~{2, 3} (1, 1, 0)~{1, 2}

(0, 0, 1)~{3} (1, 0, 0)~{1}

(0, 0, 0)~{ }

(0, 1, 0)~{2}

35

![Slide: Choquet integral - Lovsz extension a Properties

p

f (w) =

k=1 p1

wjk [F ({j1, . . . , jk }) F ({j1, . . . , jk1})]

=

k=1

(wjk wjk+1 )F ({j1, . . . , jk }) + wjp F ({j1, . . . , jp})

For any set-function F (even not submodular) f is piecewise-linear and positively homogeneous If w = 1A, f (w) = F (A) extension from {0, 1}p to Rp](https://yosinski.com/mlss12/media/slides/MLSS-2012-Bach-Learning-with-Submodular-Functions_036.png)

Choquet integral - Lovsz extension a Properties

p

f (w) =

k=1 p1

wjk [F ({j1, . . . , jk }) F ({j1, . . . , jk1})]

=

k=1

(wjk wjk+1 )F ({j1, . . . , jk }) + wjp F ({j1, . . . , jp})

For any set-function F (even not submodular) f is piecewise-linear and positively homogeneous If w = 1A, f (w) = F (A) extension from {0, 1}p to Rp

36

![Slide: Choquet integral - Lovsz extension a Example with p = 2

If w1 If w1 w2, f (w) = F ({1})w1 + [F ({1, 2}) F ({1})]w2 w2, f (w) = F ({2})w2 + [F ({1, 2}) F ({2})]w1

w2

w2 >w1 (0,1)/F({2}) f(w)=1 0

(1,1)/F({1,2}) w1 >w2 w1 (1,0)/F({1})

(level set {w R2, f (w) = 1} is displayed in blue) NB: Compact formulation f (w) = [F ({1})+F ({2})F ({1, 2})] min{w1, w2}+F ({1})w1+F ({2})w2](https://yosinski.com/mlss12/media/slides/MLSS-2012-Bach-Learning-with-Submodular-Functions_037.png)

Choquet integral - Lovsz extension a Example with p = 2

If w1 If w1 w2, f (w) = F ({1})w1 + [F ({1, 2}) F ({1})]w2 w2, f (w) = F ({2})w2 + [F ({1, 2}) F ({2})]w1

w2

w2 >w1 (0,1)/F({2}) f(w)=1 0

(1,1)/F({1,2}) w1 >w2 w1 (1,0)/F({1})

(level set {w R2, f (w) = 1} is displayed in blue) NB: Compact formulation f (w) = [F ({1})+F ({2})F ({1, 2})] min{w1, w2}+F ({1})w1+F ({2})w2

37

Submodular functions Links with convexity

Theorem (Lovsz, 1982): F is submodular if and only if f is convex a Proof requires additional notions: Submodular and base polyhedra

38

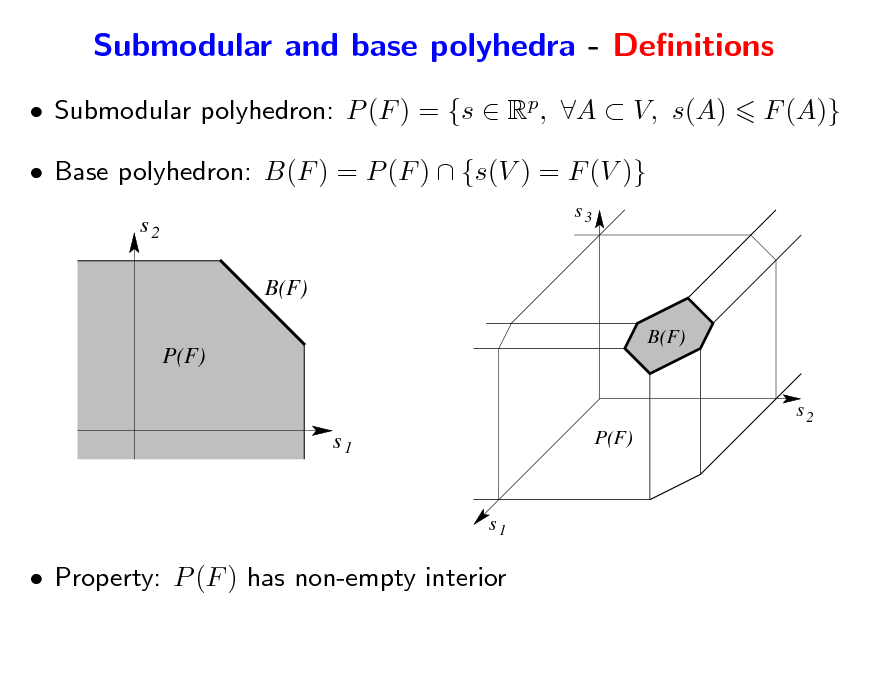

Submodular and base polyhedra - Denitions

Submodular polyhedron: P (F ) = {s Rp, A V, s(A) Base polyhedron: B(F ) = P (F ) {s(V ) = F (V )}

s2 B(F) P(F)

B(F) s3

F (A)}

s2

s1

P(F)

s1

Property: P (F ) has non-empty interior

39

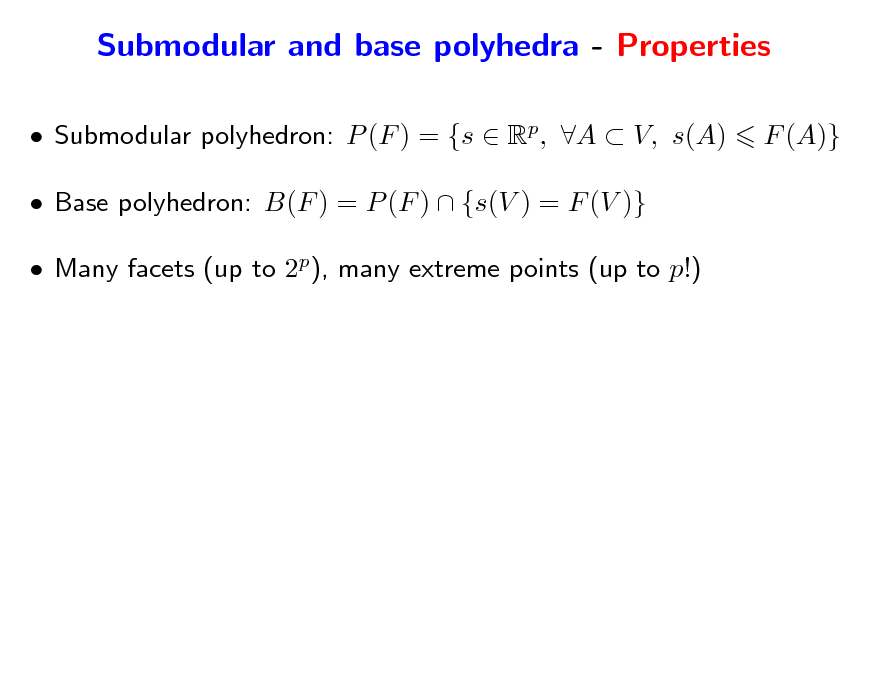

Submodular and base polyhedra - Properties

Submodular polyhedron: P (F ) = {s Rp, A V, s(A) Base polyhedron: B(F ) = P (F ) {s(V ) = F (V )} Many facets (up to 2p), many extreme points (up to p!) F (A)}

40

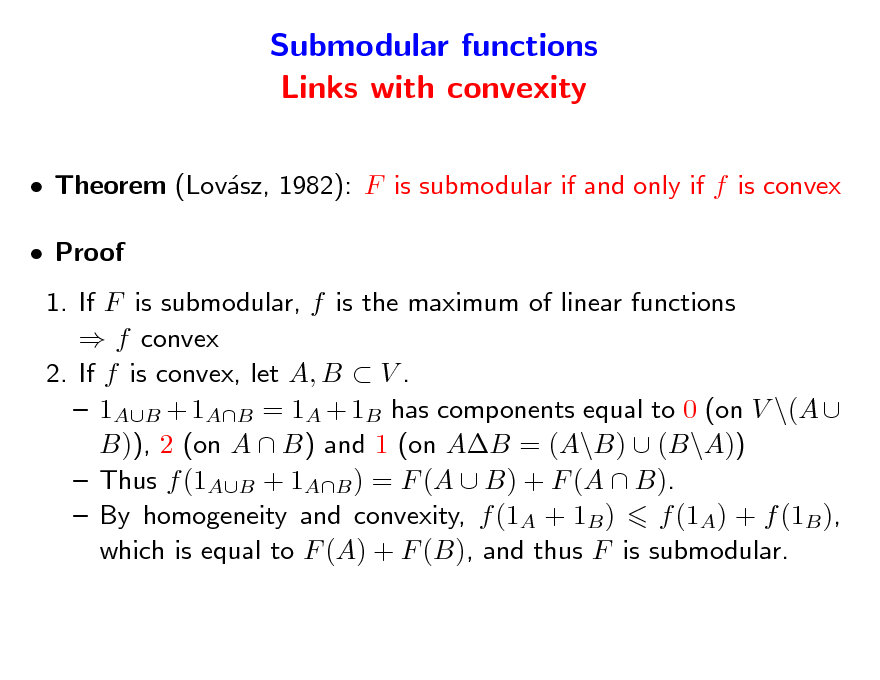

Submodular and base polyhedra - Properties

Submodular polyhedron: P (F ) = {s Rp, A V, s(A) Base polyhedron: B(F ) = P (F ) {s(V ) = F (V )} Many facets (up to 2p), many extreme points (up to p!) Fundamental property (Edmonds, 1970): If F is submodular, maximizing linear functions may be done by a greedy algorithm Let w Rp such that wj1 wjp + Let sjk = F ({j1, . . . , jk }) F ({j1, . . . , jk1}) for k {1, . . . , p} Then f (w) = max w s = max w s

sP (F ) sB(F )

F (A)}

Both problems attained at s dened above Simple proof by convex duality

41

![Slide: Greedy algorithms - Proof

Lagrange multiplier A R+ for s1A = s(A) max w s = = = min max p max p

AV

F (A)

sP (F )

A 0,AV sR

w s

AV

A[s(A) F (A)]

p

A 0,AV sR

min

AF (A) +

k=1

sk wk

A

Ak

A 0,AV

min

AV

AF (A) such that k V, wk =

A

Ak

Dene {j1,...,jk } = wjk wjk1 for k {1, . . . , p 1}, V = wjp , and zero otherwise is dual feasible and primal/dual costs are equal to f (w)](https://yosinski.com/mlss12/media/slides/MLSS-2012-Bach-Learning-with-Submodular-Functions_042.png)

Greedy algorithms - Proof

Lagrange multiplier A R+ for s1A = s(A) max w s = = = min max p max p

AV

F (A)

sP (F )

A 0,AV sR

w s

AV

A[s(A) F (A)]

p

A 0,AV sR

min

AF (A) +

k=1

sk wk

A

Ak

A 0,AV

min

AV

AF (A) such that k V, wk =

A

Ak

Dene {j1,...,jk } = wjk wjk1 for k {1, . . . , p 1}, V = wjp , and zero otherwise is dual feasible and primal/dual costs are equal to f (w)

42

![Slide: Proof of greedy algorithm - Showing primal feasibility

Assume (wlog) jk = k, and A = (u1, v1] (um, vm]

s(A) = =

m k=1 s((uk , vk ]) by modularity m k=1 F ((0, vk ]) F ((0, uk ]) by denition of s m k=1 F ((u1, vk ]) F ((u1, uk ]) by submodularity m

= F ((u1, v1 ]) + F ((u1, v1 ]) +

k=2 m k=2

F ((u1, vk ]) F ((u1, uk ]) F ((u1, v1 ] (u2, vk ]) F ((u1, v1] (u2, uk ])

by submodularity = F ((u1, v1 ] (u2, v2]) +

m k=3

F ((u1, v1] (u2, vk ]) F ((u1, v1] (u2, uk ])

By pursuing applying submodularity, we get: s(A) F ((u1, v1] (um, vm]) = F (A), i.e., s P (F )](https://yosinski.com/mlss12/media/slides/MLSS-2012-Bach-Learning-with-Submodular-Functions_043.png)

Proof of greedy algorithm - Showing primal feasibility

Assume (wlog) jk = k, and A = (u1, v1] (um, vm]

s(A) = =

m k=1 s((uk , vk ]) by modularity m k=1 F ((0, vk ]) F ((0, uk ]) by denition of s m k=1 F ((u1, vk ]) F ((u1, uk ]) by submodularity m

= F ((u1, v1 ]) + F ((u1, v1 ]) +

k=2 m k=2

F ((u1, vk ]) F ((u1, uk ]) F ((u1, v1 ] (u2, vk ]) F ((u1, v1] (u2, uk ])

by submodularity = F ((u1, v1 ] (u2, v2]) +

m k=3

F ((u1, v1] (u2, vk ]) F ((u1, v1] (u2, uk ])

By pursuing applying submodularity, we get: s(A) F ((u1, v1] (um, vm]) = F (A), i.e., s P (F )

43

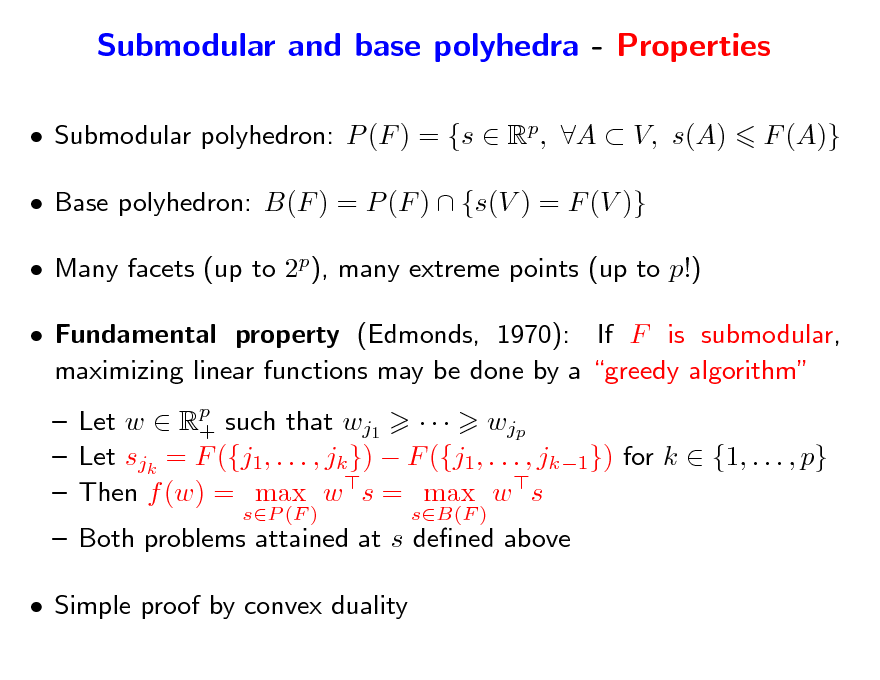

Greedy algorithm for matroids

The pair (V, I) is a matroid with I its family of independent sets, i: (a) I (b) I1 I2 I I1 I (c) for all I1, I2 I, |I1| < |I2| k I2\I1, I1 {k} I Rank function, dened as F (A) = maxIA, Greedy algorithm:

AI

|I| is submodular

Since F (A {k}) F (A) {0, 1}p, s {0, 1}p w s = k, sk =1 wk Start with A = , orders weights wk in decreasing order and sequentially add element k to A if set A remains independent

Graphic matroid: Kruskals algorithm for max. weight spanning tree!

44

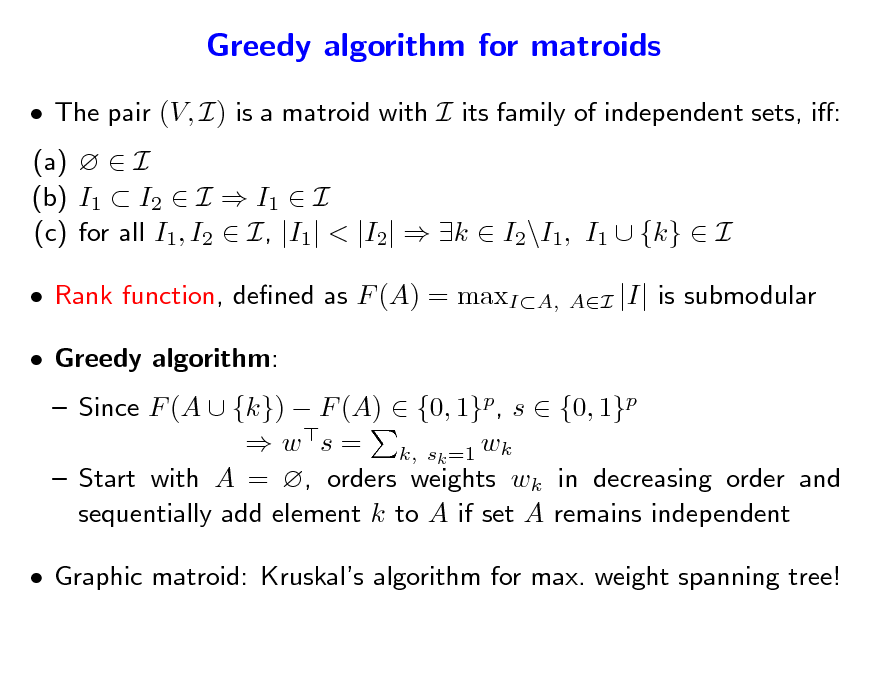

Submodular functions Links with convexity

Theorem (Lovsz, 1982): F is submodular if and only if f is convex a Proof 1. If F is submodular, f is the maximum of linear functions f convex 2. If f is convex, let A, B V . 1AB + 1AB = 1A + 1B has components equal to 0 (on V \(A B)), 2 (on A B) and 1 (on AB = (A\B) (B\A)) Thus f (1AB + 1AB ) = F (A B) + F (A B). By homogeneity and convexity, f (1A + 1B ) f (1A) + f (1B ), which is equal to F (A) + F (B), and thus F is submodular.

45

![Slide: Submodular functions Links with convexity

Theorem (Lovsz, 1982): If F is submodular, then a

AV

min F (A) =

w{0,1}p

min

f (w) = min p f (w)

w[0,1]

Proof

1. Since f is an extension of F , minAV F (A) = minw{0,1}p f (w) minw[0,1]p f (w) m 2. Any w [0, 1]p may be decomposed as w = i=1 i1Bi where B1 Bm = V , where 0 and (V ) 1: m m Then f (w) = iF (Bi) i=1 i=1 i minAV F (A) minAV F (A) (because minAV F (A) 0). Thus minw[0,1]p f (w) minAV F (A)](https://yosinski.com/mlss12/media/slides/MLSS-2012-Bach-Learning-with-Submodular-Functions_046.png)

Submodular functions Links with convexity

Theorem (Lovsz, 1982): If F is submodular, then a

AV

min F (A) =

w{0,1}p

min

f (w) = min p f (w)

w[0,1]

Proof

1. Since f is an extension of F , minAV F (A) = minw{0,1}p f (w) minw[0,1]p f (w) m 2. Any w [0, 1]p may be decomposed as w = i=1 i1Bi where B1 Bm = V , where 0 and (V ) 1: m m Then f (w) = iF (Bi) i=1 i=1 i minAV F (A) minAV F (A) (because minAV F (A) 0). Thus minw[0,1]p f (w) minAV F (A)

46

![Slide: Submodular functions Links with convexity

Theorem (Lovsz, 1982): If F is submodular, then a

AV

min F (A) =

w{0,1}p

min

f (w) = min p f (w)

w[0,1]

Consequence: Submodular function minimization may be done in polynomial time Ellipsoid algorithm: polynomial time but slow in practice](https://yosinski.com/mlss12/media/slides/MLSS-2012-Bach-Learning-with-Submodular-Functions_047.png)

Submodular functions Links with convexity

Theorem (Lovsz, 1982): If F is submodular, then a

AV

min F (A) =

w{0,1}p

min

f (w) = min p f (w)

w[0,1]

Consequence: Submodular function minimization may be done in polynomial time Ellipsoid algorithm: polynomial time but slow in practice

47

Submodular functions - Optimization

Submodular function minimization in O(p6) Schrijver (2000); Iwata et al. (2001); Orlin (2009) Ecient active set algorithm with no complexity bound Based on the ecient computability of the support function Fujishige and Isotani (2011); Wolfe (1976) Special cases with faster algorithms: cuts, ows Active area of research Machine learning: Stobbe and Krause (2010), Jegelka, Lin, and Bilmes (2011) Combinatorial optimization: see Satoru Iwatas talk Convex optimization: See next part of tutorial

48

Submodular functions - Summary

F : 2V R is submodular if and only if k V, A, B V, F (A) + F (B) A F (A {k}) F (A) is non-increasing F (A B) + F (A B)

49

Submodular functions - Summary

F : 2V R is submodular if and only if k V, A, B V, F (A) + F (B) A F (A {k}) F (A) is non-increasing F (A B) + F (A B)

Intuition 1: dened like concave functions (diminishing returns) Example: F : A g(Card(A)) is submodular if g is concave

50

Submodular functions - Summary

F : 2V R is submodular if and only if k V, A, B V, F (A) + F (B) A F (A {k}) F (A) is non-increasing F (A B) + F (A B)

Intuition 1: dened like concave functions (diminishing returns) Example: F : A g(Card(A)) is submodular if g is concave Intuition 2: behave like convex functions Polynomial-time minimization, conjugacy theory

51

Submodular functions - Examples

Concave functions of the cardinality: g(|A|) Cuts Entropies H((Xk )kA) from p random variables X1, . . . , Xp Gaussian variables H((Xk )kA) log det AA Functions of eigenvalues of sub-matrices Network ows Ecient representation for set covers Rank functions of matroids

52

![Slide: Submodular functions - Lovsz extension a

Given any set-function F and w such that wj1

p

wjp , dene:

f (w) =

k=1 p1

wjk [F ({j1, . . . , jk }) F ({j1, . . . , jk1})]

=

k=1

(wjk wjk+1 )F ({j1, . . . , jk }) + wjp F ({j1, . . . , jp})

If w = 1A, f (w) = F (A) extension from {0, 1}p to Rp (subsets may be identied with elements of {0, 1}p) f is piecewise ane and positively homogeneous F is submodular if and only if f is convex Minimizing f (w) on w [0, 1]p equivalent to minimizing F on 2V](https://yosinski.com/mlss12/media/slides/MLSS-2012-Bach-Learning-with-Submodular-Functions_053.png)

Submodular functions - Lovsz extension a

Given any set-function F and w such that wj1

p

wjp , dene:

f (w) =

k=1 p1

wjk [F ({j1, . . . , jk }) F ({j1, . . . , jk1})]

=

k=1

(wjk wjk+1 )F ({j1, . . . , jk }) + wjp F ({j1, . . . , jp})

If w = 1A, f (w) = F (A) extension from {0, 1}p to Rp (subsets may be identied with elements of {0, 1}p) f is piecewise ane and positively homogeneous F is submodular if and only if f is convex Minimizing f (w) on w [0, 1]p equivalent to minimizing F on 2V

53

Submodular functions - Submodular polyhedra

Submodular polyhedron: P (F ) = {s Rp, A V, s(A) Base polyhedron: B(F ) = P (F ) {s(V ) = F (V )} Link with Lovsz extension (Edmonds, 1970; Lovsz, 1982): a a if w Rp , then max w s = f (w) +

sP (F ) sB(F )

F (A)}

if w Rp, then max w s = f (w) Maximizer obtained by greedy algorithm: Sort the components of w, as wj1 wjp Set sjk = F ({j1, . . . , jk }) F ({j1, . . . , jk1}) Other operations on submodular polyhedra (see, e.g., Bach, 2011)

54

Outline

1. Submodular functions Denitions Examples of submodular functions Links with convexity through Lovsz extension a 2. Submodular optimization Minimization Links with convex optimization Maximization 3. Structured sparsity-inducing norms Norms with overlapping groups Relaxation of the penalization of supports by submodular functions

55

Submodular optimization problems Outline

Submodular function minimization Properties of minimizers Combinatorial algorithms Approximate minimization of the Lovsz extension a Convex optimization with the Lovsz extension a Separable optimization problems Application to submodular function minimization Submodular function maximization Simple algorithms with approximate optimality guarantees

56

Submodularity (almost) everywhere Clustering

Semi-supervised clustering

Submodular function minimization

57

Submodularity (almost) everywhere Graph cuts

Submodular function minimization

58

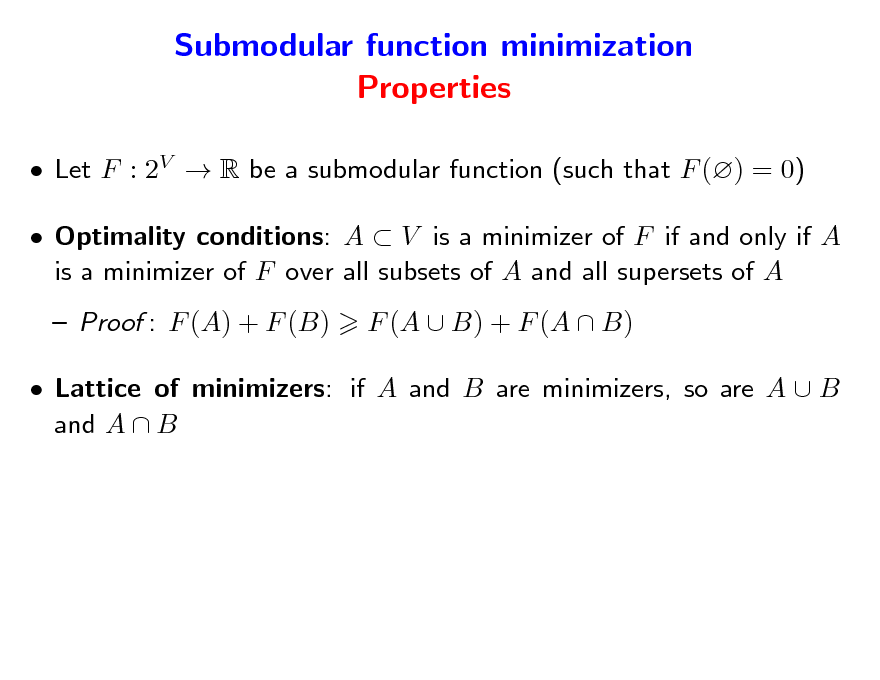

Submodular function minimization Properties

Let F : 2V R be a submodular function (such that F () = 0) Optimality conditions: A V is a minimizer of F if and only if A is a minimizer of F over all subsets of A and all supersets of A Proof : F (A) + F (B) F (A B) + F (A B)

Lattice of minimizers: if A and B are minimizers, so are A B and A B

59

![Slide: Submodular function minimization Dual problem

Let F : 2V R be a submodular function (such that F () = 0) Convex duality:

AV

min F (A) = = =

w[0,1]

min p f (w) min p max w s min p w s = max s(V )

sB(F )

w[0,1] sB(F ) sB(F ) w[0,1]

max

Optimality conditions: The pair (A, s) is optimal if and only if s B(F ) and {s < 0} A {s 0} and s(A) = F (A) Proof : F (A) s(A) = s(A {s < 0}) + s(A {s > 0}) s(A {s < 0}) s(V )](https://yosinski.com/mlss12/media/slides/MLSS-2012-Bach-Learning-with-Submodular-Functions_060.png)

Submodular function minimization Dual problem

Let F : 2V R be a submodular function (such that F () = 0) Convex duality:

AV

min F (A) = = =

w[0,1]

min p f (w) min p max w s min p w s = max s(V )

sB(F )

w[0,1] sB(F ) sB(F ) w[0,1]

max

Optimality conditions: The pair (A, s) is optimal if and only if s B(F ) and {s < 0} A {s 0} and s(A) = F (A) Proof : F (A) s(A) = s(A {s < 0}) + s(A {s > 0}) s(A {s < 0}) s(V )

60

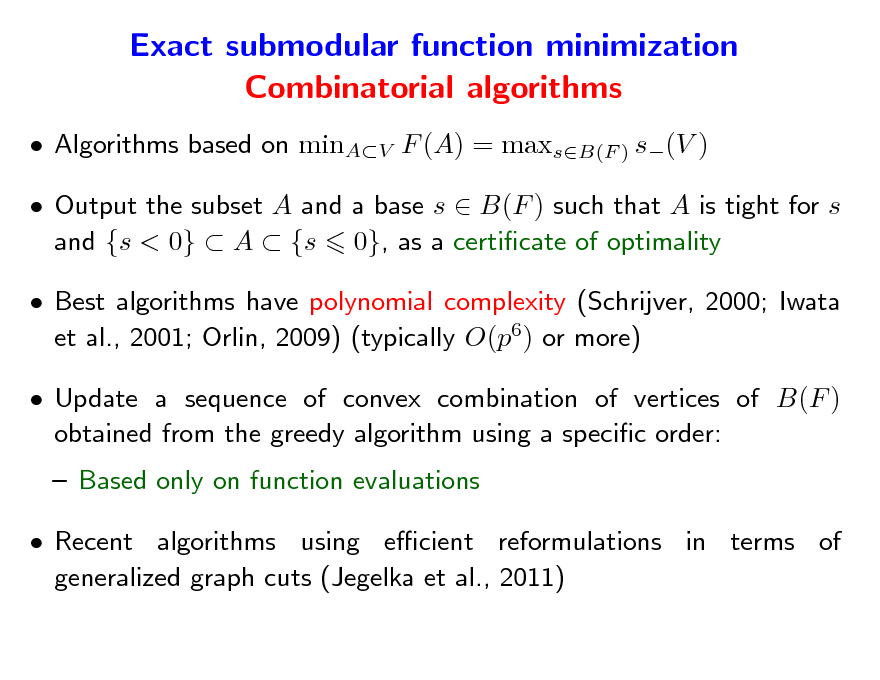

Exact submodular function minimization Combinatorial algorithms

Algorithms based on minAV F (A) = maxsB(F ) s(V ) Output the subset A and a base s B(F ) such that A is tight for s and {s < 0} A {s 0}, as a certicate of optimality Best algorithms have polynomial complexity (Schrijver, 2000; Iwata et al., 2001; Orlin, 2009) (typically O(p6) or more) Update a sequence of convex combination of vertices of B(F ) obtained from the greedy algorithm using a specic order: Based only on function evaluations Recent algorithms using ecient reformulations in terms of generalized graph cuts (Jegelka et al., 2011)

61

Exact submodular function minimization Symmetric submodular functions

A submodular function F is said symmetric if for all B V , F (V \B) = F (B) Then, by applying submodularity, A V , F (A) Example: undirected cuts, mutual information Minimization in O(p3) over all non-trivial subsets of V (Queyranne, 1998) NB: extension to minimization of posimodular functions (Nagamochi and Ibaraki, 1998), i.e., of functions that satises A, B V, F (A) + F (B) F (A\B) + F (B\A). 0

62

![Slide: Approximate submodular function minimization

For most machine learning applications, no need to obtain exact minimum For convex optimization, see, e.g., Bottou and Bousquet (2008) min F (A) = min f (w) = min p f (w)

w[0,1]

AV

w{0,1}p](https://yosinski.com/mlss12/media/slides/MLSS-2012-Bach-Learning-with-Submodular-Functions_063.png)

Approximate submodular function minimization

For most machine learning applications, no need to obtain exact minimum For convex optimization, see, e.g., Bottou and Bousquet (2008) min F (A) = min f (w) = min p f (w)

w[0,1]

AV

w{0,1}p

63

![Slide: Approximate submodular function minimization

For most machine learning applications, no need to obtain exact minimum For convex optimization, see, e.g., Bottou and Bousquet (2008) min F (A) = min f (w) = min p f (w)

w[0,1]

AV

w{0,1}p

Subgradient of f (w) = max sw through the greedy algorithm

sB(F )

Using projected subgradient descent to minimize f on [0, 1]p

C Iteration: wt = [0,1]p wt1 t st where st f (wt1) C Convergence rate: f (wt)minw[0,1]p f (w) t with primal/dual guarantees (Nesterov, 2003; Bach, 2011)](https://yosinski.com/mlss12/media/slides/MLSS-2012-Bach-Learning-with-Submodular-Functions_064.png)

Approximate submodular function minimization

For most machine learning applications, no need to obtain exact minimum For convex optimization, see, e.g., Bottou and Bousquet (2008) min F (A) = min f (w) = min p f (w)

w[0,1]

AV

w{0,1}p

Subgradient of f (w) = max sw through the greedy algorithm

sB(F )

Using projected subgradient descent to minimize f on [0, 1]p

C Iteration: wt = [0,1]p wt1 t st where st f (wt1) C Convergence rate: f (wt)minw[0,1]p f (w) t with primal/dual guarantees (Nesterov, 2003; Bach, 2011)

64

![Slide: Approximate submodular function minimization Projected subgradient descent

Assume (wlog.) that k V , F ({k}) Denote D2 =

kV

0 and F (V \{k})

F (V )

F ({k}) + F (V \{k}) F (V ) D wt1 st with st argmin wt1s pt sB(F )

Iteration: wt = [0,1]p

Proposition: t iterations of subgradient descent outputs a set At (and a certicate of optimality st) such that F (At) min F (B)

BV

F (At) (st)(V )

Dp1/2 t](https://yosinski.com/mlss12/media/slides/MLSS-2012-Bach-Learning-with-Submodular-Functions_065.png)

Approximate submodular function minimization Projected subgradient descent

Assume (wlog.) that k V , F ({k}) Denote D2 =

kV

0 and F (V \{k})

F (V )

F ({k}) + F (V \{k}) F (V ) D wt1 st with st argmin wt1s pt sB(F )

Iteration: wt = [0,1]p

Proposition: t iterations of subgradient descent outputs a set At (and a certicate of optimality st) such that F (At) min F (B)

BV

F (At) (st)(V )

Dp1/2 t

65

Submodular optimization problems Outline

Submodular function minimization Properties of minimizers Combinatorial algorithms Approximate minimization of the Lovsz extension a Convex optimization with the Lovsz extension a Separable optimization problems Application to submodular function minimization Submodular function maximization Simple algorithms with approximate optimality guarantees

66

Separable optimization on base polyhedron

Optimization of convex functions of the form (w) + f (w) with f Lovsz extension of F a Structured sparsity

Regularized risk minimization penalized by the Lovsz extension a Total variation denoising - isotonic regression

67

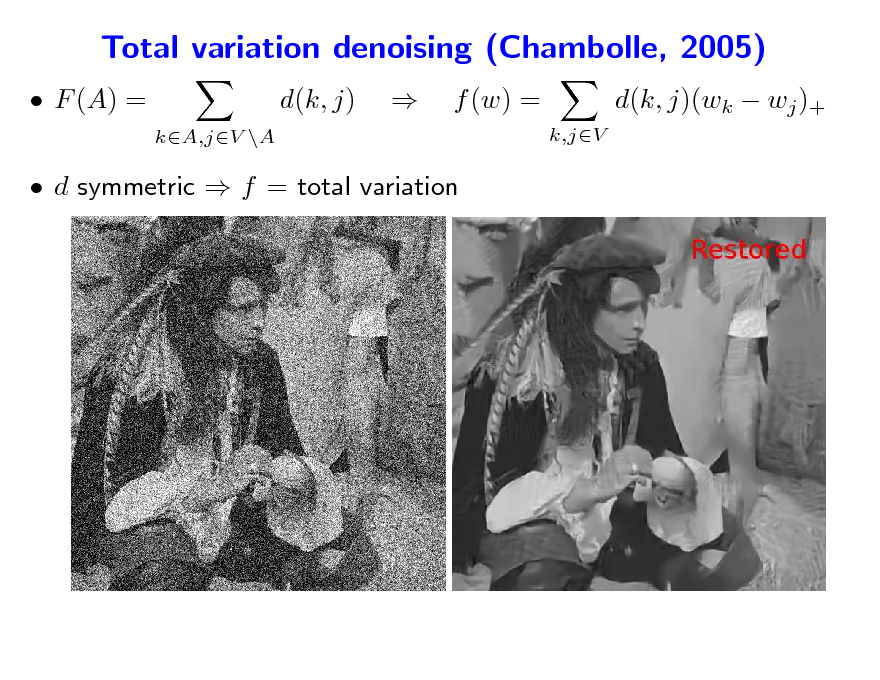

Total variation denoising (Chambolle, 2005)

F (A) = d(k, j)

kA,jV \A

f (w) =

k,jV

d(k, j)(wk wj )+

d symmetric f = total variation

68

Isotonic regression

Given real numbers xi, i = 1, . . . , p

p p

1 Find y R that minimizes (xi yi)2 such that i, yi 2 j=1 y

yi+1

x

For a directed chain, f (y) = 0 if and only if i, yi Minimize

1 2 p j=1(xi

yi+1

yi)2 + f (y) for large

69

Separable optimization on base polyhedron

Optimization of convex functions of the form (w) + f (w) with f Lovsz extension of F a Structured sparsity

Regularized risk minimization penalized by the Lovsz extension a Total variation denoising - isotonic regression

70

Separable optimization on base polyhedron

Optimization of convex functions of the form (w) + f (w) with f Lovsz extension of F a Structured sparsity

Regularized risk minimization penalized by the Lovsz extension a Total variation denoising - isotonic regression

Proximal methods (see next part of the tutorial)

Minimize (w) + f (w) for smooth as soon as the following proximal problem may be obtained eciently 1 minp w z wR 2

p 2 2

+ f (w) = minp

wR k=1

1 (wk zk )2 + f (w) 2

Submodular function minimization

71

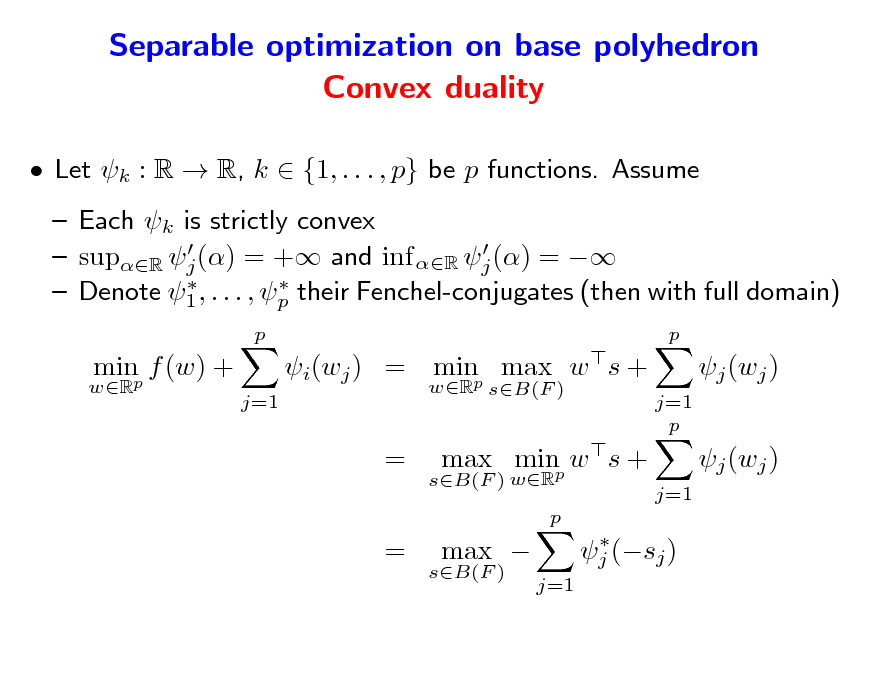

Separable optimization on base polyhedron Convex duality

Let k : R R, k {1, . . . , p} be p functions. Assume Each k is strictly convex supR j () = + and inf R j () = Denote 1 , . . . , p their Fenchel-conjugates (then with full domain)

72

Separable optimization on base polyhedron Convex duality

Let k : R R, k {1, . . . , p} be p functions. Assume Each k is strictly convex supR j () = + and inf R j () = Denote 1 , . . . , p their Fenchel-conjugates (then with full domain)

p wR p

minp f (w) +

j=1

i(wj ) = minp max w s +

wR sB(F ) j=1 p

j (wj ) j (wj )

j=1

= =

sB(F ) wR

max minp w s +

p j (sj ) j=1

sB(F )

max

73

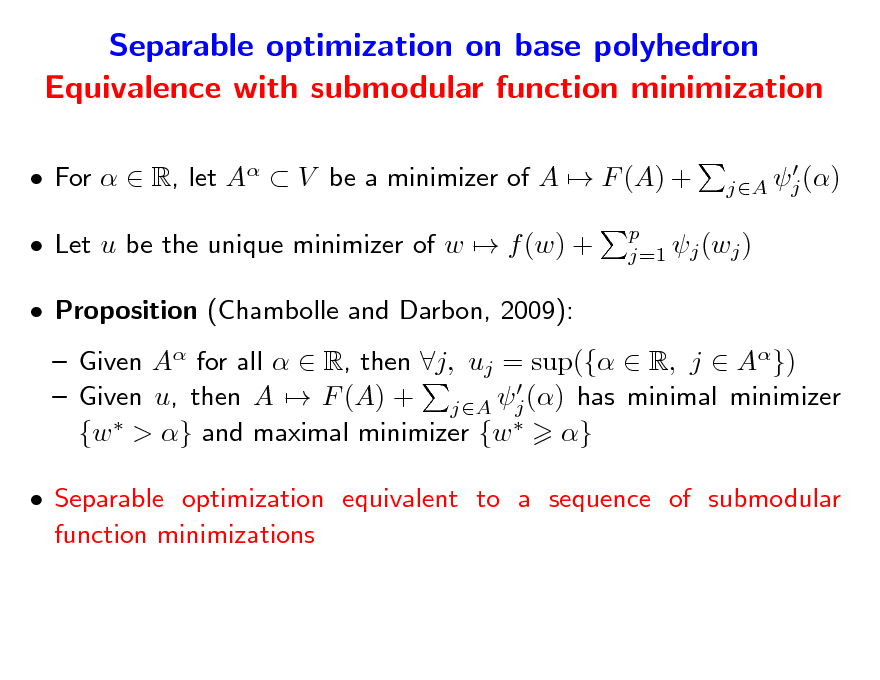

Separable optimization on base polyhedron Equivalence with submodular function minimization

For R, let A V be a minimizer of A F (A) + Let u be the unique minimizer of w f (w) + Proposition (Chambolle and Darbon, 2009): Given A for all R, then j, uj = sup({ R, j A}) Given u, then A F (A) + jA j () has minimal minimizer {w > } and maximal minimizer {w } Separable optimization equivalent to a sequence of submodular function minimizations

j () jA

p j=1 j (wj )

74

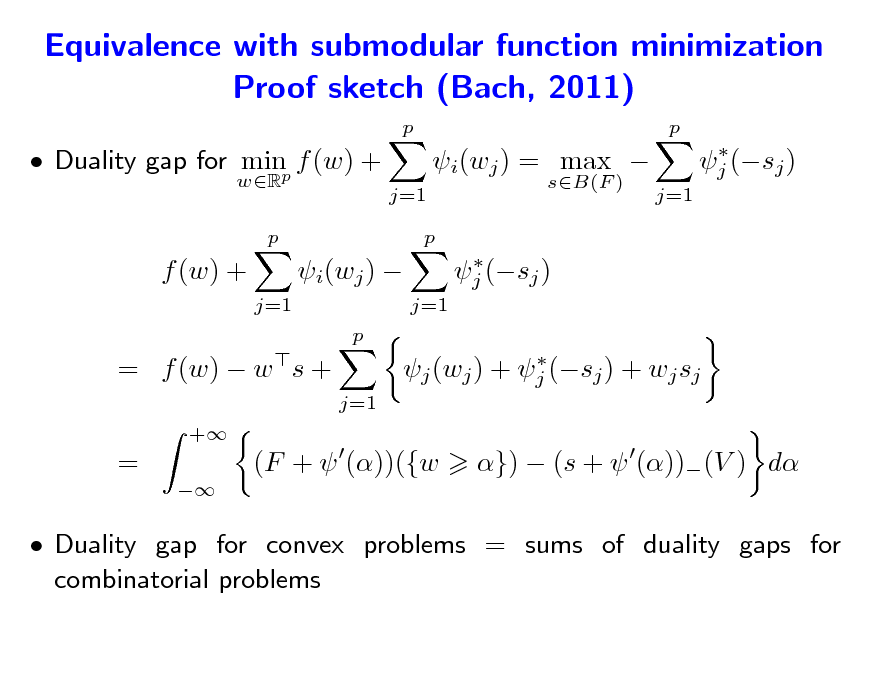

Equivalence with submodular function minimization Proof sketch (Bach, 2011)

p p

Duality gap for minp f (w) +

wR p

j=1

i(wj ) = max

sB(F ) j (sj )

j (sj ) j=1

p

f (w) +

j=1

i(wj )

p

j=1

= f (w) w s +

+

j (wj ) + j (sj ) + wj sj j=1

=

(F + ())({w

}) (s + ())(V ) d

Duality gap for convex problems = sums of duality gaps for combinatorial problems

75

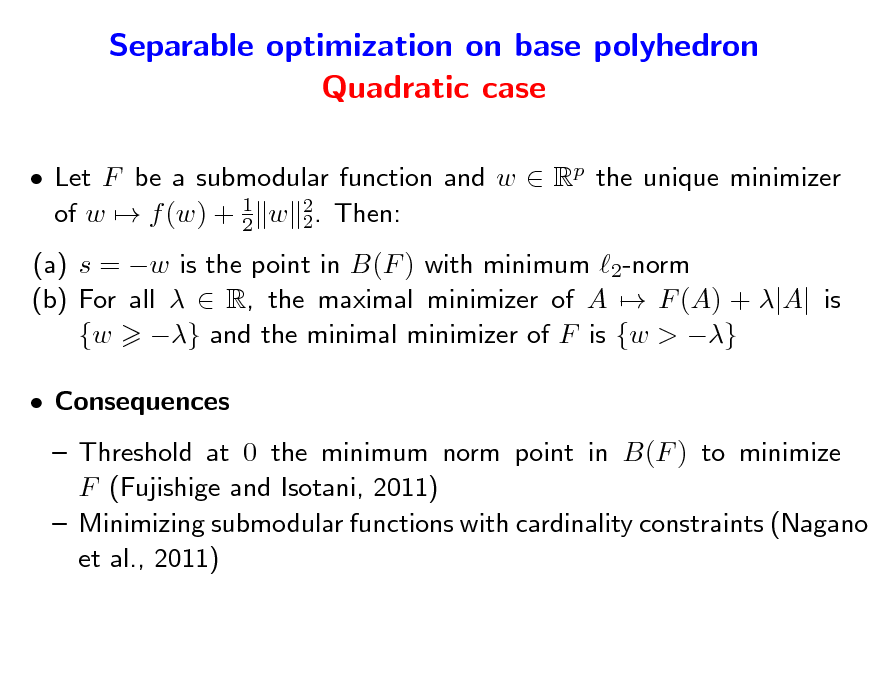

Separable optimization on base polyhedron Quadratic case

Let F be a submodular function and w Rp the unique minimizer of w f (w) + 1 w 2. Then: 2 2 (a) s = w is the point in B(F ) with minimum 2-norm (b) For all R, the maximal minimizer of A F (A) + |A| is {w } and the minimal minimizer of F is {w > } Consequences Threshold at 0 the minimum norm point in B(F ) to minimize F (Fujishige and Isotani, 2011) Minimizing submodular functions with cardinality constraints (Nagano et al., 2011)

76

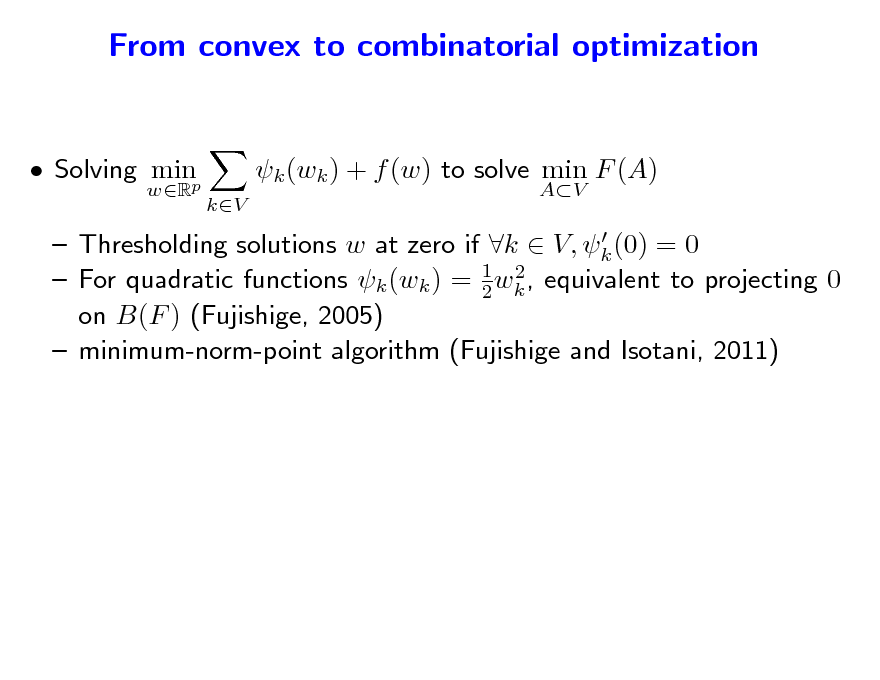

From convex to combinatorial optimization and vice-versa...

Solving minp

wR

k (wk ) + f (w) to solve min F (A)

kV AV

Thresholding solutions w at zero if k V, k (0) = 0 2 For quadratic functions k (wk ) = 1 wk , equivalent to projecting 0 2 on B(F ) (Fujishige, 2005) minimum-norm-point algorithm (Fujishige and Isotani, 2011)

77

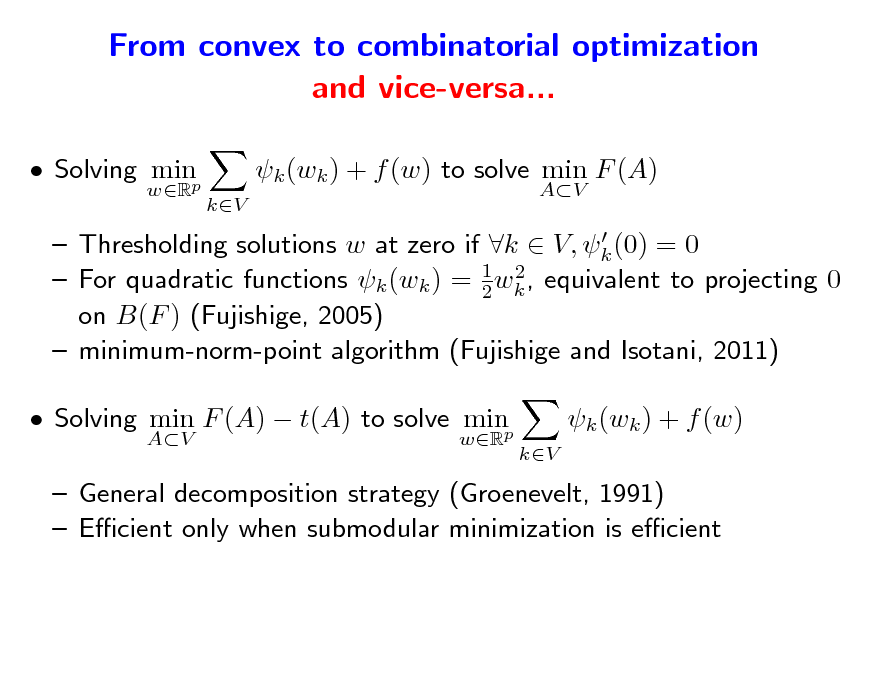

From convex to combinatorial optimization and vice-versa...

Solving minp

wR

k (wk ) + f (w) to solve min F (A)

kV AV

Thresholding solutions w at zero if k V, k (0) = 0 2 For quadratic functions k (wk ) = 1 wk , equivalent to projecting 0 2 on B(F ) (Fujishige, 2005) minimum-norm-point algorithm (Fujishige and Isotani, 2011)

Solving min F (A) t(A) to solve minp

AV wR

k (wk ) + f (w)

kV

General decomposition strategy (Groenevelt, 1991) Ecient only when submodular minimization is ecient

78

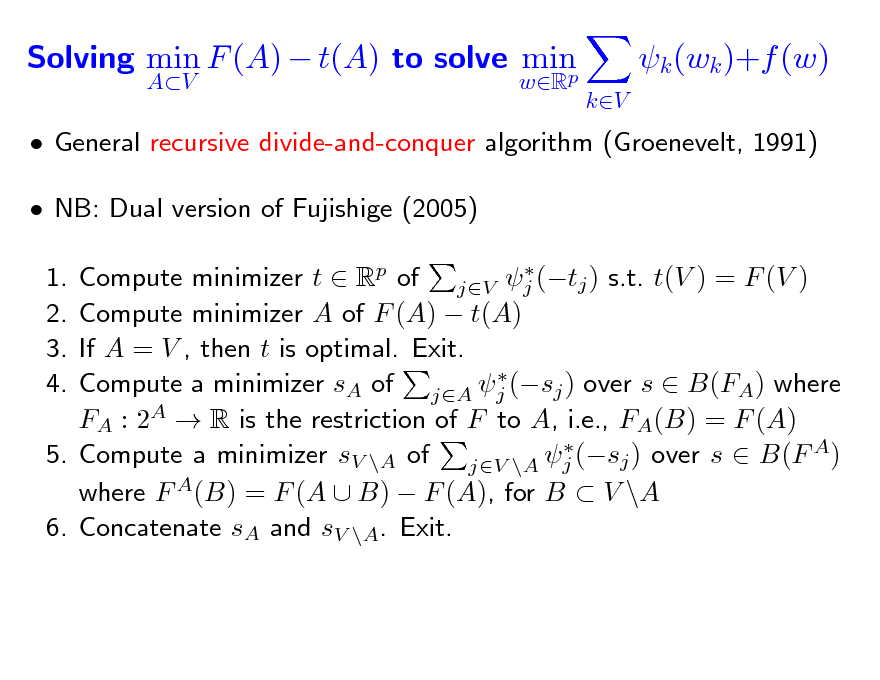

Solving min F (A) t(A) to solve min p

AV wR

k (wk )+f (w)

kV

General recursive divide-and-conquer algorithm (Groenevelt, 1991) NB: Dual version of Fujishige (2005)

Compute minimizer t Rp of jV j (tj ) s.t. t(V ) = F (V ) Compute minimizer A of F (A) t(A) If A = V , then t is optimal. Exit. Compute a minimizer sA of jA j (sj ) over s B(FA) where FA : 2A R is the restriction of F to A, i.e., FA(B) = F (A) 5. Compute a minimizer sV \A of jV \A j (sj ) over s B(F A) where F A(B) = F (A B) F (A), for B V \A 6. Concatenate sA and sV \A. Exit.

1. 2. 3. 4.

79

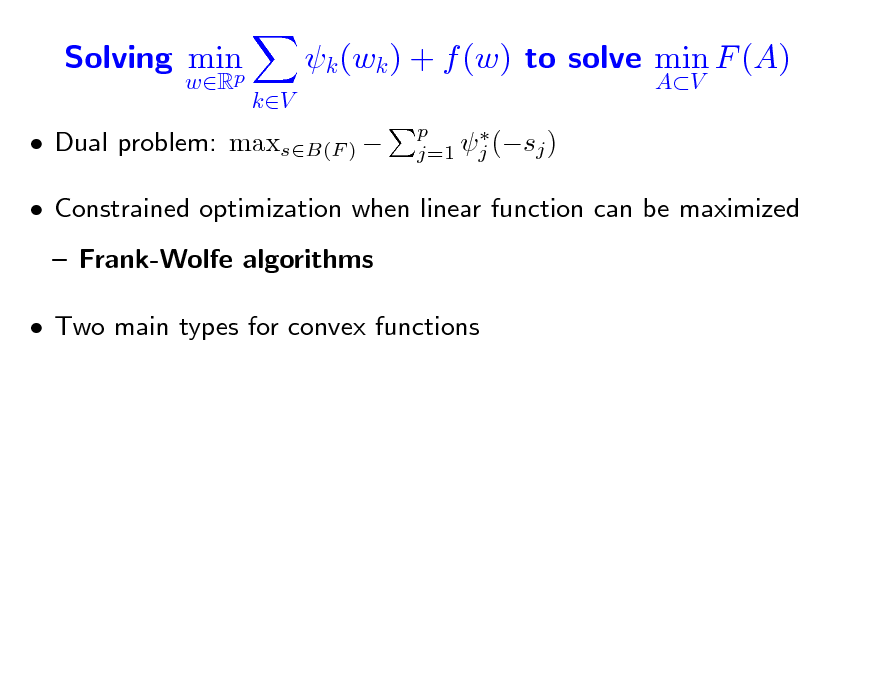

Solving min p

wR kV

k (wk ) + f (w) to solve min F (A)

AV

p j (sj ) j=1

Dual problem: maxsB(F )

Constrained optimization when linear function can be maximized Frank-Wolfe algorithms Two main types for convex functions

80

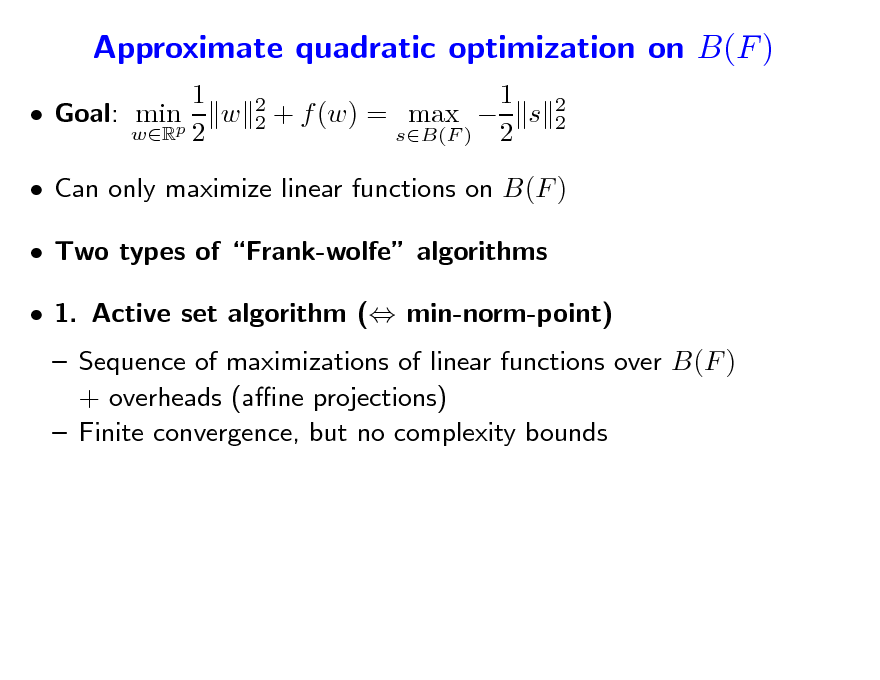

Approximate quadratic optimization on B(F )

1 Goal: minp w wR 2

2 2

1 + f (w) = max s sB(F ) 2

2 2

Can only maximize linear functions on B(F ) Two types of Frank-wolfe algorithms 1. Active set algorithm ( min-norm-point) Sequence of maximizations of linear functions over B(F ) + overheads (ane projections) Finite convergence, but no complexity bounds

81

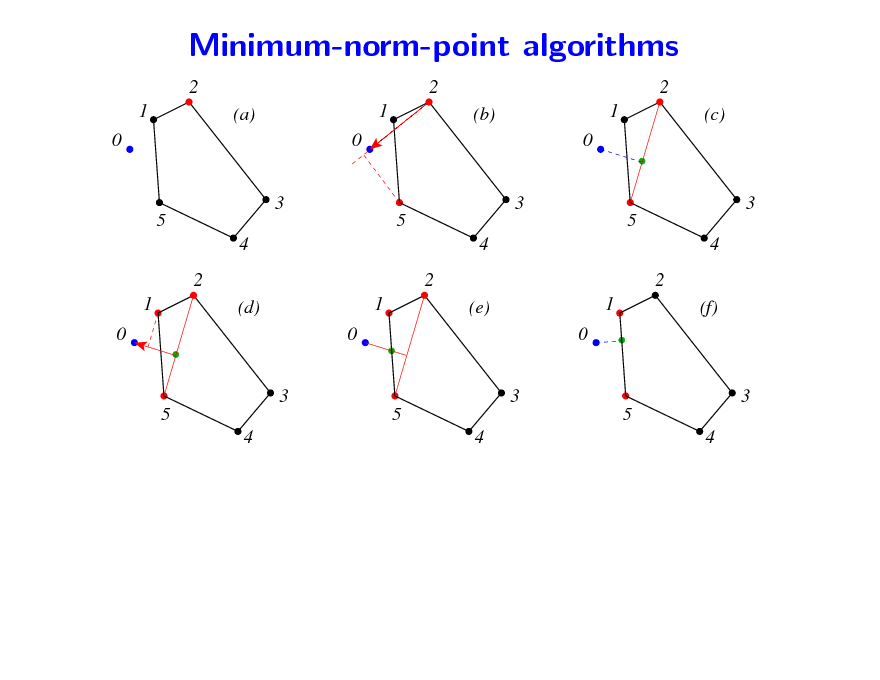

Minimum-norm-point algorithms

2 1 0 3 5 4 2 1 0 3 5 4 5 4 (d) 0 3 5 4 1 2 (e) 0 3 1 5 4 2 (f) (a) 0 3 5 4 1 2 (b) 0 3 1 2 (c)

82

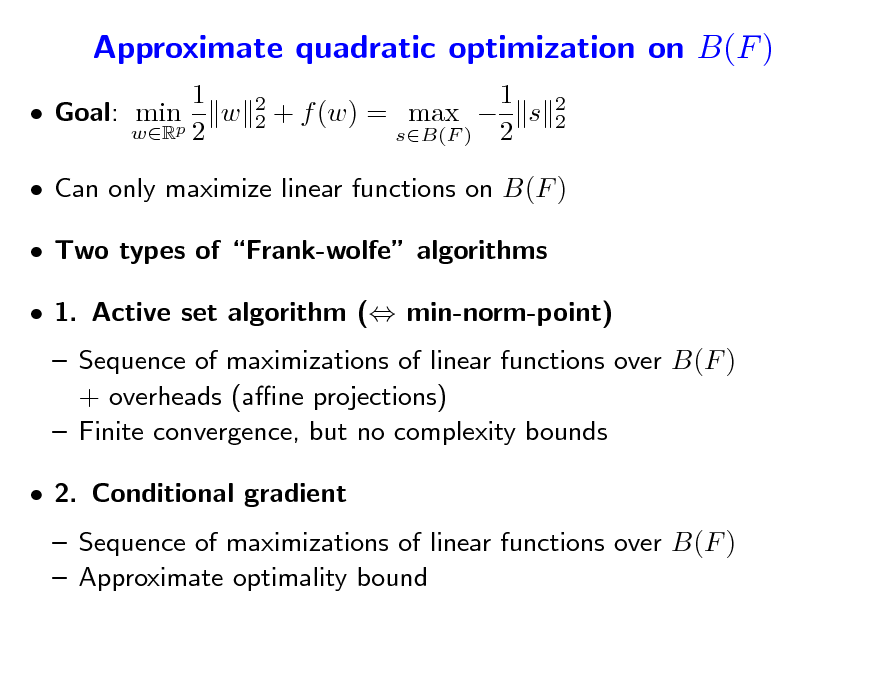

Approximate quadratic optimization on B(F )

1 Goal: minp w wR 2

2 2

1 + f (w) = max s sB(F ) 2

2 2

Can only maximize linear functions on B(F ) Two types of Frank-wolfe algorithms 1. Active set algorithm ( min-norm-point) Sequence of maximizations of linear functions over B(F ) + overheads (ane projections) Finite convergence, but no complexity bounds 2. Conditional gradient Sequence of maximizations of linear functions over B(F ) Approximate optimality bound

83

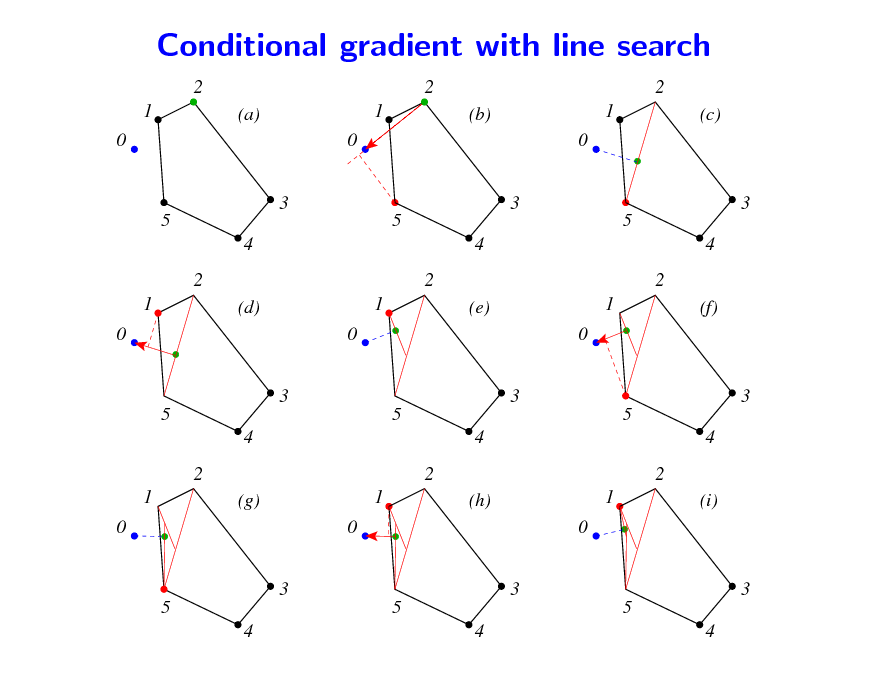

Conditional gradient with line search

2 1 0 3 5 4 2 1 0 3 5 4 2 1 0 3 5 4 5 4 (g) 0 3 5 4 1 2 (h) 0 3 1 5 4 2 (i) (d) 0 3 5 4 1 2 (e) 0 3 1 5 4 2 (f) (a) 0 3 5 4 1 2 (b) 0 3 1 2 (c)

84

Approximate quadratic optimization on B(F )

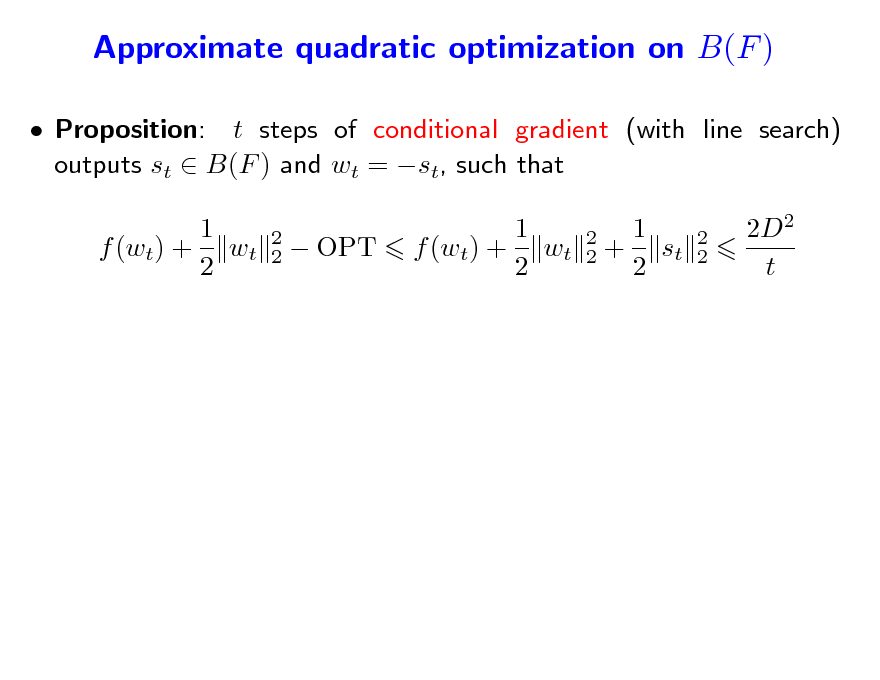

Proposition: t steps of conditional gradient (with line search) outputs st B(F ) and wt = st, such that 1 f (wt) + wt 2

2 2

OPT

1 f (wt) + wt 2

2 2

1 + st 2

2 2

2D2 t

85

Approximate quadratic optimization on B(F )

Proposition: t steps of conditional gradient (with line search) outputs st B(F ) and wt = st, such that 1 f (wt) + wt 2

2 2

OPT

1 f (wt) + wt 2

2 2

1 + st 2

2 2

2D2 t

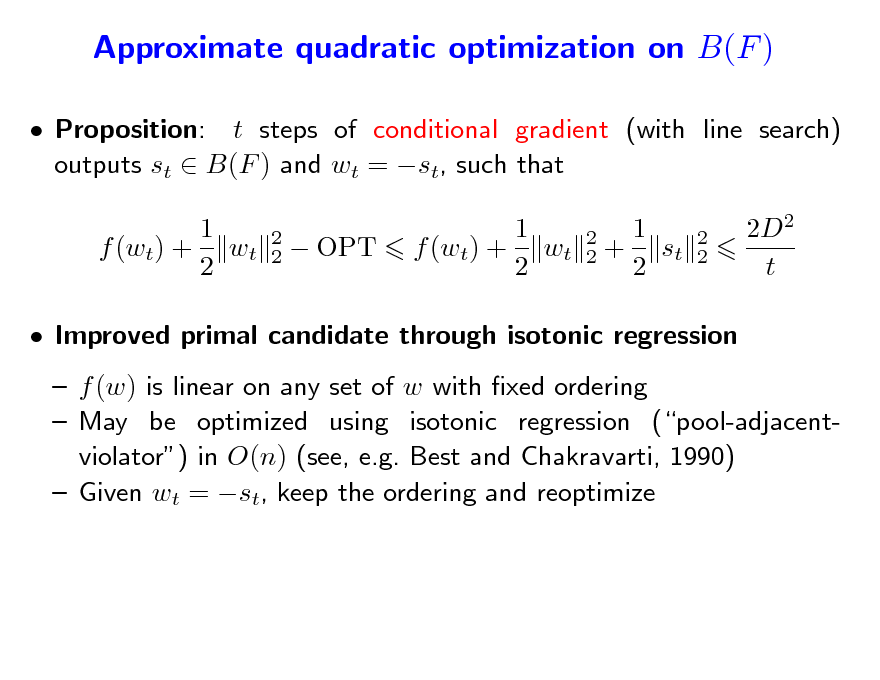

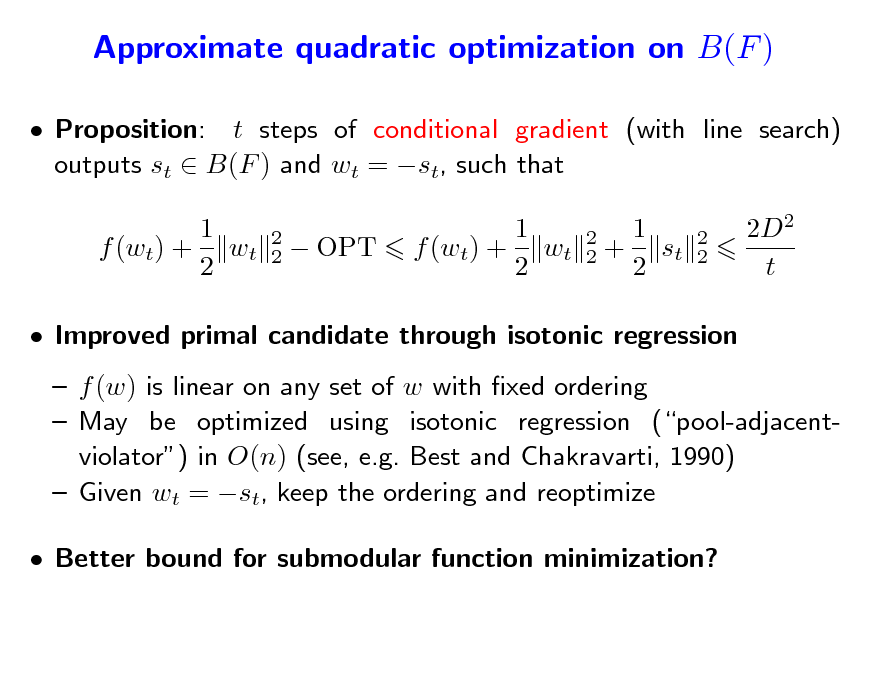

Improved primal candidate through isotonic regression f (w) is linear on any set of w with xed ordering May be optimized using isotonic regression (pool-adjacentviolator) in O(n) (see, e.g. Best and Chakravarti, 1990) Given wt = st, keep the ordering and reoptimize

86

Approximate quadratic optimization on B(F )

Proposition: t steps of conditional gradient (with line search) outputs st B(F ) and wt = st, such that 1 f (wt) + wt 2

2 2

OPT

1 f (wt) + wt 2

2 2

1 + st 2

2 2

2D2 t

Improved primal candidate through isotonic regression f (w) is linear on any set of w with xed ordering May be optimized using isotonic regression (pool-adjacentviolator) in O(n) (see, e.g. Best and Chakravarti, 1990) Given wt = st, keep the ordering and reoptimize Better bound for submodular function minimization?

87

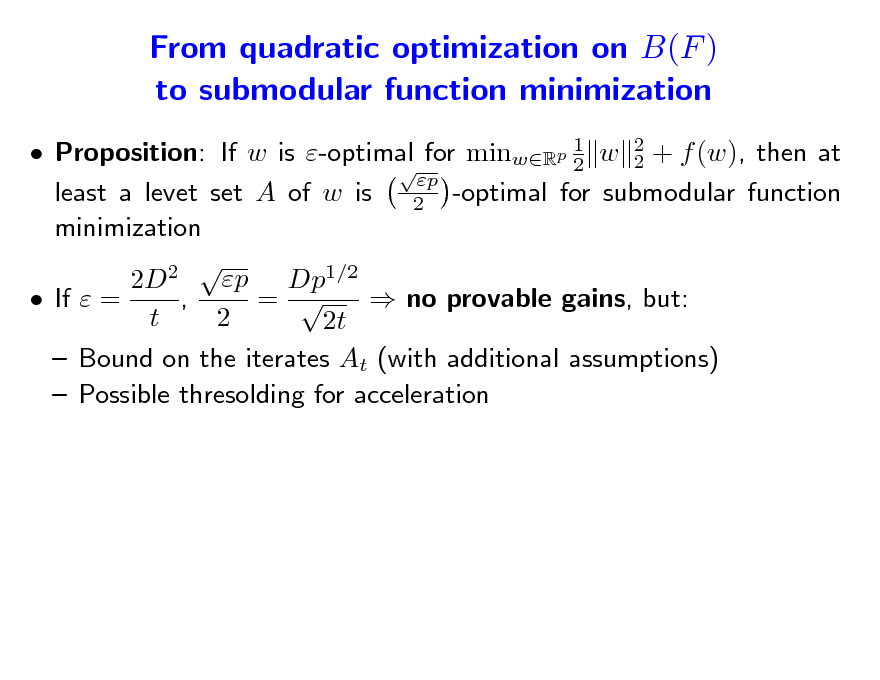

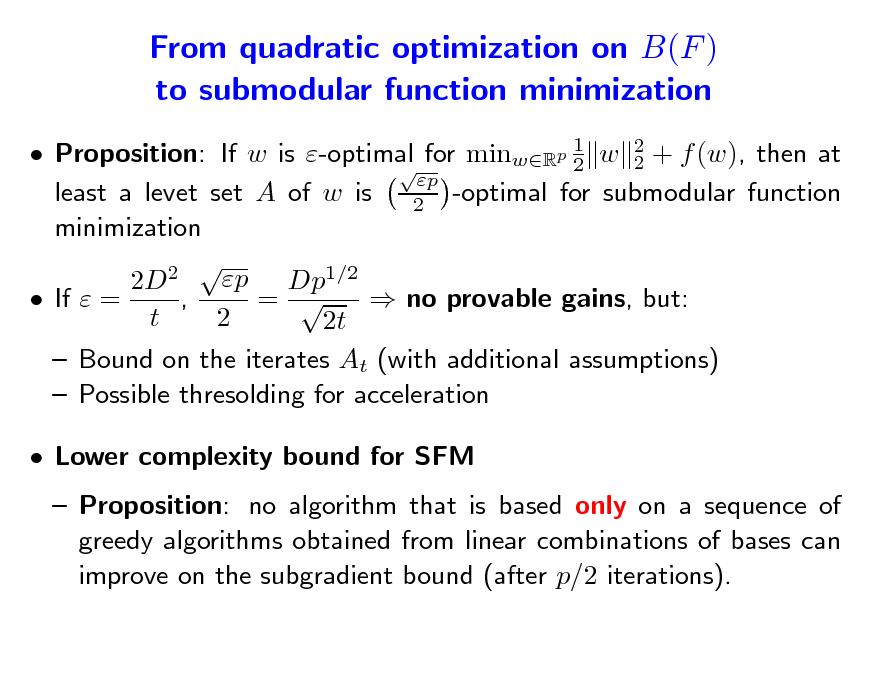

From quadratic optimization on B(F ) to submodular function minimization

Proposition: If w is -optimal for minwRp 1 w 2 + f (w), then at 2 2 p least a levet set A of w is 2 -optimal for submodular function minimization 2 p 2D Dp1/2 If = , = no provable gains, but: t 2 2t Bound on the iterates At (with additional assumptions) Possible thresolding for acceleration

88

From quadratic optimization on B(F ) to submodular function minimization

Proposition: If w is -optimal for minwRp 1 w 2 + f (w), then at 2 2 p least a levet set A of w is 2 -optimal for submodular function minimization 2 p Dp1/2 2D , = If = no provable gains, but: t 2 2t Bound on the iterates At (with additional assumptions) Possible thresolding for acceleration Lower complexity bound for SFM Proposition: no algorithm that is based only on a sequence of greedy algorithms obtained from linear combinations of bases can improve on the subgradient bound (after p/2 iterations).

89

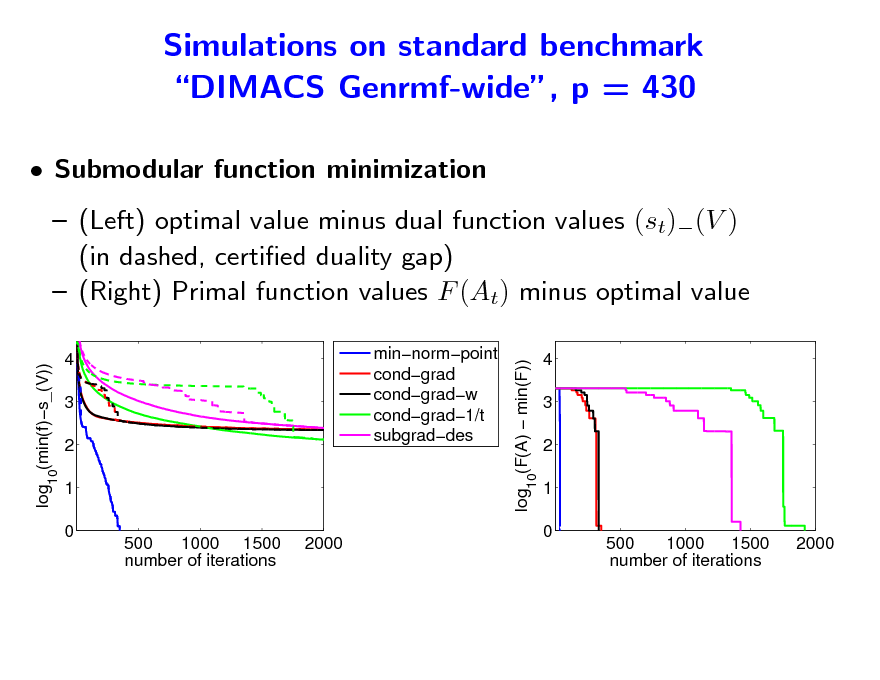

Simulations on standard benchmark DIMACS Genrmf-wide, p = 430

Submodular function minimization (Left) optimal value minus dual function values (st)(V ) (in dashed, certied duality gap) (Right) Primal function values F (At) minus optimal value

log10(F(A) min(F))

log10(min(f)s_(V)) 4 3 2 1 0 500 1000 1500 number of iterations 2000 minnormpoint condgrad condgradw condgrad1/t subgraddes

4 3 2 1 0 500 1000 1500 number of iterations 2000

90

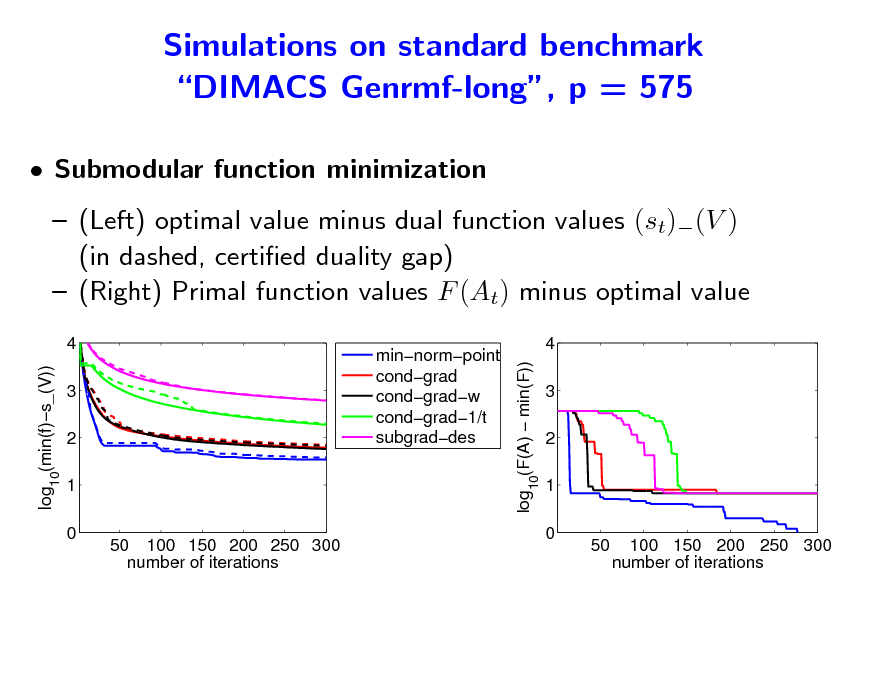

Simulations on standard benchmark DIMACS Genrmf-long, p = 575

Submodular function minimization (Left) optimal value minus dual function values (st)(V ) (in dashed, certied duality gap) (Right) Primal function values F (At) minus optimal value

4 log (min(f)s_(V)) 3 2 1 0

log (F(A) min(F))

minnormpoint condgrad condgradw condgrad1/t subgraddes

4 3 2 1 0

10

10

50 100 150 200 250 300 number of iterations

50

100 150 200 250 300 number of iterations

91

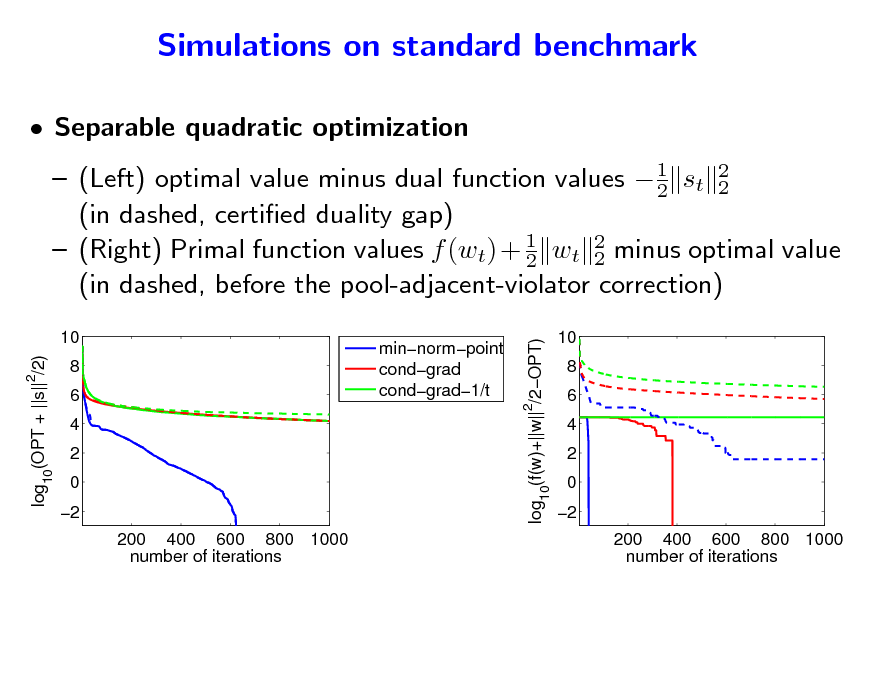

Simulations on standard benchmark

Separable quadratic optimization

1 (Left) optimal value minus dual function values 2 st 2 2 (in dashed, certied duality gap) (Right) Primal function values f (wt) + 1 wt 2 minus optimal value 2 2 (in dashed, before the pool-adjacent-violator correction)

minnormpoint condgrad condgrad1/t

log10(f(w)+||w||2/2OPT)

10 log10(OPT + ||s|| /2)

2

10 8 6 4 2 0 2 200 400 600 800 1000 number of iterations

8 6 4 2 0 2 200 400 600 800 1000 number of iterations

92

Submodularity (almost) everywhere Sensor placement

Each sensor covers a certain area (Krause and Guestrin, 2005) Goal: maximize coverage

Submodular function maximization Extension to experimental design (Seeger, 2009)

93

Submodular function maximization

Occurs in various form in applications but is NP-hard Unconstrained maximization: Feige et al. (2007) shows that that for non-negative functions, a random subset already achieves at least 1/4 of the optimal value, while local search techniques achieve at least 1/2 Maximizing non-decreasing cardinality constraint submodular functions with

Greedy algorithm achieves (1 1/e) of the optimal value Proof (Nemhauser et al., 1978)

94

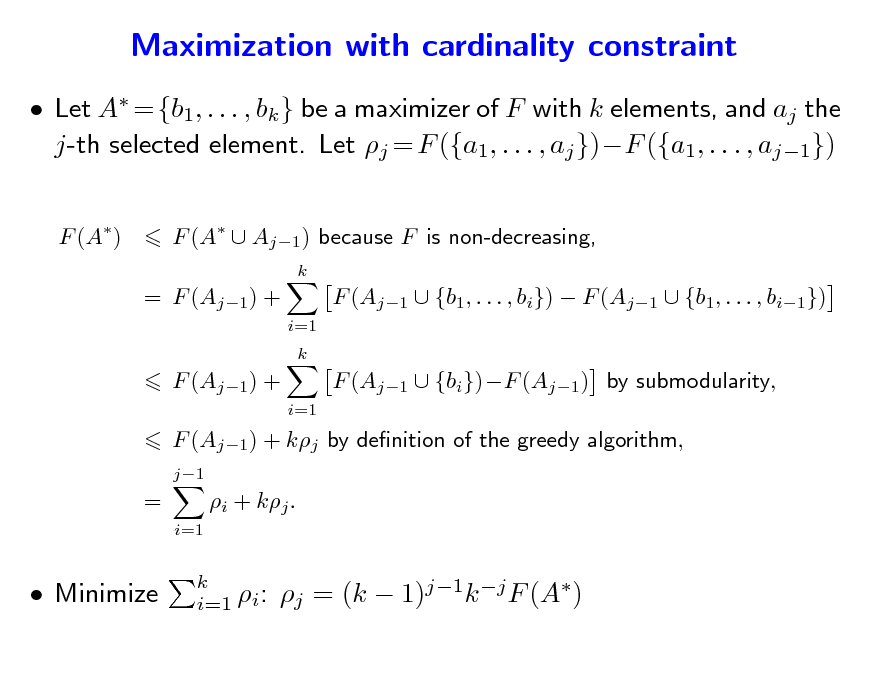

Maximization with cardinality constraint

Let A = {b1, . . . , bk } be a maximizer of F with k elements, and aj the j-th selected element. Let j = F ({a1, . . . , aj })F ({a1, . . . , aj1})

F (A) F (A Aj1 ) because F is non-decreasing,

k

= F (Aj1) +

i=1 k

F (Aj1 {b1, . . . , bi}) F (Aj1 {b1, . . . , bi1}) F (Aj1 {bi})F (Aj1) by submodularity,

F (Aj1) +

i=1

F (Aj1) + kj by denition of the greedy algorithm,

j1

=

i=1

i + kj .

Minimize

k i=1 i:

j = (k 1)j1k j F (A)

95

Submodular optimization problems Summary

Submodular function minimization Properties of minimizers Combinatorial algorithms Approximate minimization of the Lovsz extension a Convex optimization with the Lovsz extension a Separable optimization problems Application to submodular function minimization Submodular function maximization Simple algorithms with approximate optimality guarantees

96

Outline

1. Submodular functions Denitions Examples of submodular functions Links with convexity through Lovsz extension a 2. Submodular optimization Minimization Links with convex optimization Maximization 3. Structured sparsity-inducing norms Norms with overlapping groups Relaxation of the penalization of supports by submodular functions

97

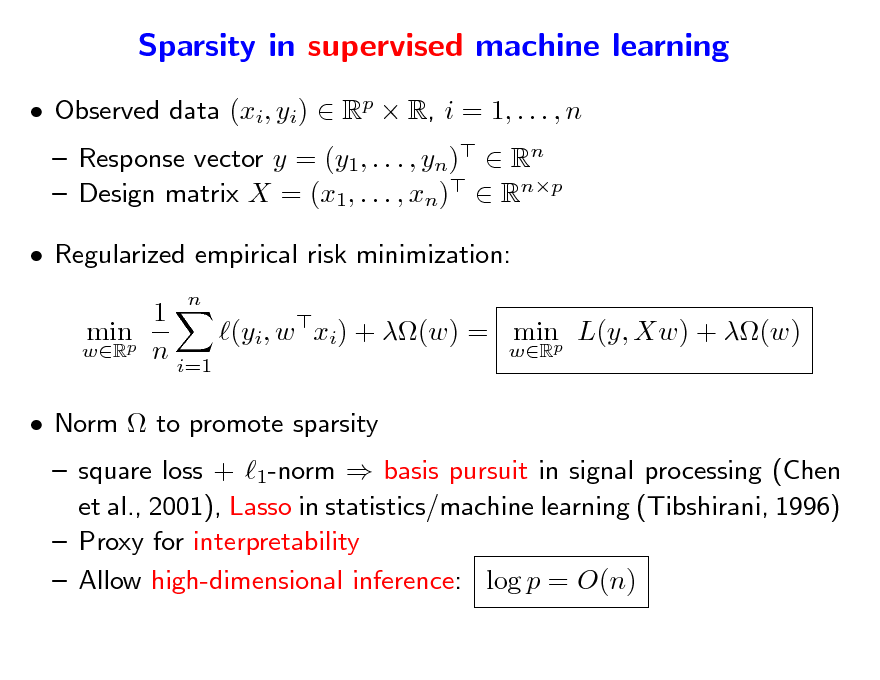

Sparsity in supervised machine learning

Observed data (xi, yi) Rp R, i = 1, . . . , n Response vector y = (y1, . . . , yn) Rn Design matrix X = (x1, . . . , xn) Rnp

n

Regularized empirical risk minimization: 1 minp (yi, w xi) + (w) = minp L(y, Xw) + (w) wR n wR i=1 Norm to promote sparsity

square loss + 1-norm basis pursuit in signal processing (Chen et al., 2001), Lasso in statistics/machine learning (Tibshirani, 1996) Proxy for interpretability Allow high-dimensional inference: log p = O(n)

98

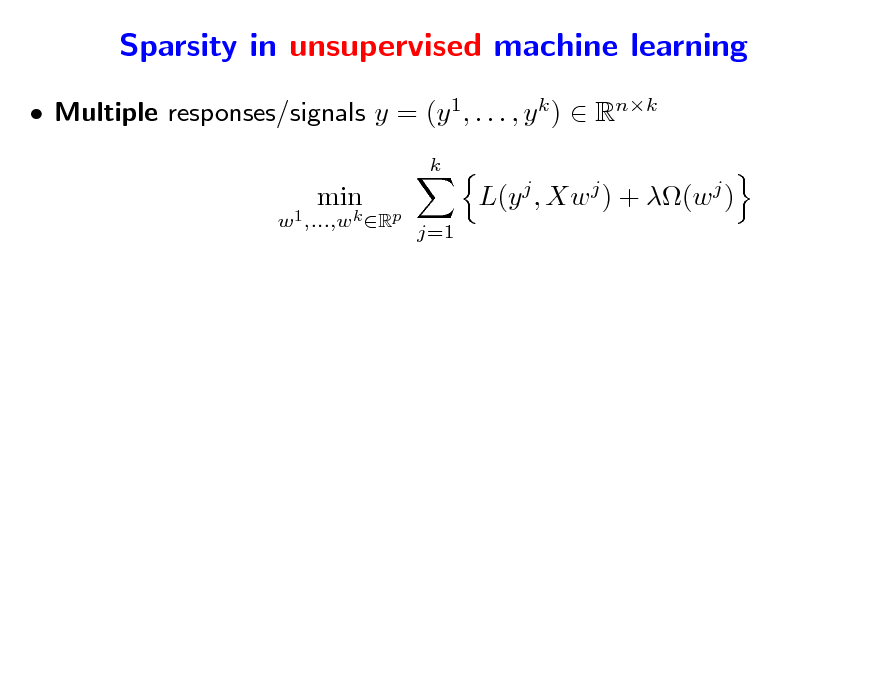

Sparsity in unsupervised machine learning

Multiple responses/signals y = (y 1, . . . , y k ) Rnk

k X=(x1 ,...,xp) w1 ,...,wk Rp

min

min

L(y j , Xw j ) + (w j )

j=1

99

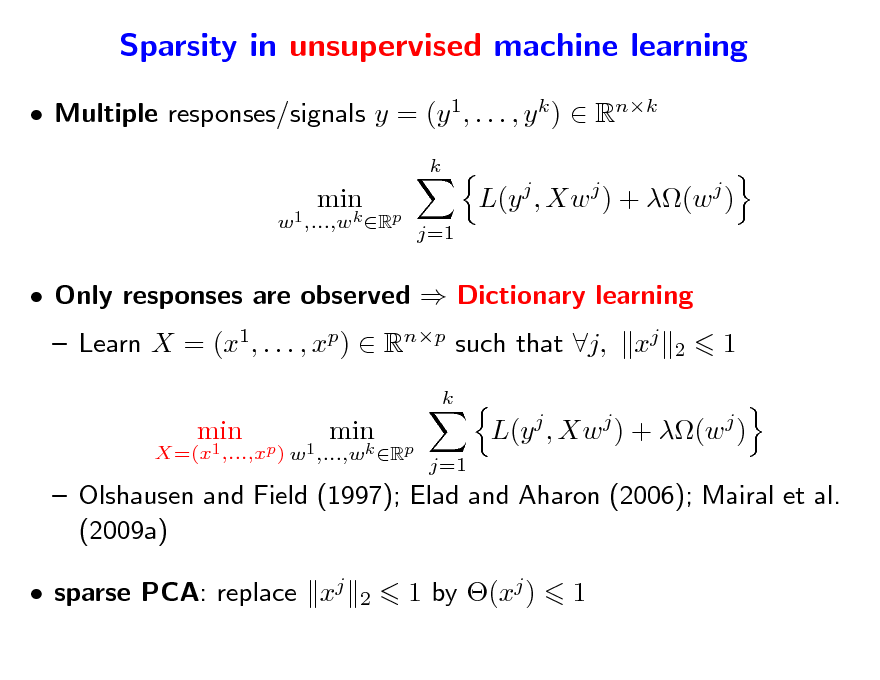

Sparsity in unsupervised machine learning

Multiple responses/signals y = (y 1, . . . , y k ) Rnk

k X=(x1 ,...,xp) w1 ,...,wk Rp

min

min

L(y j , Xw j ) + (w j )

j=1

Only responses are observed Dictionary learning Learn X = (x1, . . . , xp) Rnp such that j, xj

k X=(x1 ,...,xp ) w1 ,...,wk Rp 2

1

min

min

L(y j , Xw j ) + (w j )

j=1

Olshausen and Field (1997); Elad and Aharon (2006); Mairal et al. (2009a) sparse PCA: replace xj

2

1 by (xj )

1

100

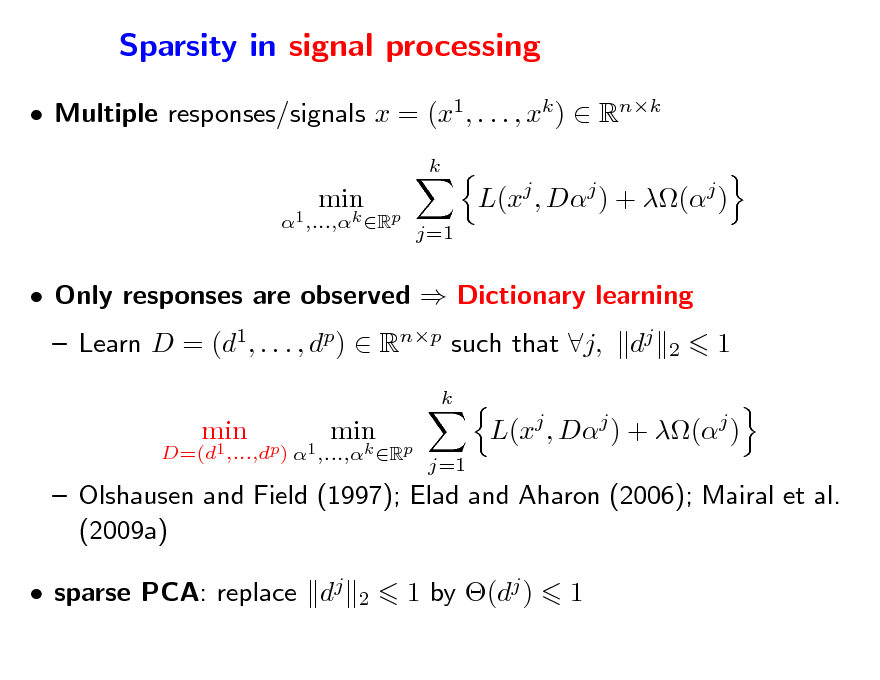

Sparsity in signal processing

Multiple responses/signals x = (x1, . . . , xk ) Rnk

k D=(d1,...,dp) 1 ,...,k Rp

min

min

L(xj , Dj ) + (j )

j=1

Only responses are observed Dictionary learning Learn D = (d1, . . . , dp) Rnp such that j,

k D=(d1 ,...,dp) 1 ,...,k Rp

dj

2

1

min

min

L(xj , Dj ) + (j )

j=1

Olshausen and Field (1997); Elad and Aharon (2006); Mairal et al. (2009a) sparse PCA: replace dj

2

1 by (dj )

1

101

Why structured sparsity?

Interpretability Structured dictionary elements (Jenatton et al., 2009b) Dictionary elements organized in a tree or a grid (Kavukcuoglu et al., 2009; Jenatton et al., 2010; Mairal et al., 2010)

102

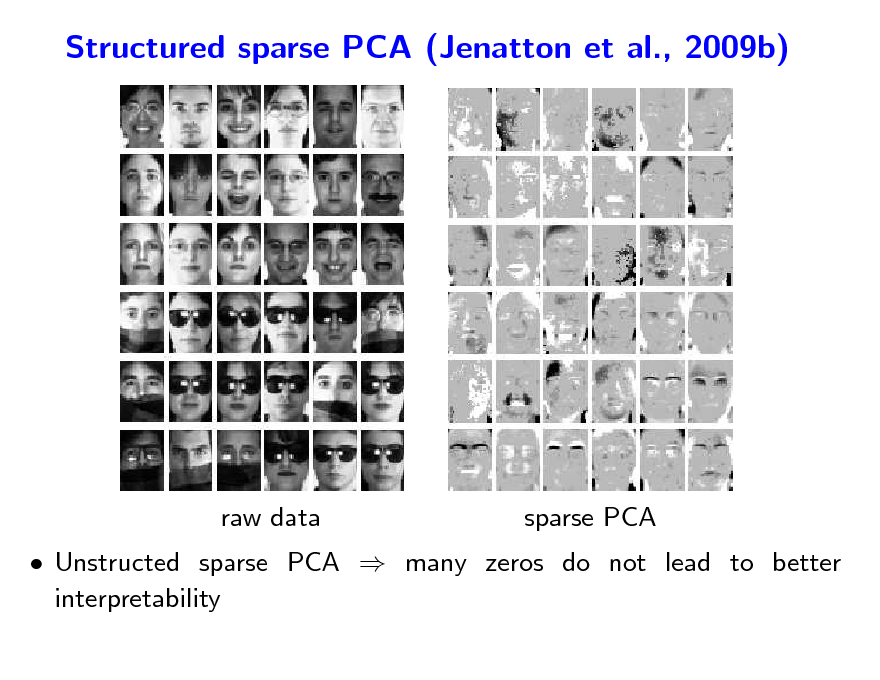

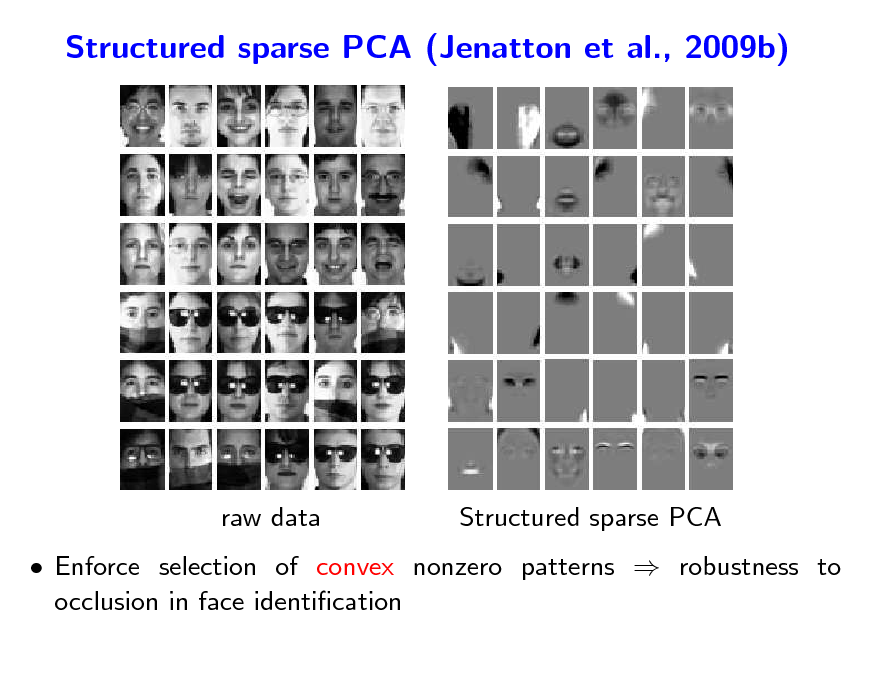

Structured sparse PCA (Jenatton et al., 2009b)

raw data

sparse PCA

Unstructed sparse PCA many zeros do not lead to better interpretability

103

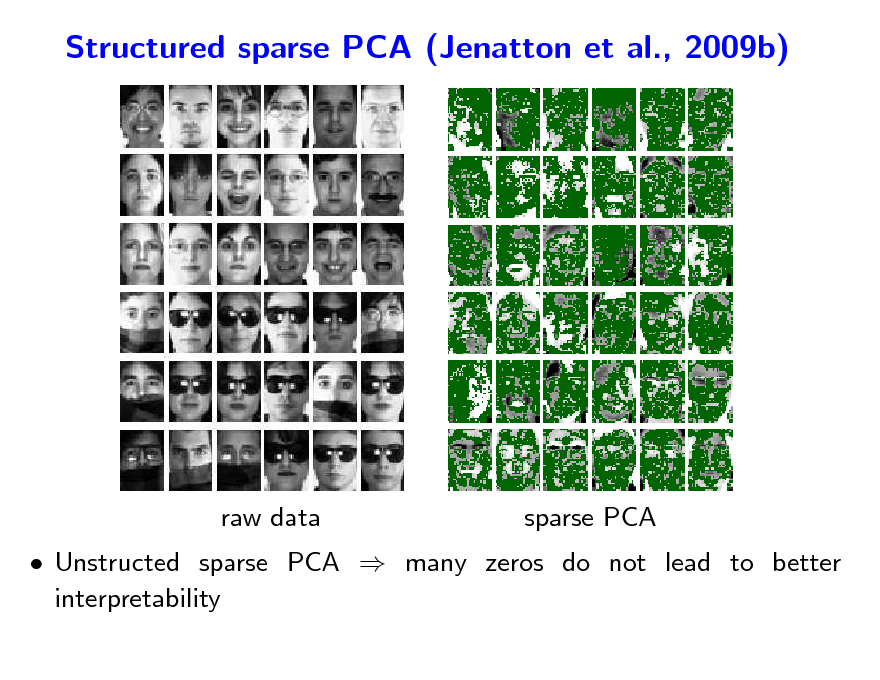

Structured sparse PCA (Jenatton et al., 2009b)

raw data

sparse PCA

Unstructed sparse PCA many zeros do not lead to better interpretability

104

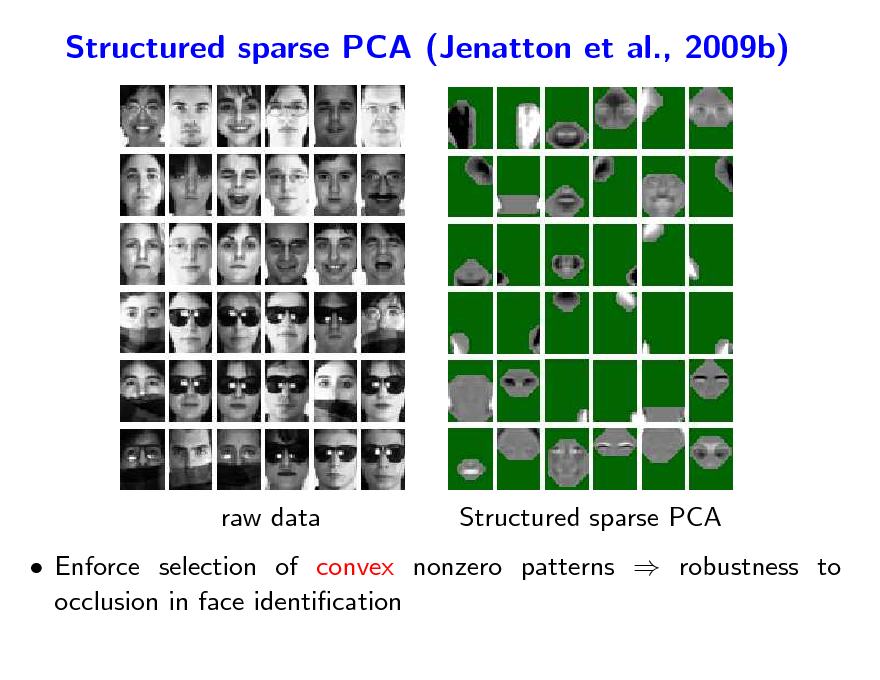

Structured sparse PCA (Jenatton et al., 2009b)

raw data

Structured sparse PCA

Enforce selection of convex nonzero patterns robustness to occlusion in face identication

105

Structured sparse PCA (Jenatton et al., 2009b)

raw data

Structured sparse PCA

Enforce selection of convex nonzero patterns robustness to occlusion in face identication

106

Why structured sparsity?

Interpretability Structured dictionary elements (Jenatton et al., 2009b) Dictionary elements organized in a tree or a grid (Kavukcuoglu et al., 2009; Jenatton et al., 2010; Mairal et al., 2010)

107

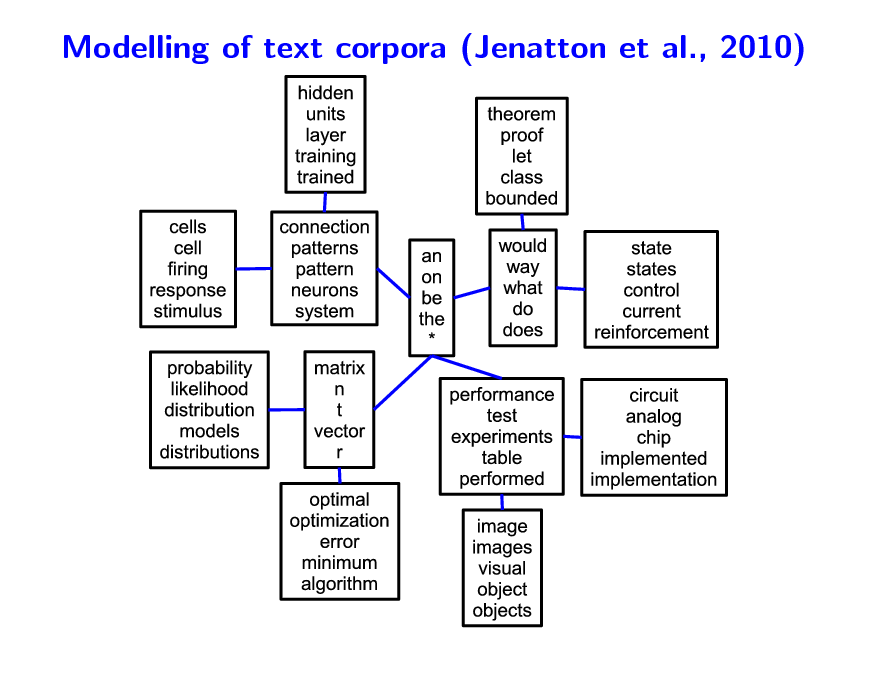

Modelling of text corpora (Jenatton et al., 2010)

108

Why structured sparsity?

Interpretability Structured dictionary elements (Jenatton et al., 2009b) Dictionary elements organized in a tree or a grid (Kavukcuoglu et al., 2009; Jenatton et al., 2010; Mairal et al., 2010)

109

Why structured sparsity?

Interpretability Structured dictionary elements (Jenatton et al., 2009b) Dictionary elements organized in a tree or a grid (Kavukcuoglu et al., 2009; Jenatton et al., 2010; Mairal et al., 2010) Stability and identiability Optimization problem minwRp L(y, Xw) + w 1 is unstable Codes w j often used in later processing (Mairal et al., 2009c) Prediction or estimation performance When prior knowledge matches data (Haupt and Nowak, 2006; Baraniuk et al., 2008; Jenatton et al., 2009a; Huang et al., 2009) Numerical eciency

Non-linear variable selection with 2p subsets (Bach, 2008)

110

Classical approaches to structured sparsity

Many application domains Computer vision (Cevher et al., 2008; Mairal et al., 2009b) Neuro-imaging (Gramfort and Kowalski, 2009; Jenatton et al., 2011) Bio-informatics (Rapaport et al., 2008; Kim and Xing, 2010) Non-convex approaches Haupt and Nowak (2006); Baraniuk et al. (2008); Huang et al. (2009) Convex approaches Design of sparsity-inducing norms

111

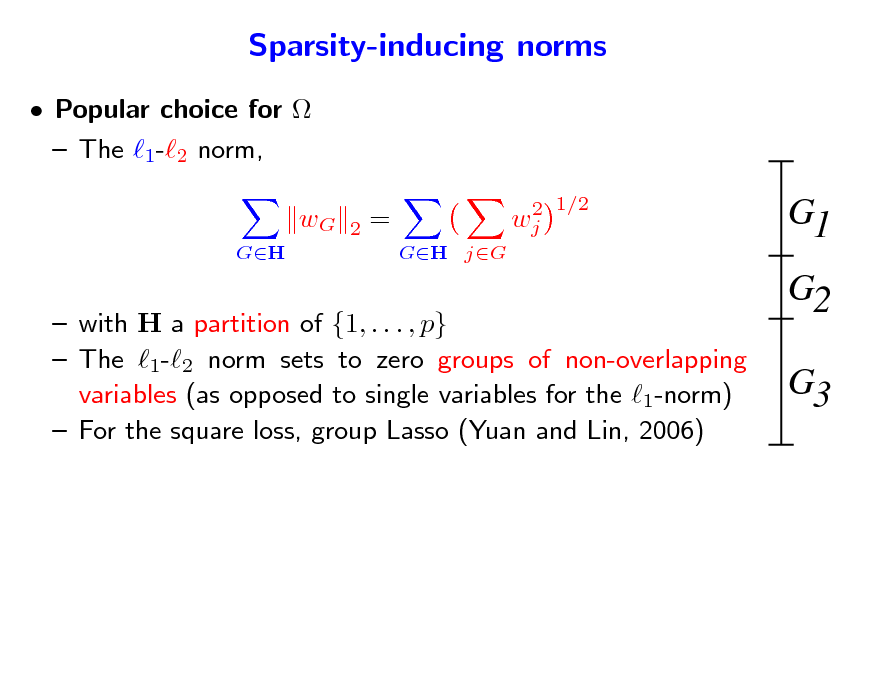

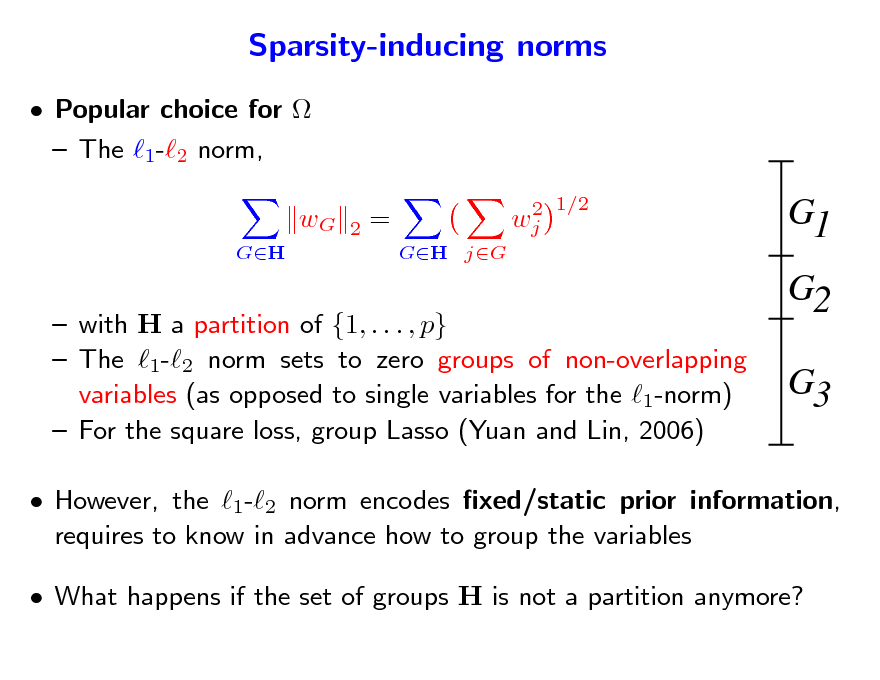

Sparsity-inducing norms

Popular choice for The 1-2 norm, wG

GH 2 = GH jG 2 wj 1/2

G1 G2 G3

with H a partition of {1, . . . , p} The 1-2 norm sets to zero groups of non-overlapping variables (as opposed to single variables for the 1-norm) For the square loss, group Lasso (Yuan and Lin, 2006)

112

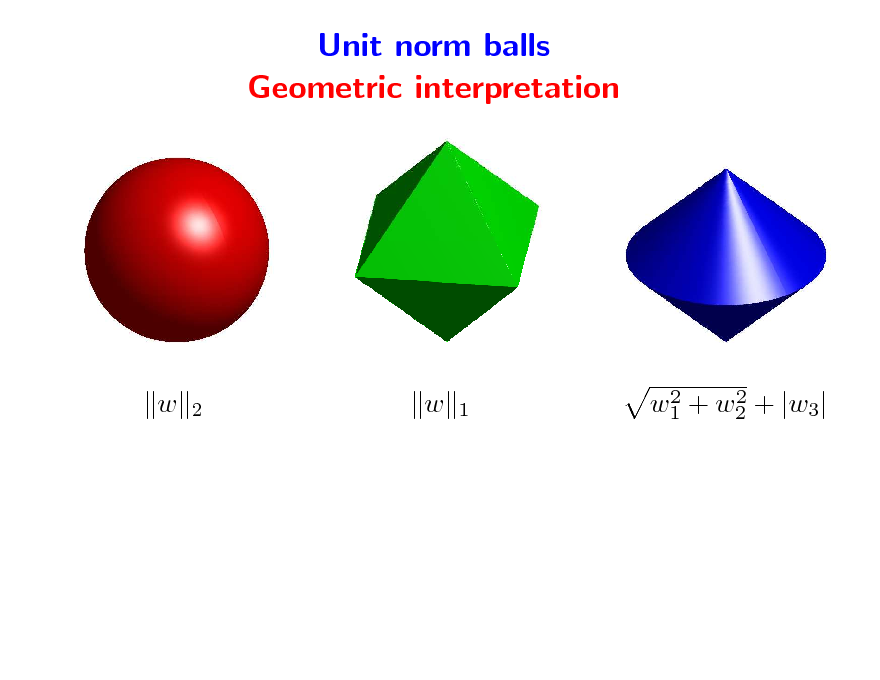

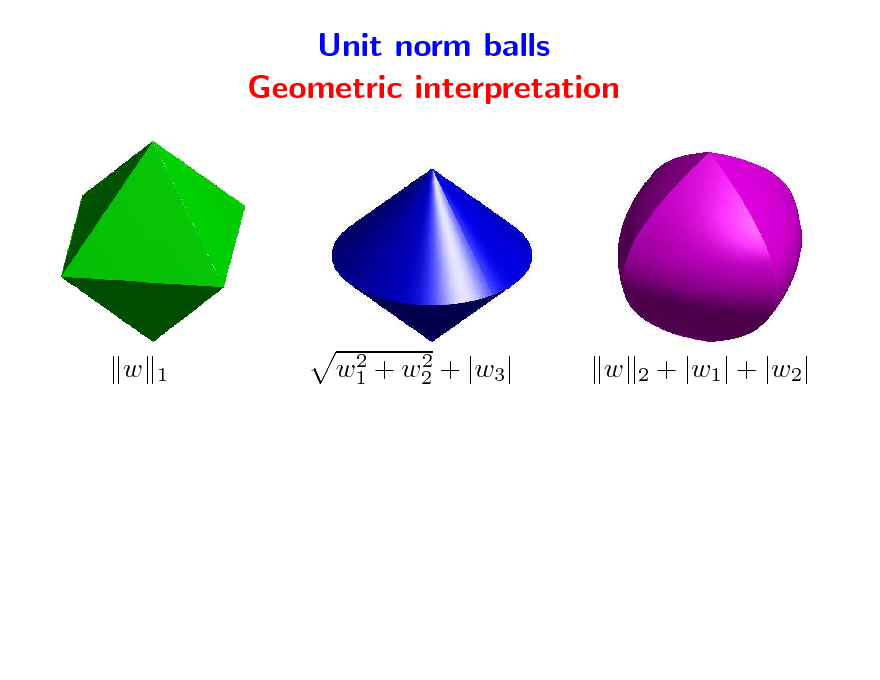

Unit norm balls Geometric interpretation

w

2

w

1

2 2 w1 + w2 + |w3|

113

Sparsity-inducing norms

Popular choice for The 1-2 norm, wG

GH 2 = GH jG 2 wj 1/2

G1 G2 G3

with H a partition of {1, . . . , p} The 1-2 norm sets to zero groups of non-overlapping variables (as opposed to single variables for the 1-norm) For the square loss, group Lasso (Yuan and Lin, 2006)

However, the 1-2 norm encodes xed/static prior information, requires to know in advance how to group the variables What happens if the set of groups H is not a partition anymore?

114

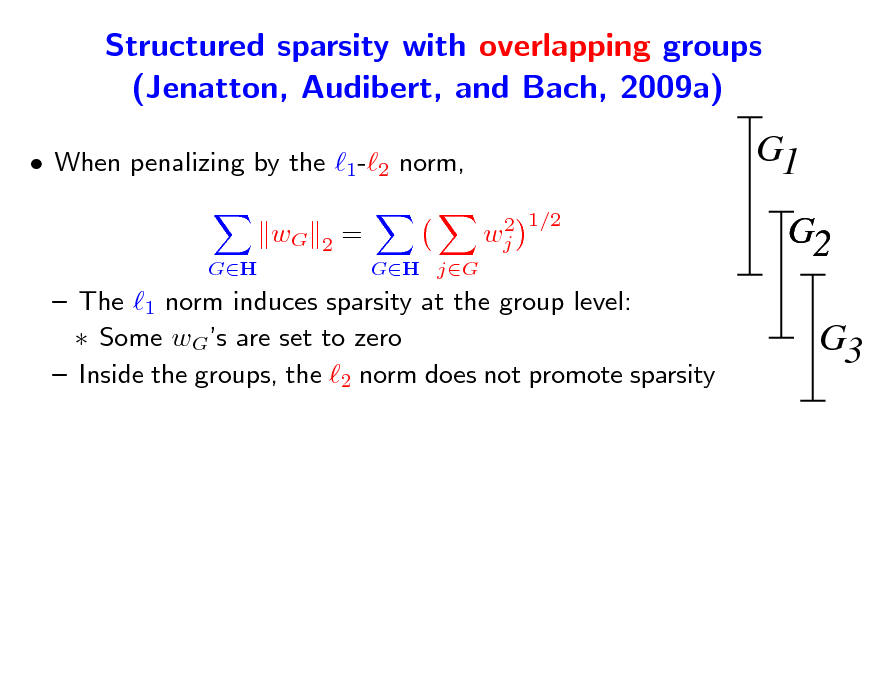

Structured sparsity with overlapping groups (Jenatton, Audibert, and Bach, 2009a)

When penalizing by the 1-2 norm, wG

GH 2

G1

2 1/2 wj

=

GH jG

G2 G3

The 1 norm induces sparsity at the group level: Some wGs are set to zero Inside the groups, the 2 norm does not promote sparsity

115

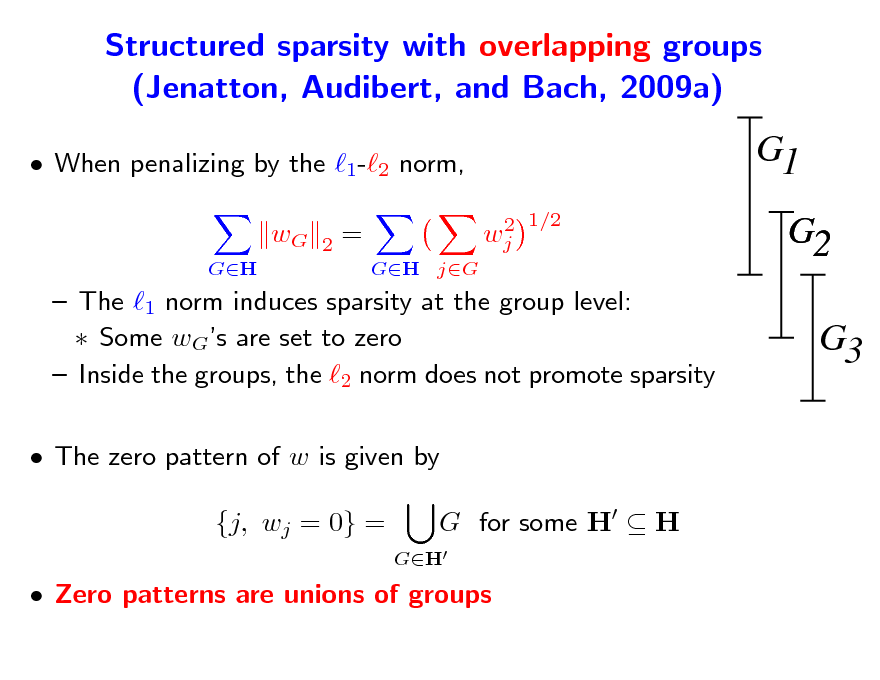

Structured sparsity with overlapping groups (Jenatton, Audibert, and Bach, 2009a)

When penalizing by the 1-2 norm, wG

GH 2

G1

2 1/2 wj

=

GH jG

G2 G3

The 1 norm induces sparsity at the group level: Some wGs are set to zero Inside the groups, the 2 norm does not promote sparsity The zero pattern of w is given by {j, wj = 0} =

GH

G for some H H

Zero patterns are unions of groups

116

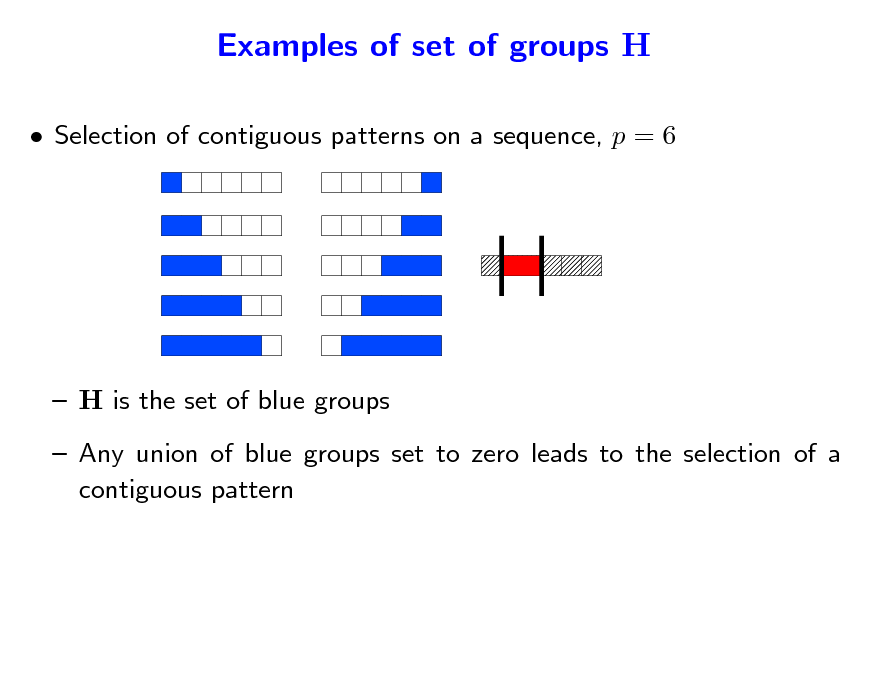

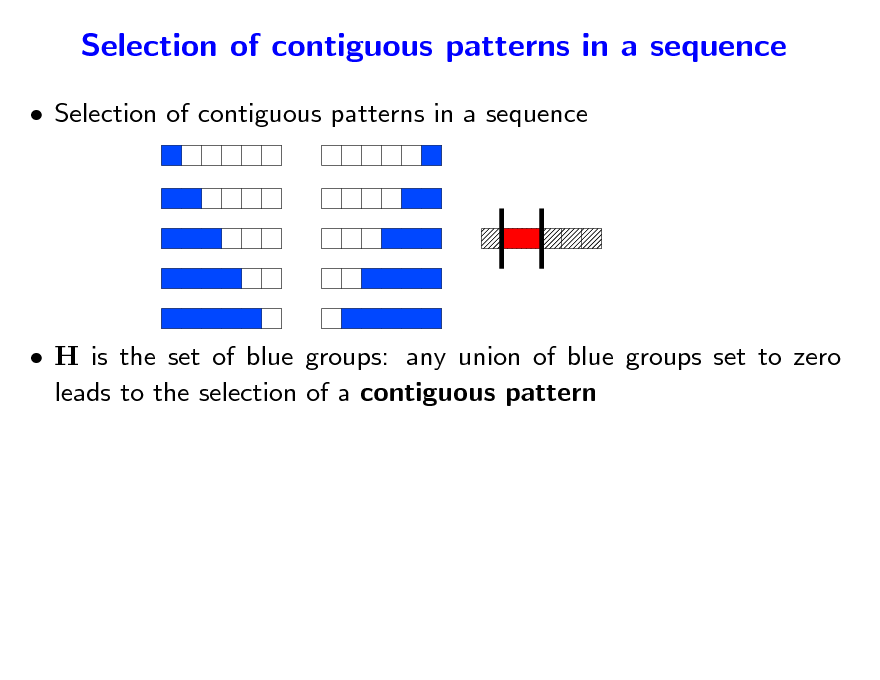

Examples of set of groups H

Selection of contiguous patterns on a sequence, p = 6

H is the set of blue groups Any union of blue groups set to zero leads to the selection of a contiguous pattern

117

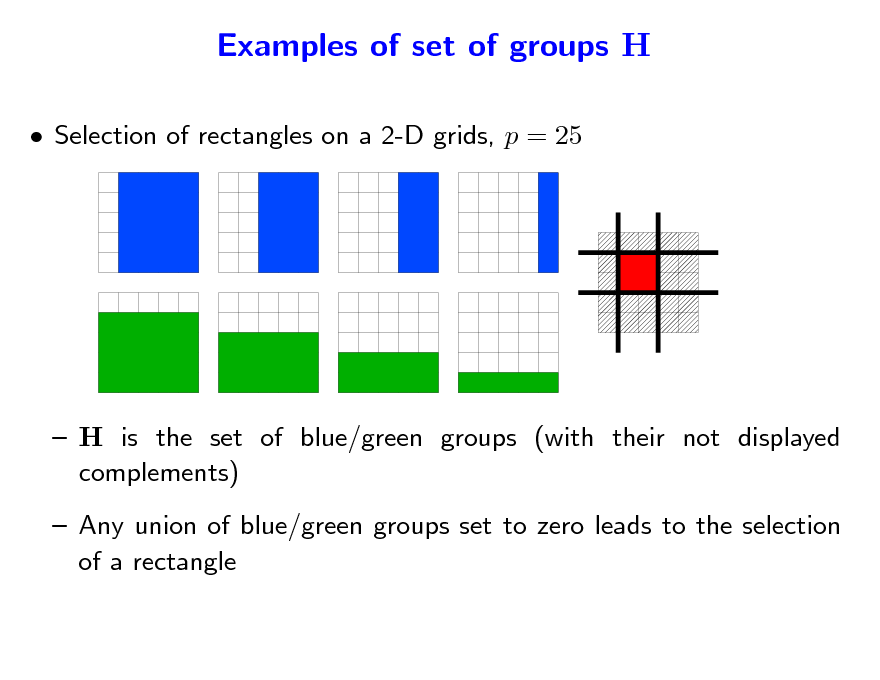

Examples of set of groups H

Selection of rectangles on a 2-D grids, p = 25

H is the set of blue/green groups (with their not displayed complements) Any union of blue/green groups set to zero leads to the selection of a rectangle

118

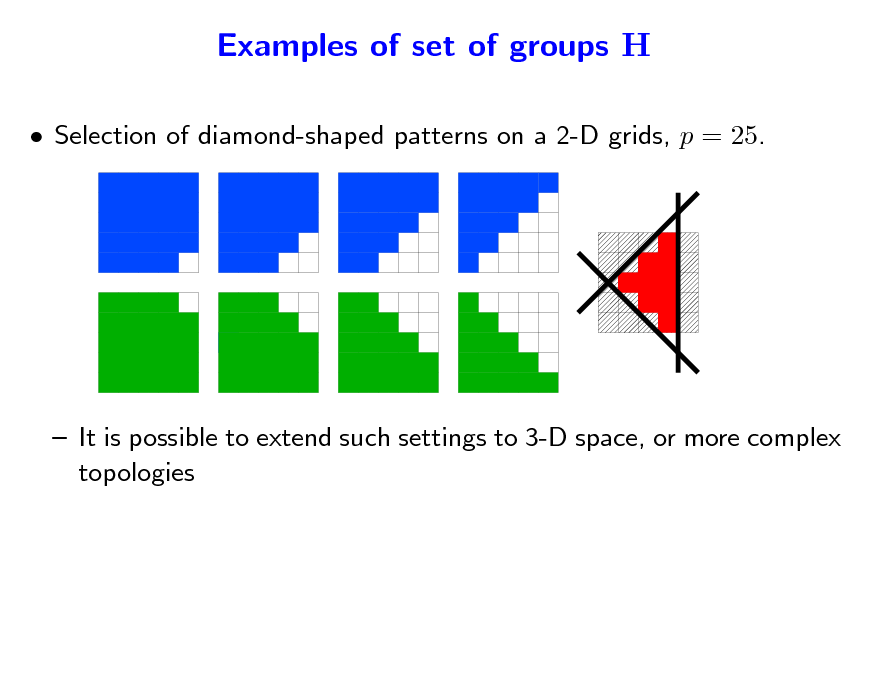

Examples of set of groups H

Selection of diamond-shaped patterns on a 2-D grids, p = 25.

It is possible to extend such settings to 3-D space, or more complex topologies

119

Unit norm balls Geometric interpretation

w

1

2 2 w1 + w2 + |w3|

w

2

+ |w1| + |w2|

120

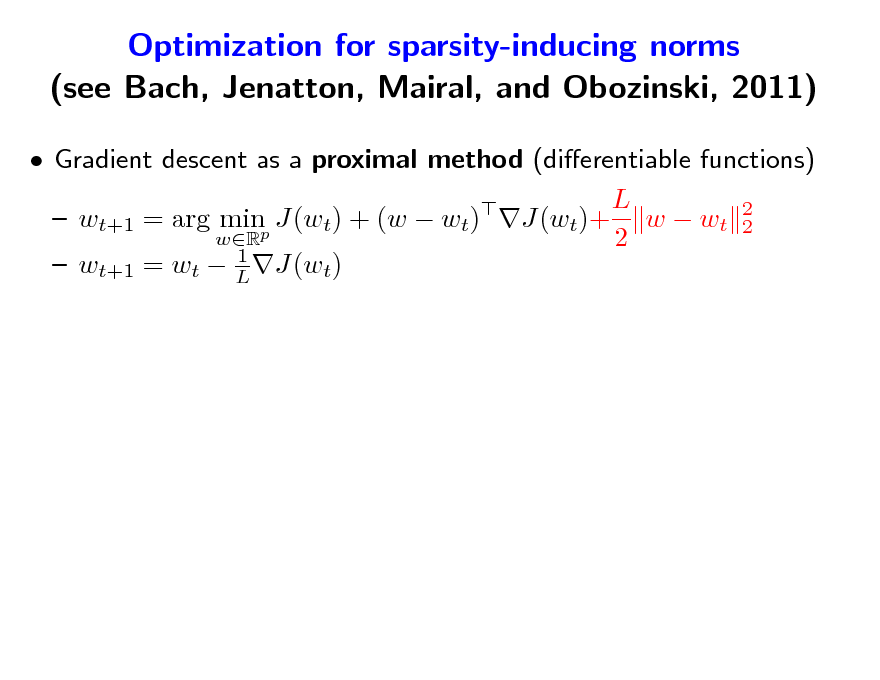

Optimization for sparsity-inducing norms (see Bach, Jenatton, Mairal, and Obozinski, 2011)

Gradient descent as a proximal method (dierentiable functions) L wt+1 = arg minp J(wt) + (w wt) J(wt)+ w wt 2 2 wR 2 1 wt+1 = wt L J(wt)

121

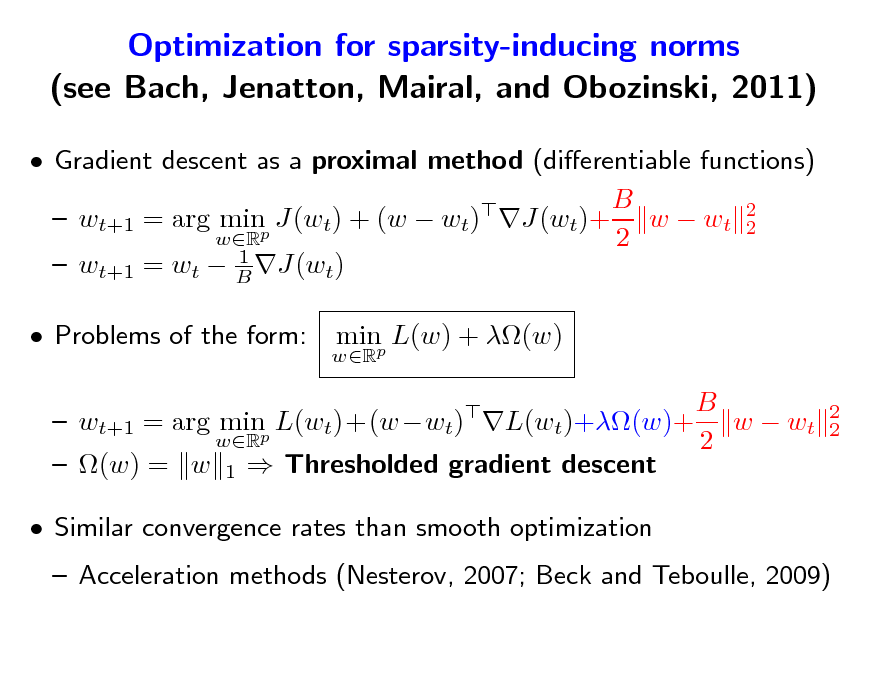

Optimization for sparsity-inducing norms (see Bach, Jenatton, Mairal, and Obozinski, 2011)

Gradient descent as a proximal method (dierentiable functions) B wt+1 = arg minp J(wt) + (w wt) J(wt)+ w wt 2 2 wR 2 1 wt+1 = wt B J(wt) Problems of the form:

wR

minp L(w) + (w)

2 2

B wt+1 = arg minp L(wt)+(wwt) L(wt)+(w)+ w wt wR 2 (w) = w 1 Thresholded gradient descent Similar convergence rates than smooth optimization

Acceleration methods (Nesterov, 2007; Beck and Teboulle, 2009)

122

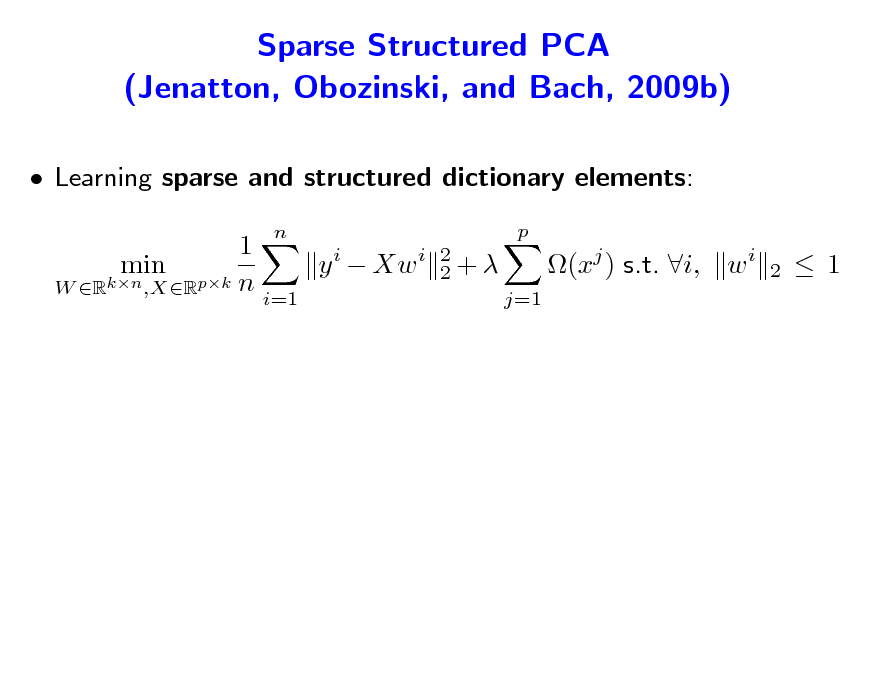

Sparse Structured PCA (Jenatton, Obozinski, and Bach, 2009b)

Learning sparse and structured dictionary elements: 1 y i Xw i min W Rkn ,XRpk n i=1

n p 2 2+ j=1

(xj ) s.t. i, w i

2

1

123

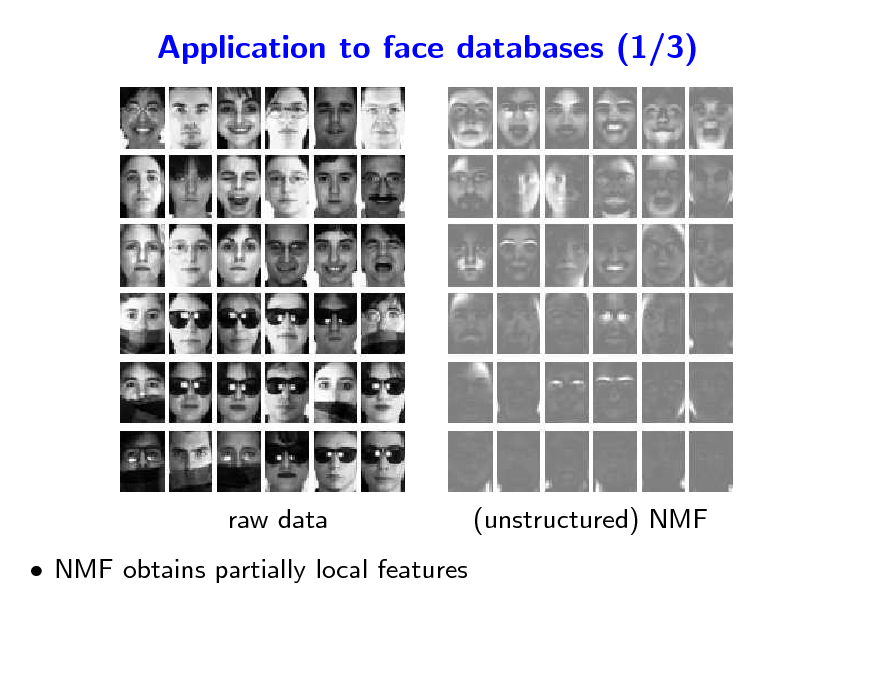

Application to face databases (1/3)

raw data NMF obtains partially local features

(unstructured) NMF

124

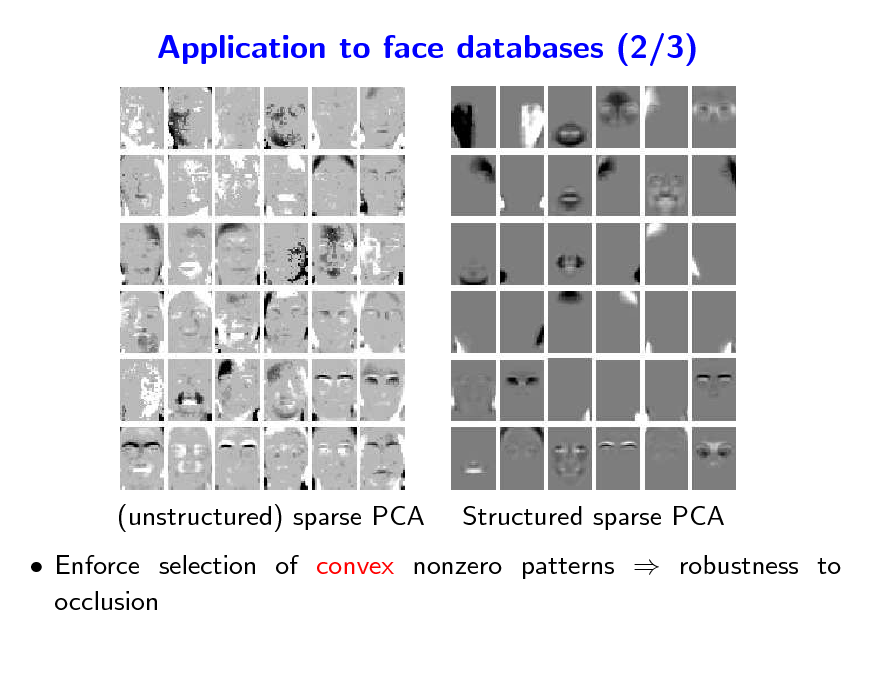

Application to face databases (2/3)

(unstructured) sparse PCA

Structured sparse PCA

Enforce selection of convex nonzero patterns robustness to occlusion

125

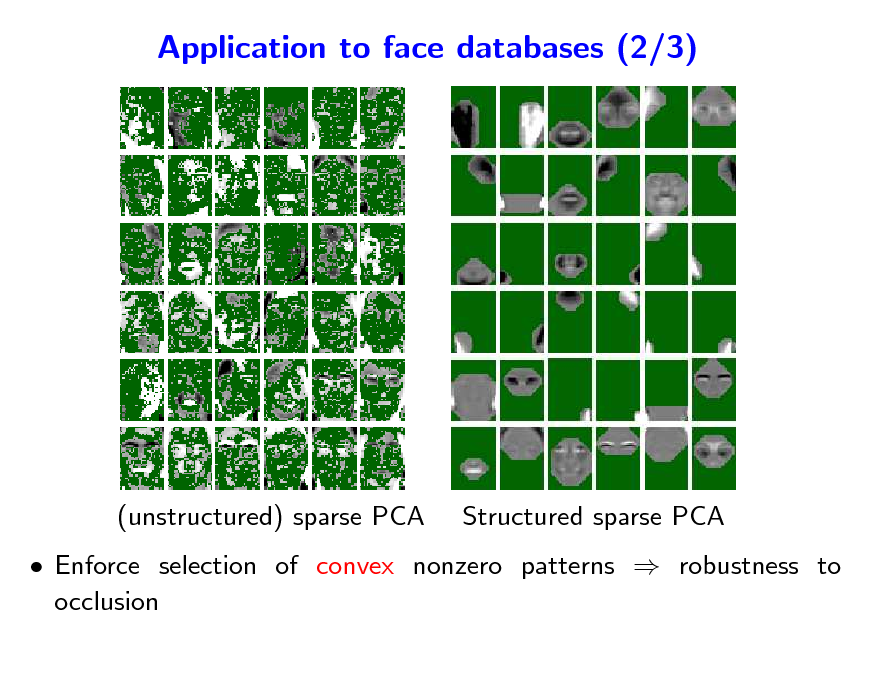

Application to face databases (2/3)

(unstructured) sparse PCA

Structured sparse PCA

Enforce selection of convex nonzero patterns robustness to occlusion

126

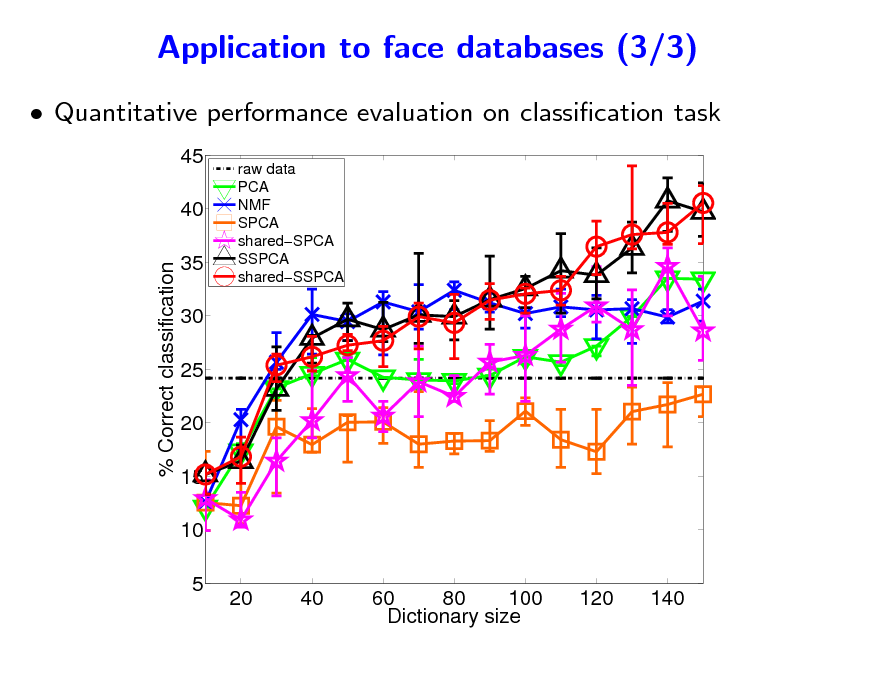

Application to face databases (3/3)

Quantitative performance evaluation on classication task

45 40 % Correct classification 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 20 40 60 80 100 Dictionary size 120 140

raw data PCA NMF SPCA sharedSPCA SSPCA sharedSSPCA

127

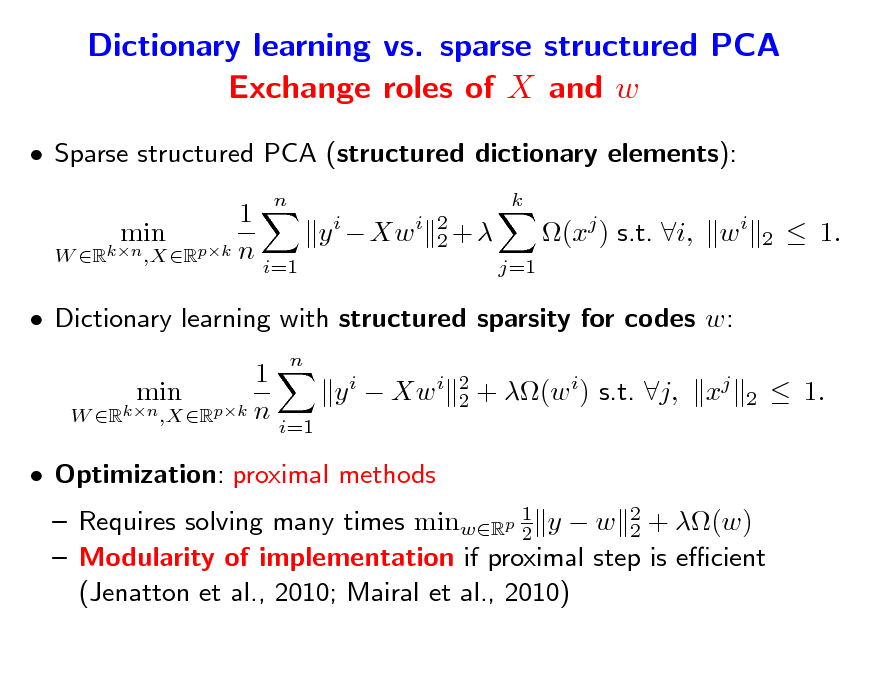

Dictionary learning vs. sparse structured PCA Exchange roles of X and w

Sparse structured PCA (structured dictionary elements): 1 y i Xw i min W Rkn ,XRpk n i=1

n k 2 2+ j=1

(xj ) s.t. i, w i

2

1.

Dictionary learning with structured sparsity for codes w: 1 min y i Xw i W Rkn ,XRpk n i=1 Optimization: proximal methods

n 2 2

+ (w i) s.t. j,

xj

2

1.

Requires solving many times minwRp 1 y w 2 + (w) 2 2 Modularity of implementation if proximal step is ecient (Jenatton et al., 2010; Mairal et al., 2010)

128

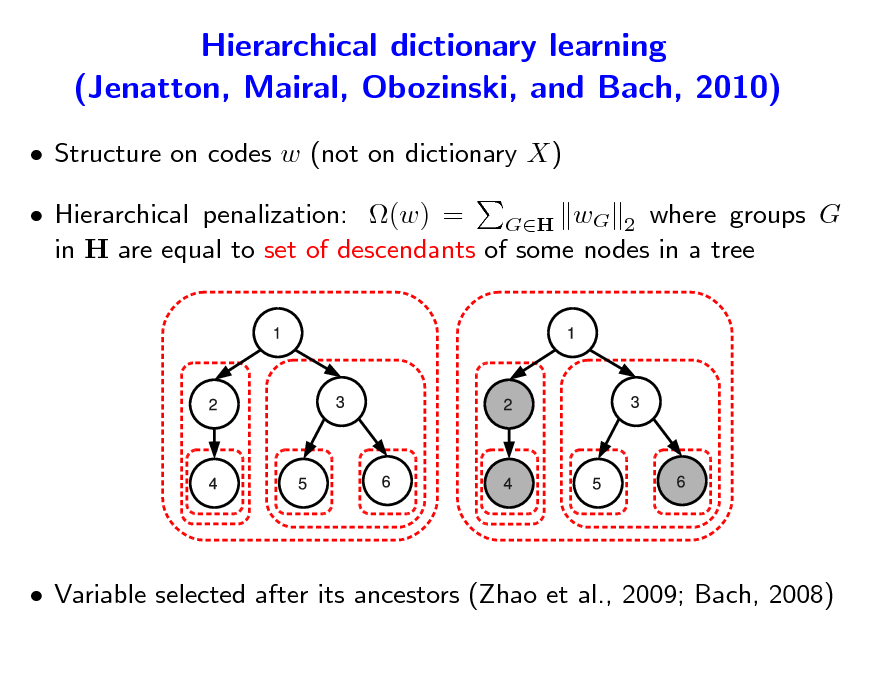

Hierarchical dictionary learning (Jenatton, Mairal, Obozinski, and Bach, 2010)

Structure on codes w (not on dictionary X) Hierarchical penalization: (w) = GH wG 2 where groups G in H are equal to set of descendants of some nodes in a tree

Variable selected after its ancestors (Zhao et al., 2009; Bach, 2008)

129

Hierarchical dictionary learning Modelling of text corpora

Each document is modelled through word counts Low-rank matrix factorization of word-document matrix Probabilistic topic models (Blei et al., 2003) Similar structures based on non parametric Bayesian methods (Blei et al., 2004) Can we achieve similar performance with simple matrix factorization formulation?

130

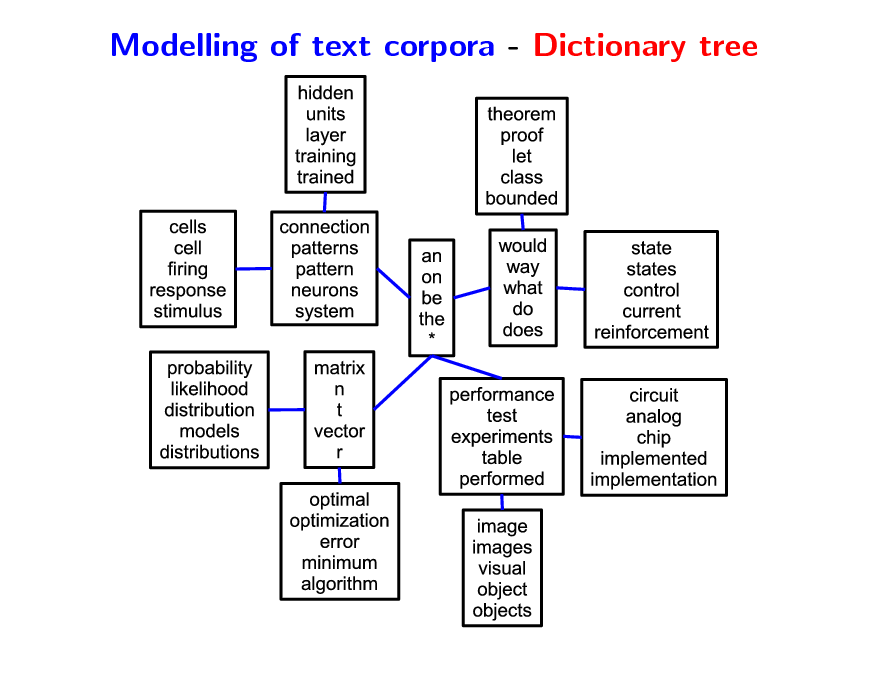

Modelling of text corpora - Dictionary tree

131

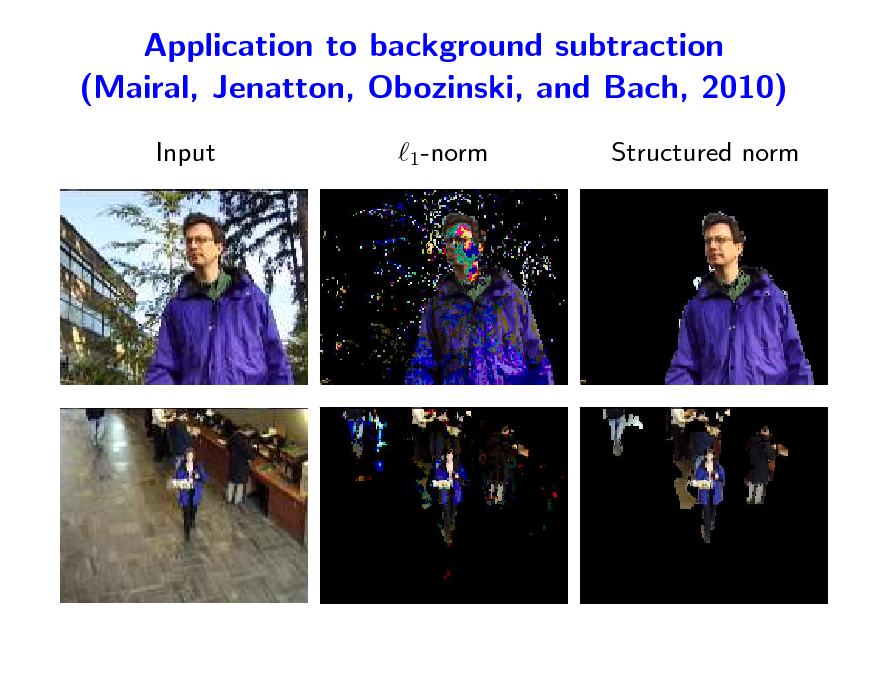

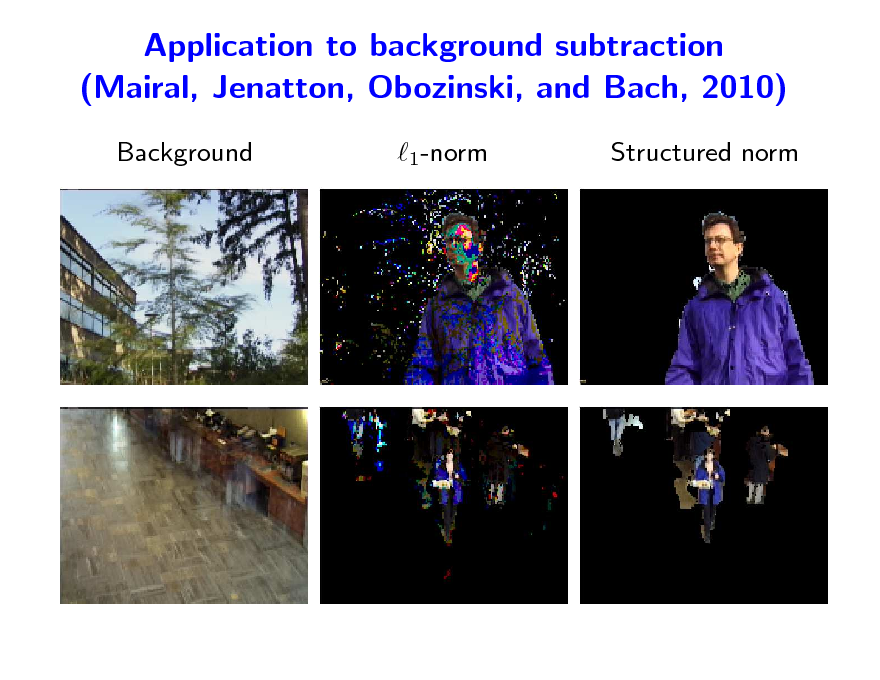

Application to background subtraction (Mairal, Jenatton, Obozinski, and Bach, 2010)

Input 1-norm Structured norm

132

Application to background subtraction (Mairal, Jenatton, Obozinski, and Bach, 2010)

Background 1-norm Structured norm

133

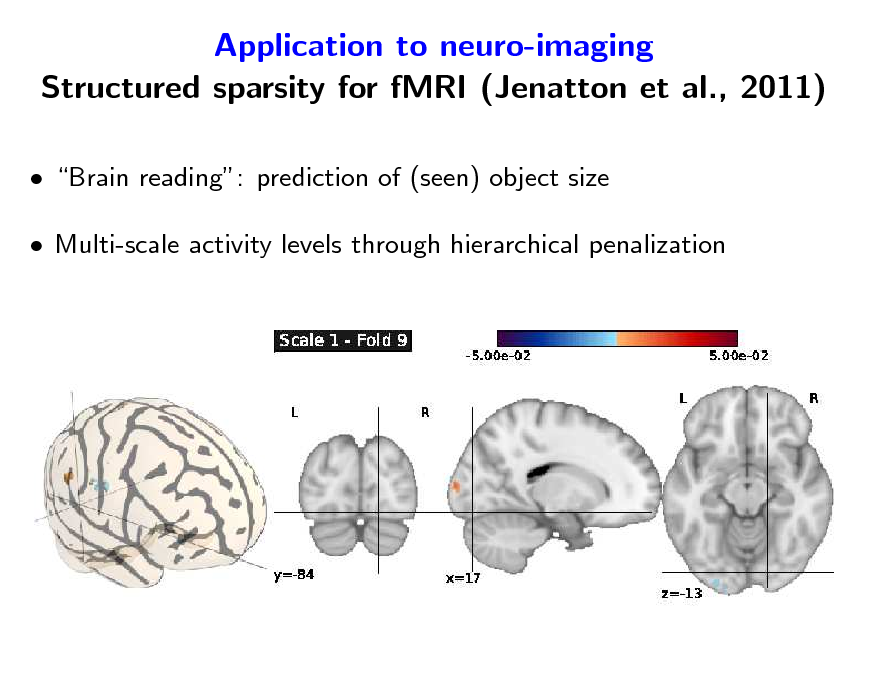

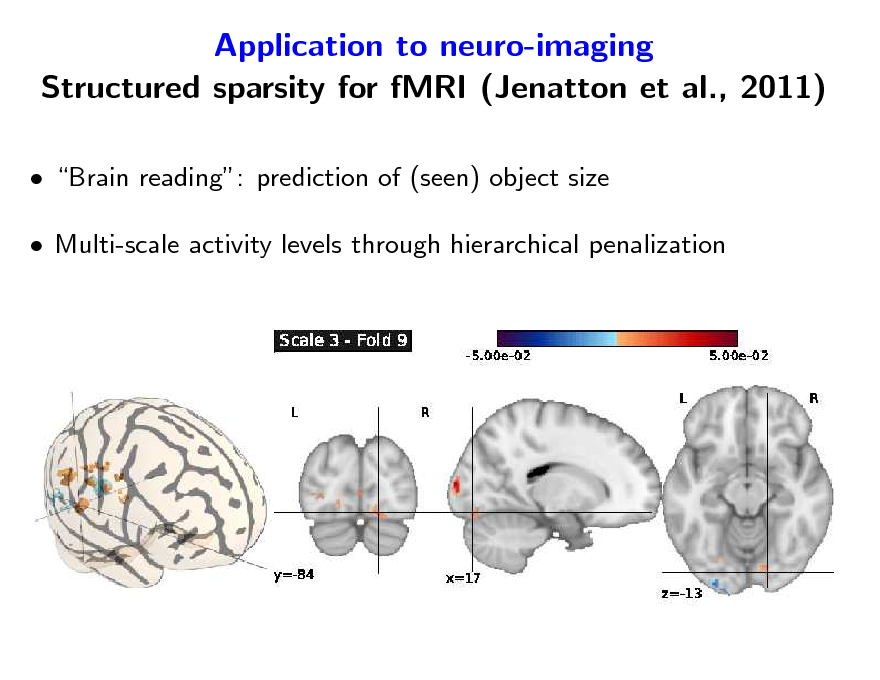

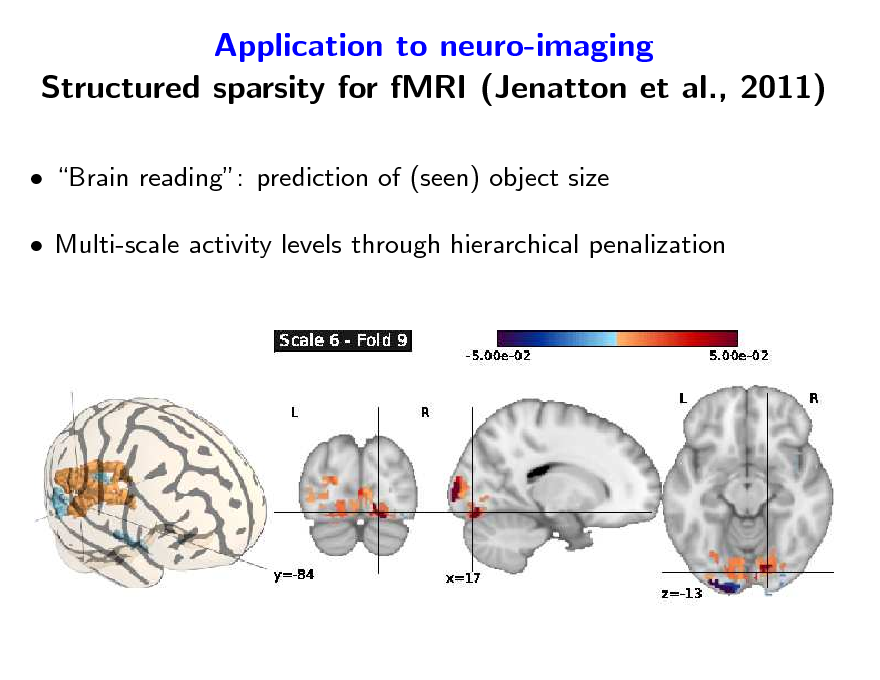

Application to neuro-imaging Structured sparsity for fMRI (Jenatton et al., 2011)

Brain reading: prediction of (seen) object size Multi-scale activity levels through hierarchical penalization

134

Application to neuro-imaging Structured sparsity for fMRI (Jenatton et al., 2011)

Brain reading: prediction of (seen) object size Multi-scale activity levels through hierarchical penalization

135

Application to neuro-imaging Structured sparsity for fMRI (Jenatton et al., 2011)

Brain reading: prediction of (seen) object size Multi-scale activity levels through hierarchical penalization

136

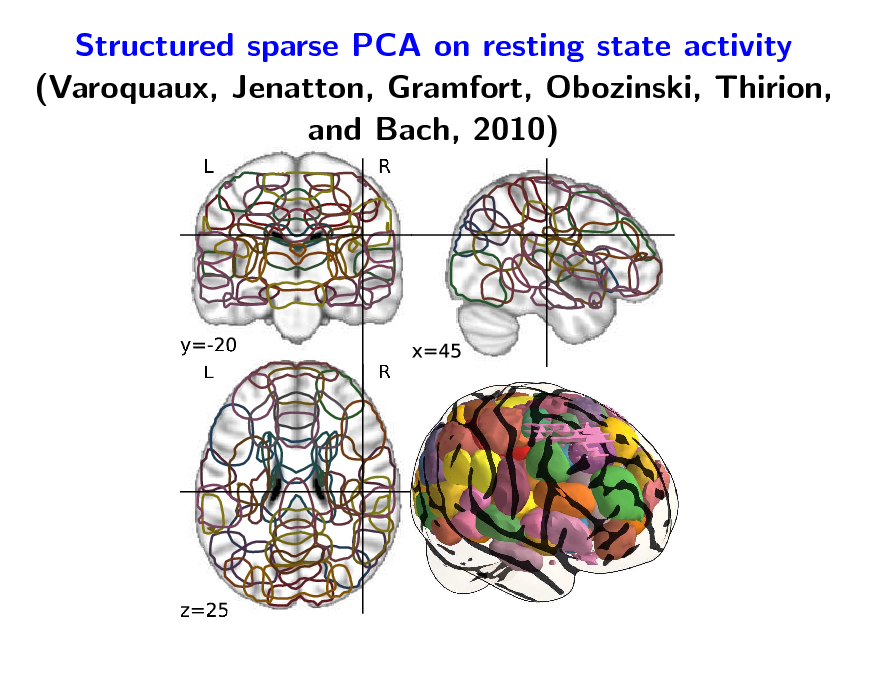

Structured sparse PCA on resting state activity (Varoquaux, Jenatton, Gramfort, Obozinski, Thirion, and Bach, 2010)

137

![Slide: 1-norm = convex envelope of cardinality of support

Let w Rp. Let V = {1, . . . , p} and Supp(w) = {j V, wj = 0} Cardinality of support: w

0

= Card(Supp(w))

Convex envelope = largest convex lower bound (see, e.g., Boyd and Vandenberghe, 2004)

||w|| 0

||w|| 1

1

1

1-norm = convex envelope of 0-quasi-norm on the -ball [1, 1]p](https://yosinski.com/mlss12/media/slides/MLSS-2012-Bach-Learning-with-Submodular-Functions_138.png)

1-norm = convex envelope of cardinality of support

Let w Rp. Let V = {1, . . . , p} and Supp(w) = {j V, wj = 0} Cardinality of support: w

0

= Card(Supp(w))

Convex envelope = largest convex lower bound (see, e.g., Boyd and Vandenberghe, 2004)

||w|| 0

||w|| 1

1

1

1-norm = convex envelope of 0-quasi-norm on the -ball [1, 1]p

138

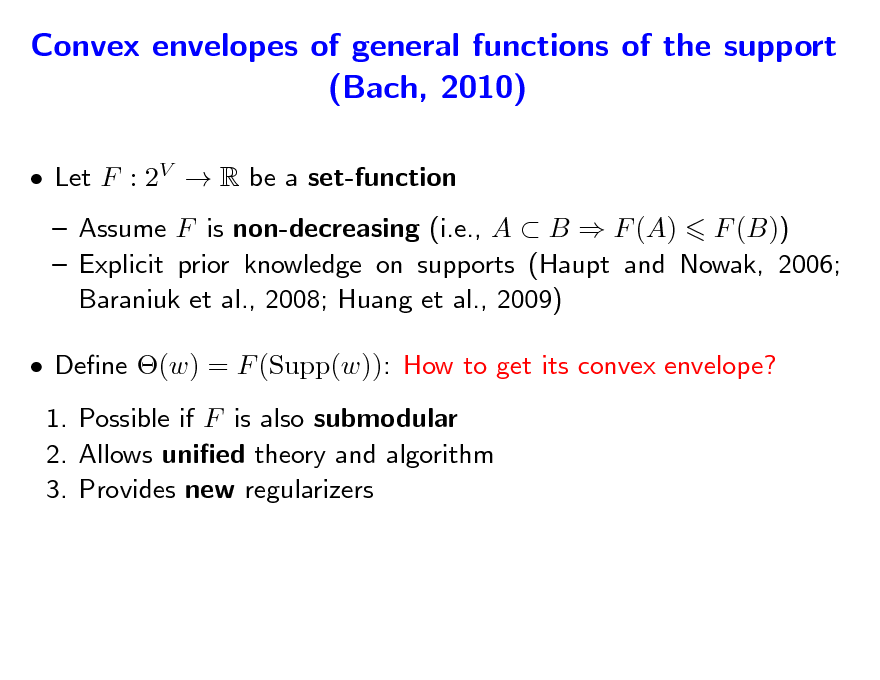

Convex envelopes of general functions of the support (Bach, 2010)

Let F : 2V R be a set-function Assume F is non-decreasing (i.e., A B F (A) F (B)) Explicit prior knowledge on supports (Haupt and Nowak, 2006; Baraniuk et al., 2008; Huang et al., 2009) Dene (w) = F (Supp(w)): How to get its convex envelope? 1. Possible if F is also submodular 2. Allows unied theory and algorithm 3. Provides new regularizers

139

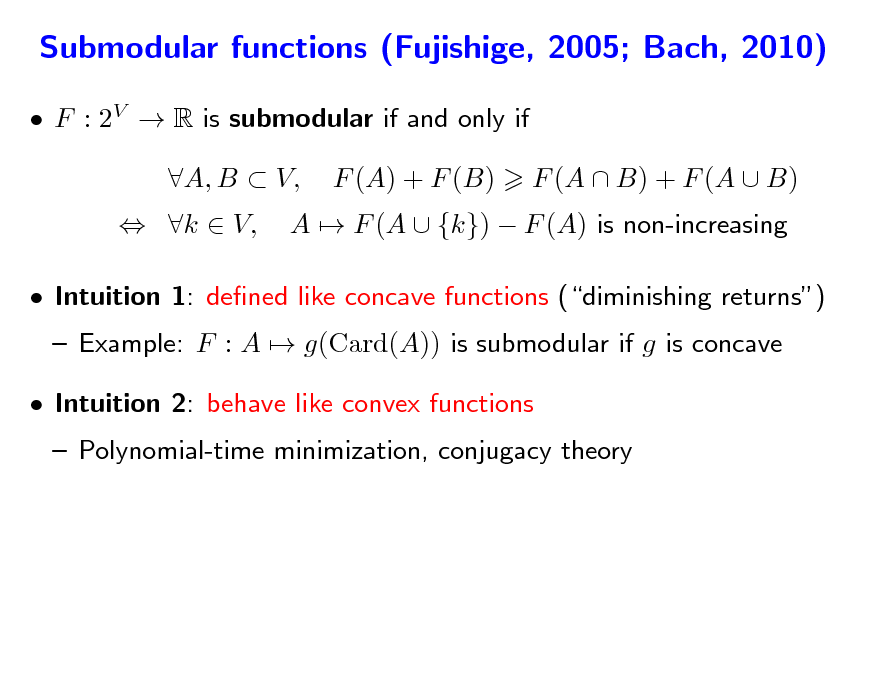

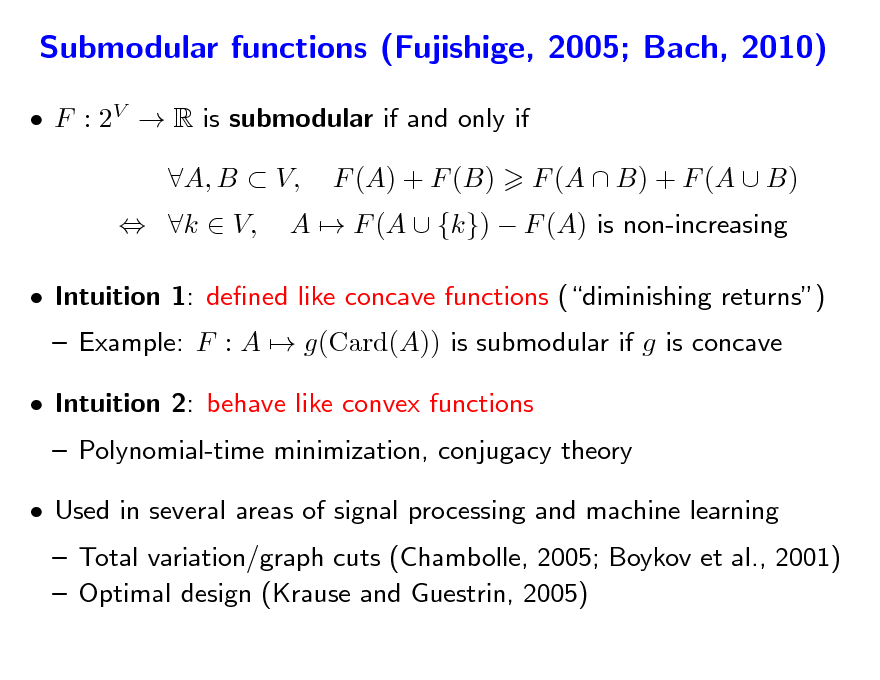

Submodular functions (Fujishige, 2005; Bach, 2010)

F : 2V R is submodular if and only if k V, A, B V, F (A) + F (B) A F (A {k}) F (A) is non-increasing F (A B) + F (A B)

140

Submodular functions (Fujishige, 2005; Bach, 2010)

F : 2V R is submodular if and only if k V, A, B V, F (A) + F (B) A F (A {k}) F (A) is non-increasing F (A B) + F (A B)

Intuition 1: dened like concave functions (diminishing returns) Example: F : A g(Card(A)) is submodular if g is concave

141

Submodular functions (Fujishige, 2005; Bach, 2010)

F : 2V R is submodular if and only if k V, A, B V, F (A) + F (B) A F (A {k}) F (A) is non-increasing F (A B) + F (A B)

Intuition 1: dened like concave functions (diminishing returns) Example: F : A g(Card(A)) is submodular if g is concave Polynomial-time minimization, conjugacy theory Intuition 2: behave like convex functions

142

Submodular functions (Fujishige, 2005; Bach, 2010)

F : 2V R is submodular if and only if k V, A, B V, F (A) + F (B) A F (A {k}) F (A) is non-increasing F (A B) + F (A B)

Intuition 1: dened like concave functions (diminishing returns) Example: F : A g(Card(A)) is submodular if g is concave Polynomial-time minimization, conjugacy theory Intuition 2: behave like convex functions

Used in several areas of signal processing and machine learning

Total variation/graph cuts (Chambolle, 2005; Boykov et al., 2001) Optimal design (Krause and Guestrin, 2005)

143

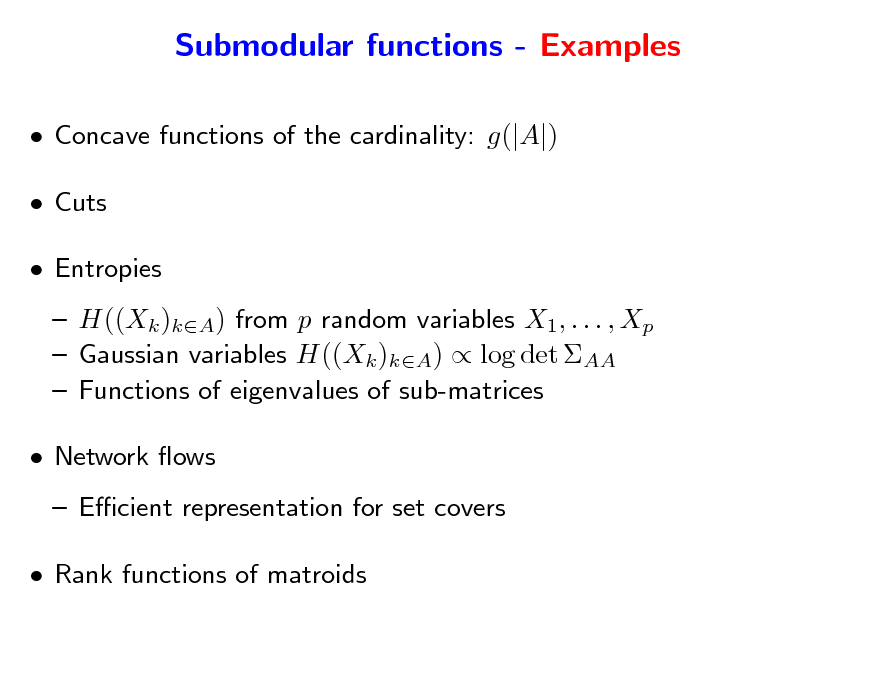

Submodular functions - Examples

Concave functions of the cardinality: g(|A|) Cuts Entropies H((Xk )kA) from p random variables X1, . . . , Xp Gaussian variables H((Xk )kA) log det AA Functions of eigenvalues of sub-matrices Network ows Ecient representation for set covers Rank functions of matroids

144

![Slide: Submodular functions - Lovsz extension a

Subsets may be identied with elements of {0, 1}p Given any set-function F and w such that wj1

p

wjp , dene:

f (w) =

k=1

wjk [F ({j1, . . . , jk }) F ({j1, . . . , jk1})]

If w = 1A, f (w) = F (A) extension from {0, 1}p to Rp f is piecewise ane and positively homogeneous F is submodular if and only if f is convex (Lovsz, 1982) a](https://yosinski.com/mlss12/media/slides/MLSS-2012-Bach-Learning-with-Submodular-Functions_145.png)

Submodular functions - Lovsz extension a

Subsets may be identied with elements of {0, 1}p Given any set-function F and w such that wj1

p

wjp , dene:

f (w) =

k=1

wjk [F ({j1, . . . , jk }) F ({j1, . . . , jk1})]

If w = 1A, f (w) = F (A) extension from {0, 1}p to Rp f is piecewise ane and positively homogeneous F is submodular if and only if f is convex (Lovsz, 1982) a

145

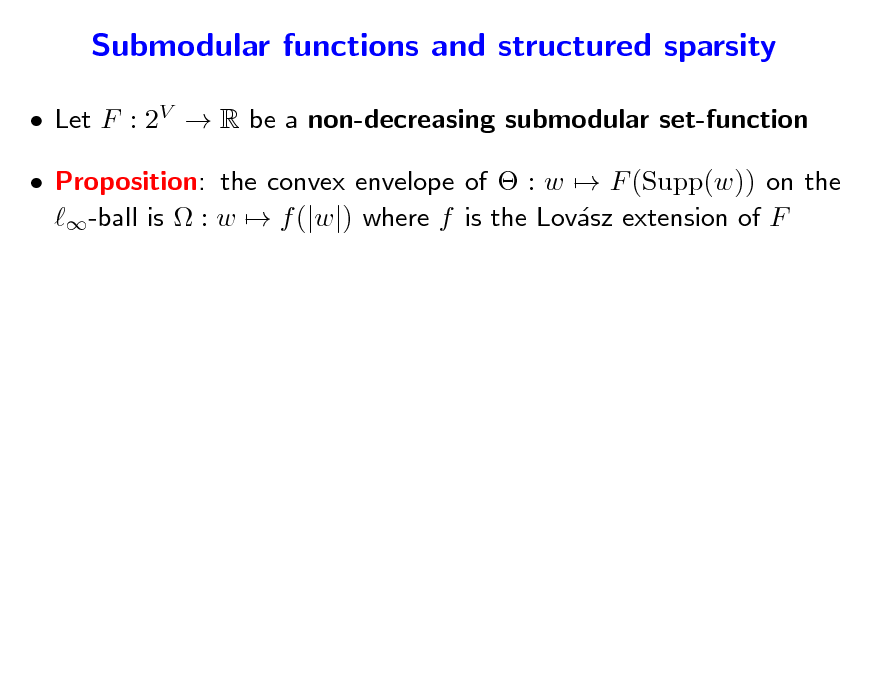

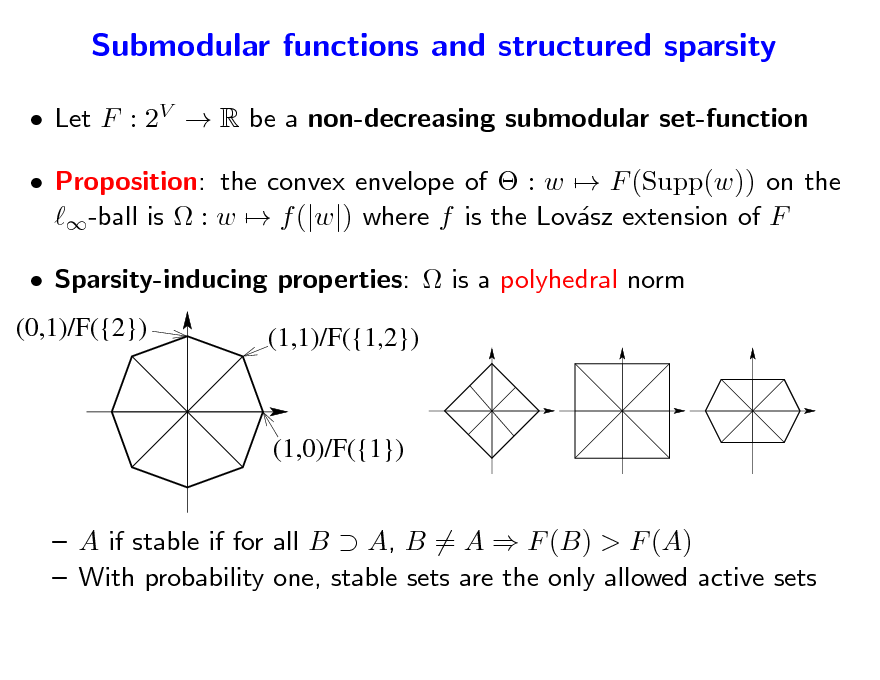

Submodular functions and structured sparsity

Let F : 2V R be a non-decreasing submodular set-function Proposition: the convex envelope of : w F (Supp(w)) on the -ball is : w f (|w|) where f is the Lovsz extension of F a

146

Submodular functions and structured sparsity

Let F : 2V R be a non-decreasing submodular set-function Proposition: the convex envelope of : w F (Supp(w)) on the -ball is : w f (|w|) where f is the Lovsz extension of F a Sparsity-inducing properties: is a polyhedral norm

(0,1)/F({2}) (1,1)/F({1,2})

(1,0)/F({1})

A if stable if for all B A, B = A F (B) > F (A) With probability one, stable sets are the only allowed active sets

147

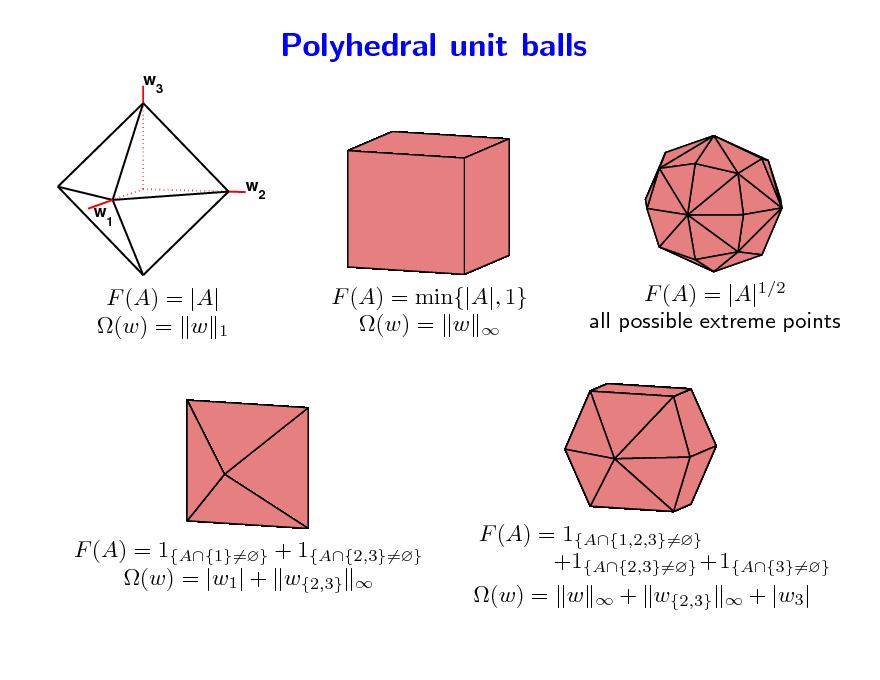

Polyhedral unit balls

w3

w w

1

2

F (A) = |A| (w) = w 1

F (A) = min{|A|, 1} (w) = w

F (A) = |A|1/2 all possible extreme points

F (A) = 1{A{1}=} + 1{A{2,3}=} (w) = |w1| + w{2,3}

F (A) = 1{A{1,2,3}=} +1{A{2,3}=} +1{A{3}=} (w) = w + w{2,3} + |w3|

148

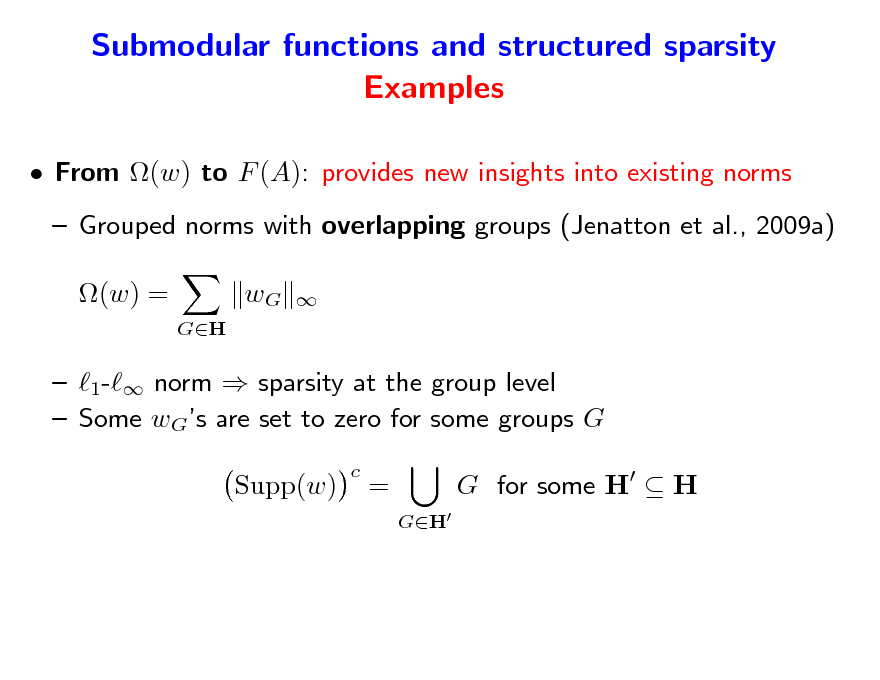

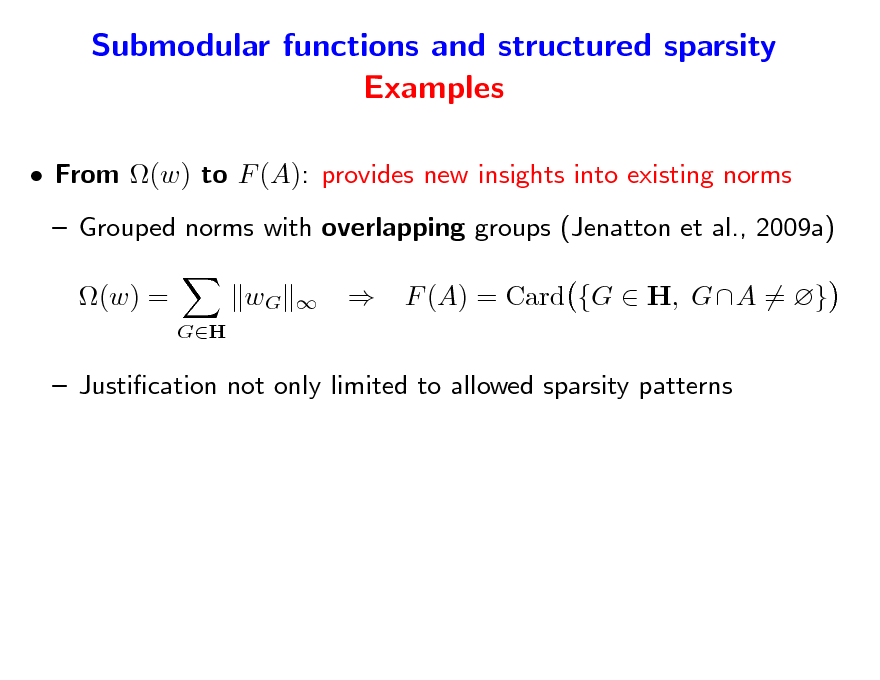

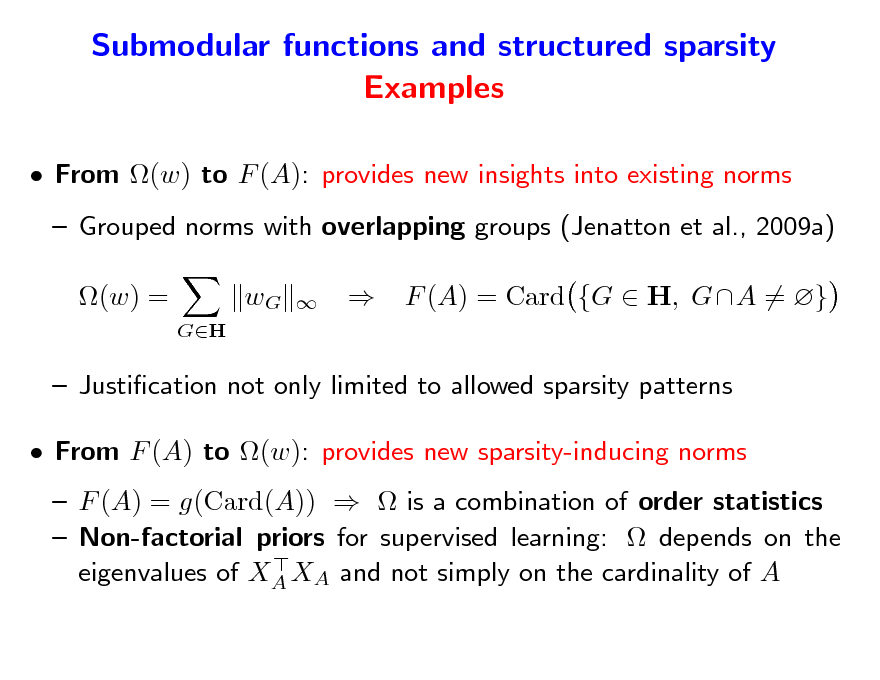

Submodular functions and structured sparsity Examples

From (w) to F (A): provides new insights into existing norms Grouped norms with overlapping groups (Jenatton et al., 2009a) (w) =

GH

wG

1- norm sparsity at the group level Some wGs are set to zero for some groups G Supp(w)

c

=

GH

G for some H H

149

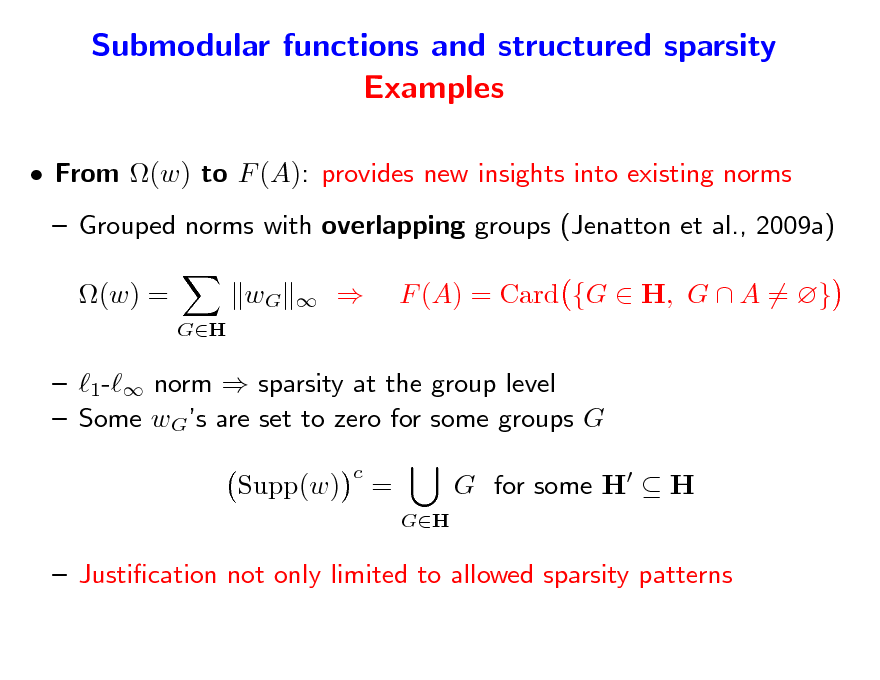

Submodular functions and structured sparsity Examples

From (w) to F (A): provides new insights into existing norms Grouped norms with overlapping groups (Jenatton et al., 2009a) (w) =

GH

wG

F (A) = Card {G H, G A = }

1- norm sparsity at the group level Some wGs are set to zero for some groups G Supp(w)

c

=

GH

G for some H H

Justication not only limited to allowed sparsity patterns

150

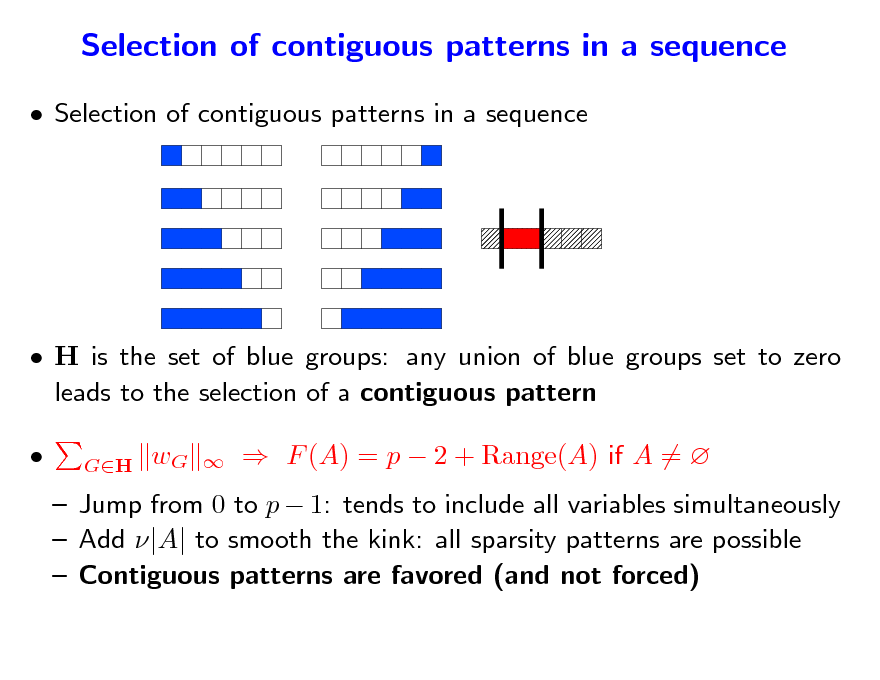

Selection of contiguous patterns in a sequence

Selection of contiguous patterns in a sequence

H is the set of blue groups: any union of blue groups set to zero leads to the selection of a contiguous pattern

151

Selection of contiguous patterns in a sequence

Selection of contiguous patterns in a sequence

H is the set of blue groups: any union of blue groups set to zero leads to the selection of a contiguous pattern

GH

wG

F (A) = p 2 + Range(A) if A =

Jump from 0 to p 1: tends to include all variables simultaneously Add |A| to smooth the kink: all sparsity patterns are possible Contiguous patterns are favored (and not forced)

152

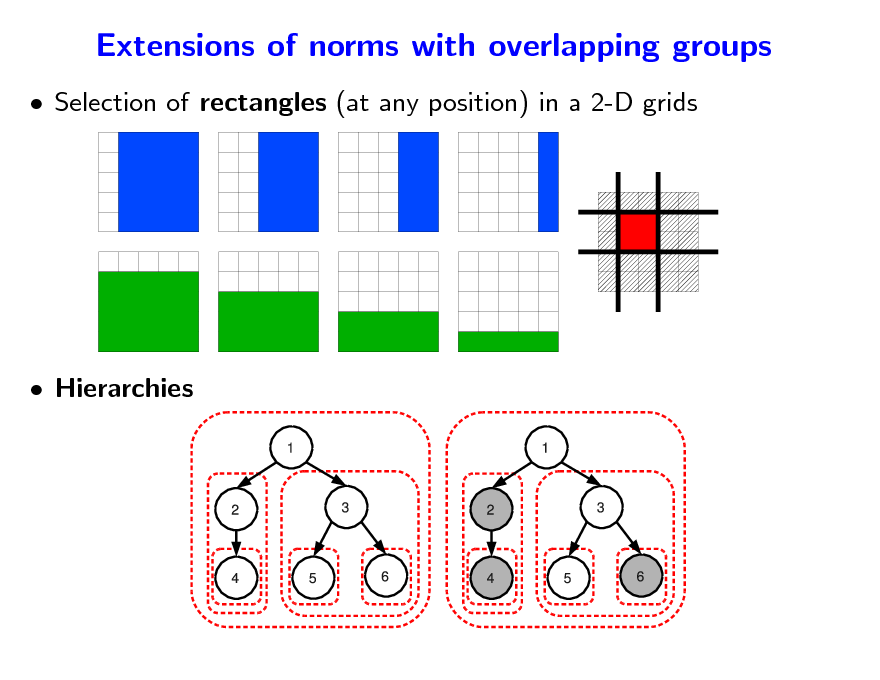

Extensions of norms with overlapping groups

Selection of rectangles (at any position) in a 2-D grids

Hierarchies

153

Submodular functions and structured sparsity Examples

From (w) to F (A): provides new insights into existing norms Grouped norms with overlapping groups (Jenatton et al., 2009a) (w) =

GH

wG

F (A) = Card {G H, GA = }

Justication not only limited to allowed sparsity patterns

154

Submodular functions and structured sparsity Examples

From (w) to F (A): provides new insights into existing norms Grouped norms with overlapping groups (Jenatton et al., 2009a) (w) =

GH

wG

F (A) = Card {G H, GA = }

Justication not only limited to allowed sparsity patterns From F (A) to (w): provides new sparsity-inducing norms F (A) = g(Card(A)) is a combination of order statistics Non-factorial priors for supervised learning: depends on the eigenvalues of XA XA and not simply on the cardinality of A

155

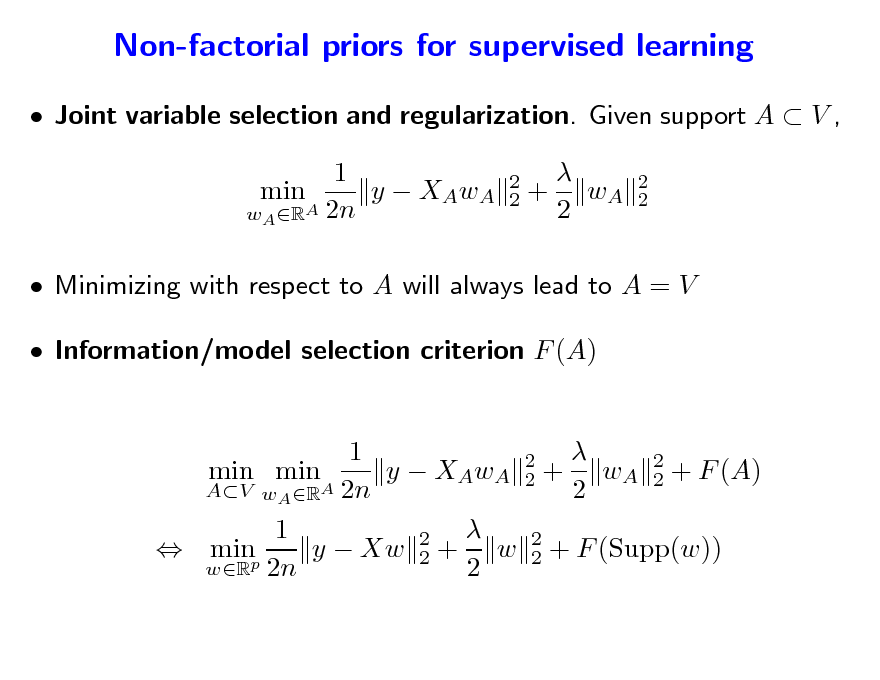

Non-factorial priors for supervised learning

Joint variable selection and regularization. Given support A V , 1 min y XAwA wA RA 2n

2 2

+ wA 2

2 2

Minimizing with respect to A will always lead to A = V Information/model selection criterion F (A) 1 2 min min y XAwA 2 + wA 2 + F (A) 2 AV wA RA 2n 2 1 2 y Xw 2 + w 2 + F (Supp(w)) minp 2 wR 2n 2

156

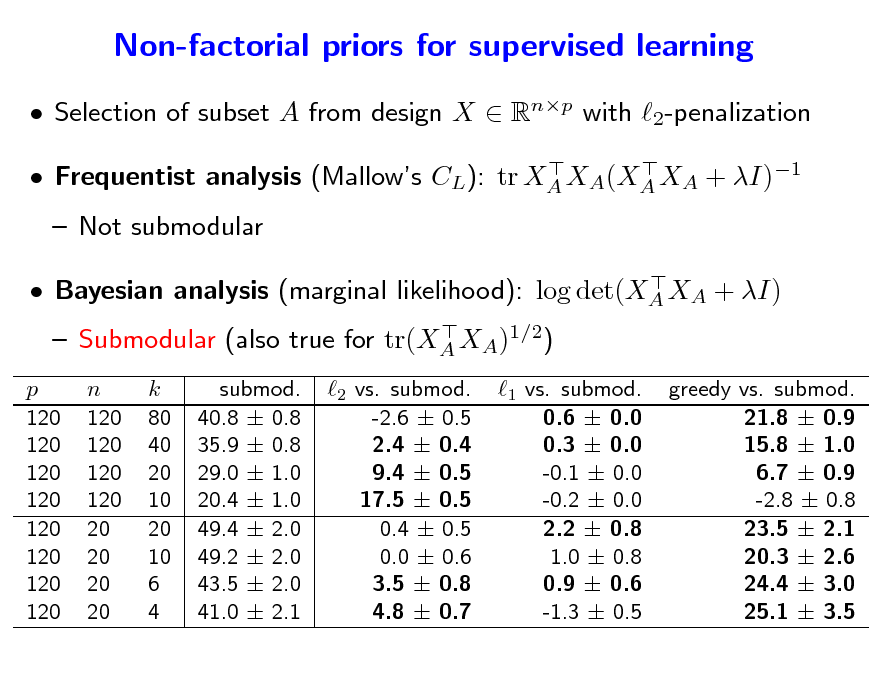

Non-factorial priors for supervised learning

Selection of subset A from design X Rnp with 2-penalization

Frequentist analysis (Mallows CL): tr XA XA(XA XA + I)1

Not submodular

Bayesian analysis (marginal likelihood): log det(XA XA + I) Submodular (also true for tr(XA XA)1/2)

p 120 120 120 120 120 120 120 120

n 120 120 120 120 20 20 20 20

k 80 40 20 10 20 10 6 4

submod. 40.8 0.8 35.9 0.8 29.0 1.0 20.4 1.0 49.4 2.0 49.2 2.0 43.5 2.0 41.0 2.1

2 vs. submod. -2.6 0.5 2.4 0.4 9.4 0.5 17.5 0.5 0.4 0.5 0.0 0.6 3.5 0.8 4.8 0.7

1 vs. submod. 0.6 0.0 0.3 0.0 -0.1 0.0 -0.2 0.0 2.2 0.8 1.0 0.8 0.9 0.6 -1.3 0.5

greedy vs. submod. 21.8 0.9 15.8 1.0 6.7 0.9 -2.8 0.8 23.5 2.1 20.3 2.6 24.4 3.0 25.1 3.5

157

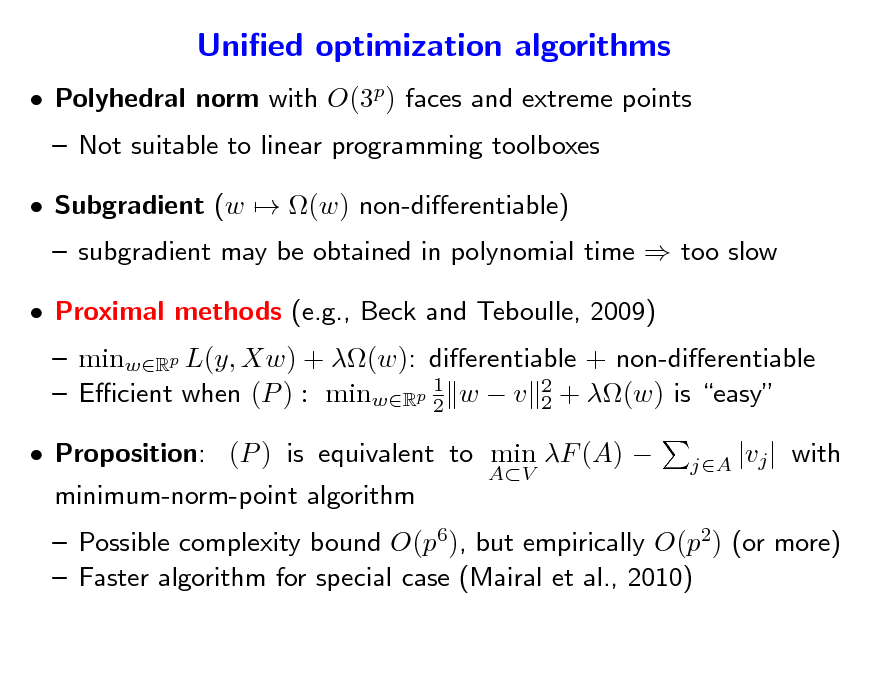

Unied optimization algorithms

Polyhedral norm with O(3p) faces and extreme points Not suitable to linear programming toolboxes Subgradient (w (w) non-dierentiable)

subgradient may be obtained in polynomial time too slow

158

Unied optimization algorithms

Polyhedral norm with O(3p) faces and extreme points Not suitable to linear programming toolboxes Subgradient (w (w) non-dierentiable)

subgradient may be obtained in polynomial time too slow minwRp L(y, Xw) + (w): dierentiable + non-dierentiable 1 Ecient when (P ) : minwRp 2 w v 2 + (w) is easy 2 minimum-norm-point algorithm

AV jA |vj |

Proximal methods (e.g., Beck and Teboulle, 2009)

Proposition: (P ) is equivalent to min F (A)

with

Possible complexity bound O(p6), but empirically O(p2) (or more) Faster algorithm for special case (Mairal et al., 2010)

159

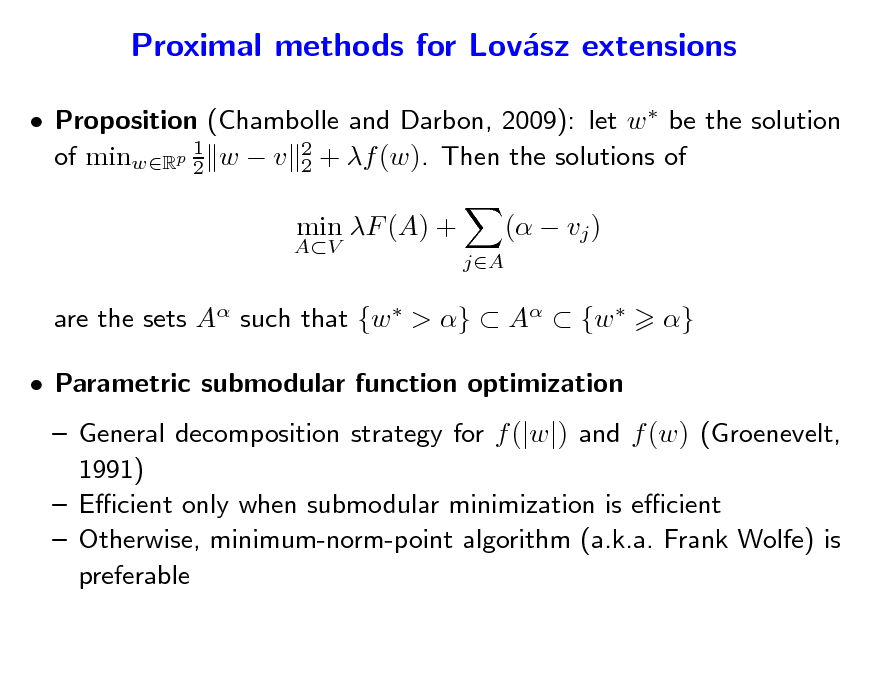

Proximal methods for Lovsz extensions a

Proposition (Chambolle and Darbon, 2009): let w be the solution 1 of minwRp 2 w v 2 + f (w). Then the solutions of 2

AV

min F (A) +

jA

( vj ) }

are the sets A such that {w > } A {w Parametric submodular function optimization

General decomposition strategy for f (|w|) and f (w) (Groenevelt, 1991) Ecient only when submodular minimization is ecient Otherwise, minimum-norm-point algorithm (a.k.a. Frank Wolfe) is preferable

160

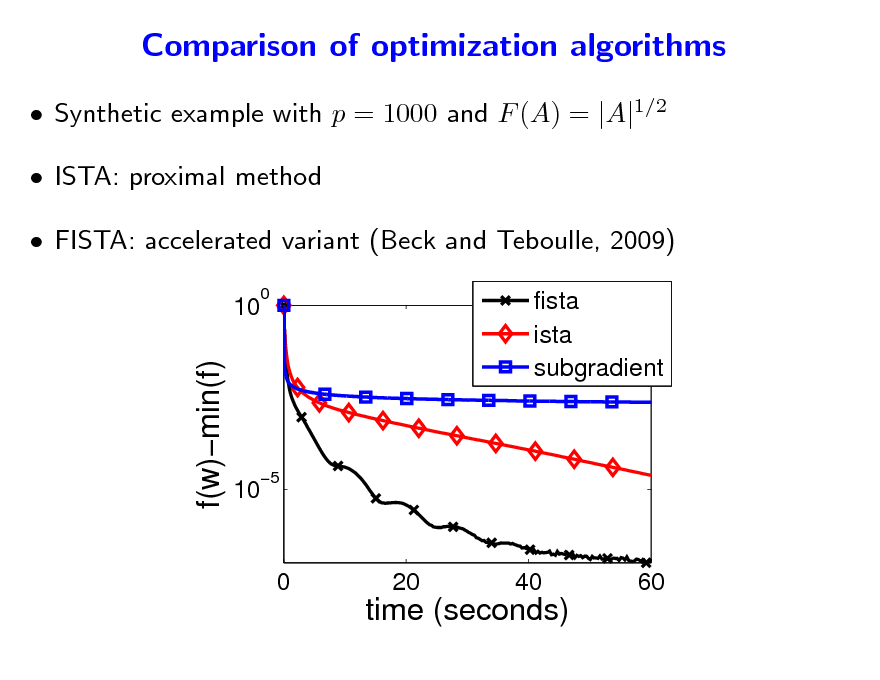

Comparison of optimization algorithms

Synthetic example with p = 1000 and F (A) = |A|1/2 ISTA: proximal method FISTA: accelerated variant (Beck and Teboulle, 2009)

10

0

f(w)min(f)

fista ista subgradient

10

5

0

20

40

60

time (seconds)

161

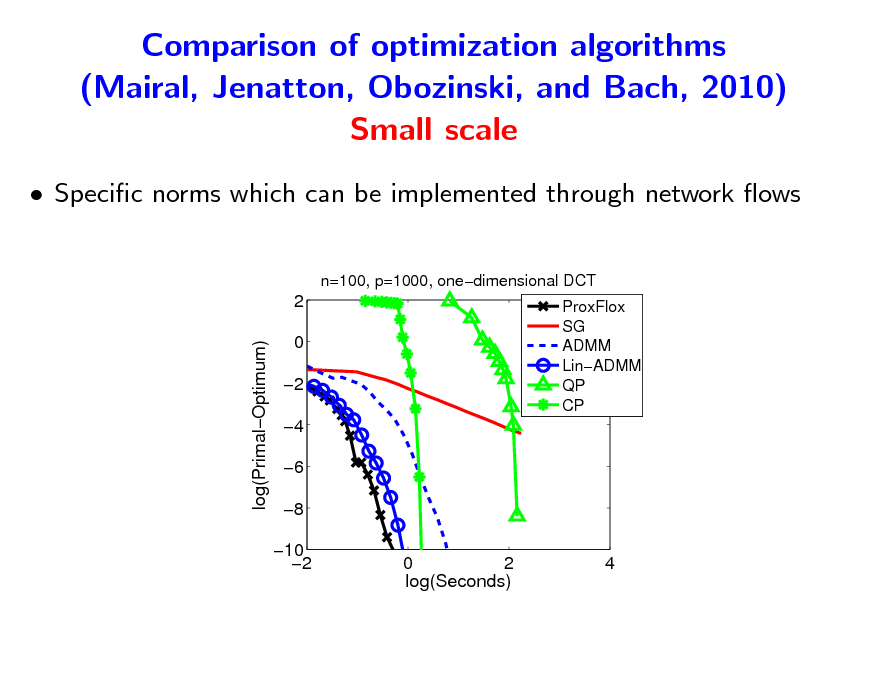

Comparison of optimization algorithms (Mairal, Jenatton, Obozinski, and Bach, 2010) Small scale

Specic norms which can be implemented through network ows

n=100, p=1000, onedimensional DCT

2 log(PrimalOptimum) 0 2 4 6 8 10 2 0 2 log(Seconds)

ProxFlox SG ADMM LinADMM QP CP

4

162

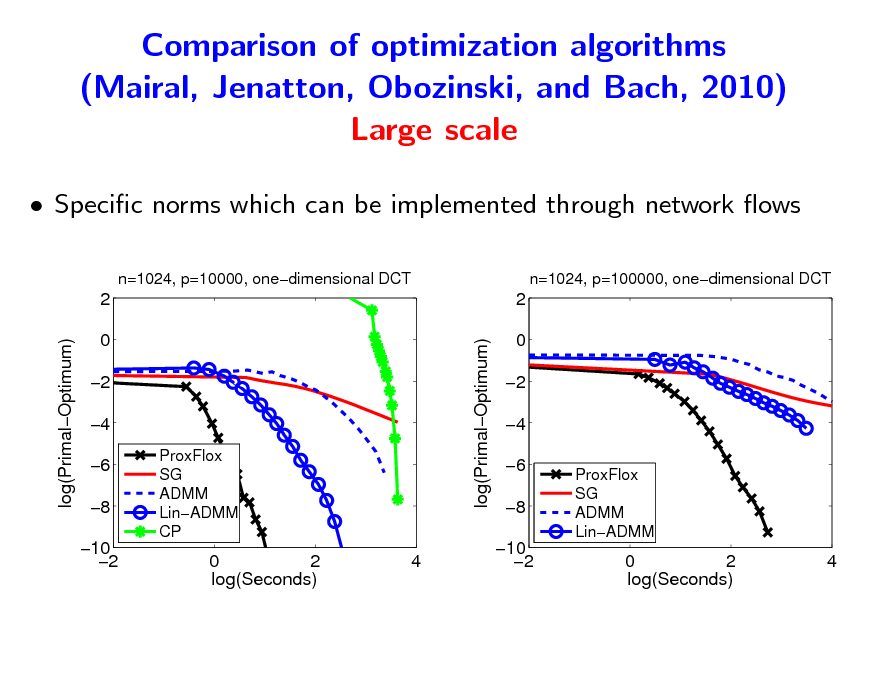

Comparison of optimization algorithms (Mairal, Jenatton, Obozinski, and Bach, 2010) Large scale

Specic norms which can be implemented through network ows

n=1024, p=10000, onedimensional DCT n=1024, p=100000, onedimensional DCT

2 log(PrimalOptimum) log(PrimalOptimum) 0 2 4 6 8 10 2

ProxFlox SG ADMM LinADMM CP

2 0 2 4 6 8 10 2

ProxFlox SG ADMM LinADMM

0 2 log(Seconds)

4

0 2 log(Seconds)

4

163

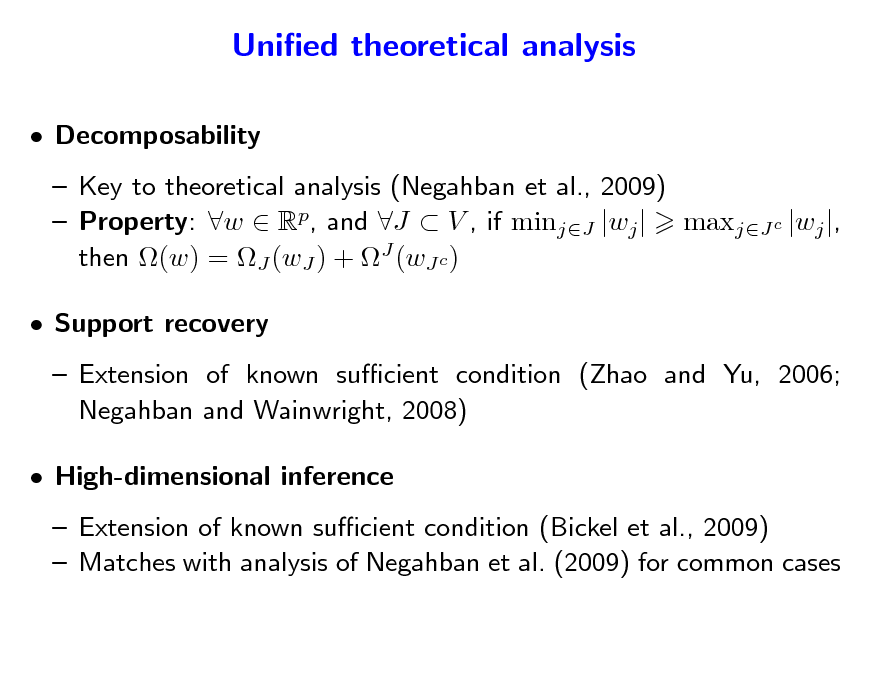

Unied theoretical analysis

Decomposability Key to theoretical analysis (Negahban et al., 2009) Property: w Rp, and J V , if minjJ |wj | maxjJ c |wj |, then (w) = J (wJ ) + J (wJ c ) Support recovery Extension of known sucient condition (Zhao and Yu, 2006; Negahban and Wainwright, 2008) High-dimensional inference Extension of known sucient condition (Bickel et al., 2009) Matches with analysis of Negahban et al. (2009) for common cases

164

![Slide: Support recovery - minwRp

Notation

1 2n

y Xw

2 2

+ (w)

(J) = minBJ c F (BJ)F (J) (0, 1] (for J stable) F (B) c(J) = supwRp J (wJ )/ wJ 2 |J|1/2 maxkV F ({k}) Assume y = Xw + , with N (0, I) J = smallest stable set containing the support of w Assume = minj,wj =0 |wj | > 0 1 Let Q = n X X Rpp. Assume = min(QJJ ) > 0

(J) n 2

Proposition

Assume that for > 0, (J )[(J (Q1QJj ))jJ c ] 1 JJ If 2c(J) , w has support equal to J, with probability larger than 1 3P (z) > z is a multivariate normal with covariance matrix Q](https://yosinski.com/mlss12/media/slides/MLSS-2012-Bach-Learning-with-Submodular-Functions_165.png)

Support recovery - minwRp

Notation

1 2n

y Xw

2 2

+ (w)

(J) = minBJ c F (BJ)F (J) (0, 1] (for J stable) F (B) c(J) = supwRp J (wJ )/ wJ 2 |J|1/2 maxkV F ({k}) Assume y = Xw + , with N (0, I) J = smallest stable set containing the support of w Assume = minj,wj =0 |wj | > 0 1 Let Q = n X X Rpp. Assume = min(QJJ ) > 0

(J) n 2

Proposition

Assume that for > 0, (J )[(J (Q1QJj ))jJ c ] 1 JJ If 2c(J) , w has support equal to J, with probability larger than 1 3P (z) > z is a multivariate normal with covariance matrix Q

165

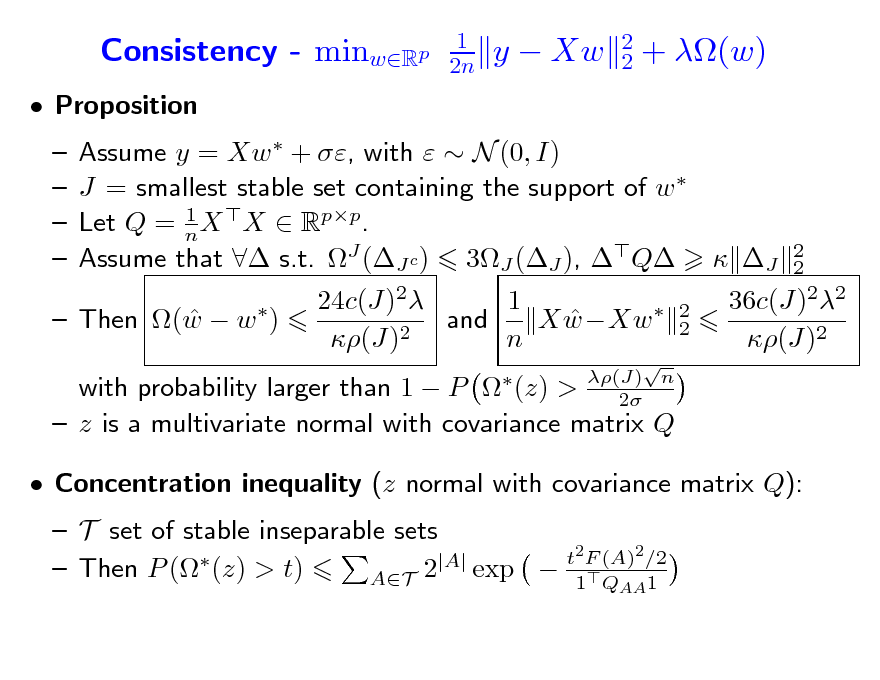

Consistency - minwRp

Proposition

1 2n

y Xw

2 2

+ (w)

Assume y = Xw + , with N (0, I) J = smallest stable set containing the support of w 1 Let Q = n X X Rpp. Assume that s.t. J (J c ) 3J (J ), Q J 24c(J)2 1 and X wXw 2 (J) n

2 2 (J) n 2

2 2

Then (w w )

36c(J)22 (J)2

with probability larger than 1 P (z) > z is a multivariate normal with covariance matrix Q Concentration inequality (z normal with covariance matrix Q): T set of stable inseparable sets t2 F (A)2 /2 |A| exp 1Q 1 Then P ( (z) > t) AT 2

AA

166

![Slide: Symmetric submodular functions (Bach, 2011)

Let F : 2V R be a symmetric submodular set-function Proposition: The Lovsz extension f (w) is the convex envelope of a the function w maxR F ({w }) on the set [0, 1]p + R1V = {w Rp, maxkV wk minkV wk 1}.](https://yosinski.com/mlss12/media/slides/MLSS-2012-Bach-Learning-with-Submodular-Functions_167.png)

Symmetric submodular functions (Bach, 2011)

Let F : 2V R be a symmetric submodular set-function Proposition: The Lovsz extension f (w) is the convex envelope of a the function w maxR F ({w }) on the set [0, 1]p + R1V = {w Rp, maxkV wk minkV wk 1}.

167

![Slide: Symmetric submodular functions (Bach, 2011)

Let F : 2V R be a symmetric submodular set-function Proposition: The Lovsz extension f (w) is the convex envelope of a the function w maxR F ({w }) on the set [0, 1]p + R1V = {w Rp, maxkV wk minkV wk 1}.

w1=w2 w3> w1>w2 (1,0,1)/F({1,3}) w1> w3>w2 (1,0,0)/F({1}) w2=w3 w1> w2>w3 (0,0,1)/F({3}) w3> w2>w1 (0,1,1)/F({2,3}) w2> w3>w1 (0,1,0)/F({2}) w2> w1>w3 w1=w3 (1,1,0)/F({1,2})

(1,0,1)/2 (1,0,0) (1,1,0) (0,0,1) (0,1,1) (0,1,0)/2](https://yosinski.com/mlss12/media/slides/MLSS-2012-Bach-Learning-with-Submodular-Functions_168.png)

Symmetric submodular functions (Bach, 2011)

Let F : 2V R be a symmetric submodular set-function Proposition: The Lovsz extension f (w) is the convex envelope of a the function w maxR F ({w }) on the set [0, 1]p + R1V = {w Rp, maxkV wk minkV wk 1}.

w1=w2 w3> w1>w2 (1,0,1)/F({1,3}) w1> w3>w2 (1,0,0)/F({1}) w2=w3 w1> w2>w3 (0,0,1)/F({3}) w3> w2>w1 (0,1,1)/F({2,3}) w2> w3>w1 (0,1,0)/F({2}) w2> w1>w3 w1=w3 (1,1,0)/F({1,2})

(1,0,1)/2 (1,0,0) (1,1,0) (0,0,1) (0,1,1) (0,1,0)/2

168

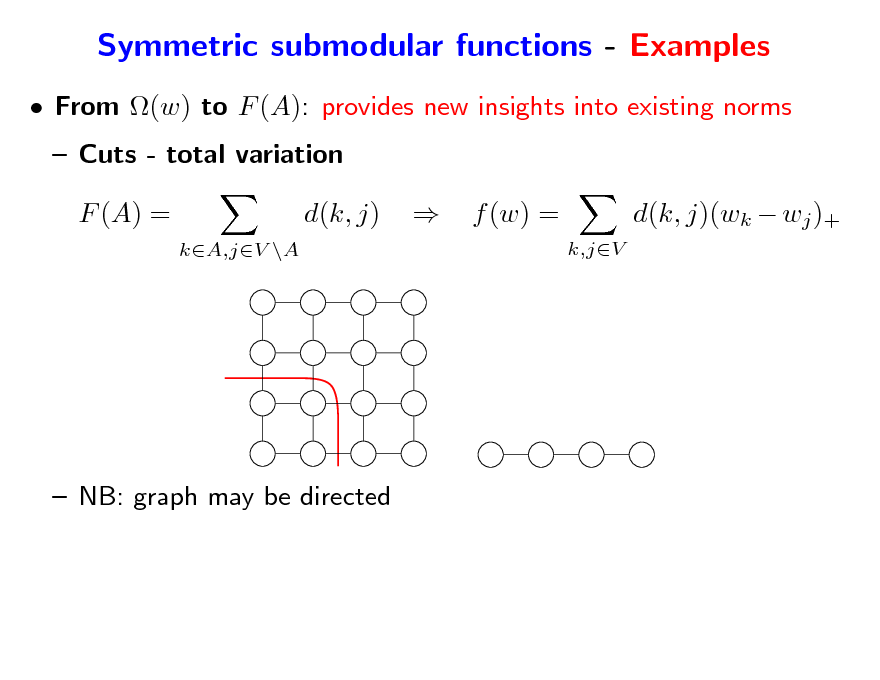

Symmetric submodular functions - Examples

From (w) to F (A): provides new insights into existing norms Cuts - total variation F (A) =

kA,jV \A

d(k, j)

f (w) =

k,jV

d(k, j)(wk wj )+

NB: graph may be directed

169

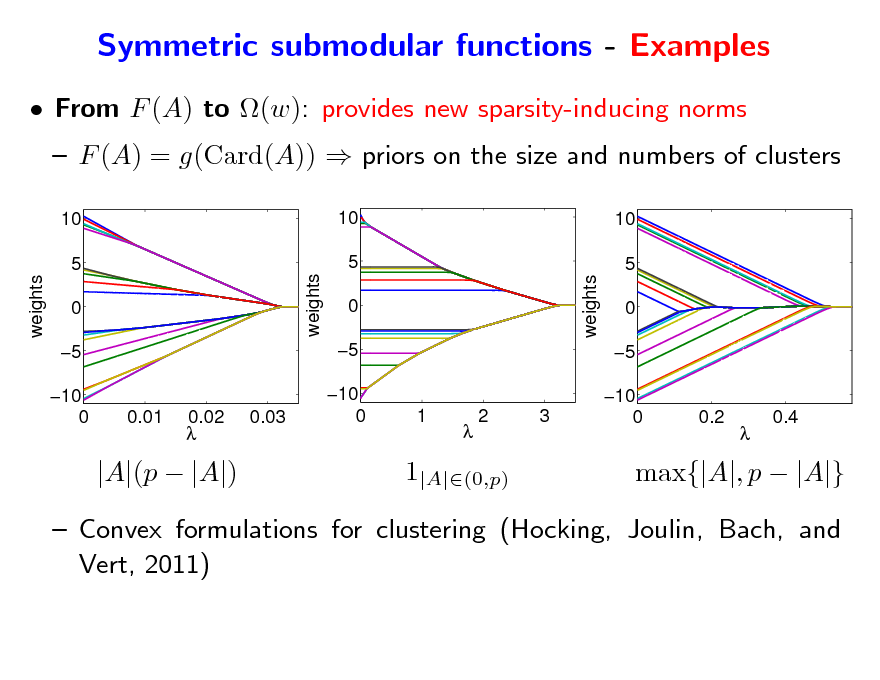

Symmetric submodular functions - Examples

From F (A) to (w): provides new sparsity-inducing norms

10 5 weights weights 0 5 10 0 10 5 0 5 10 0 weights 1 2 3 10 5 0 5 10 0

F (A) = g(Card(A)) priors on the size and numbers of clusters

0.01

0.02

0.03

0.2

0.4

|A|(p |A|)

1|A|(0,p)

max{|A|, p |A|}

Convex formulations for clustering (Hocking, Joulin, Bach, and Vert, 2011)

170

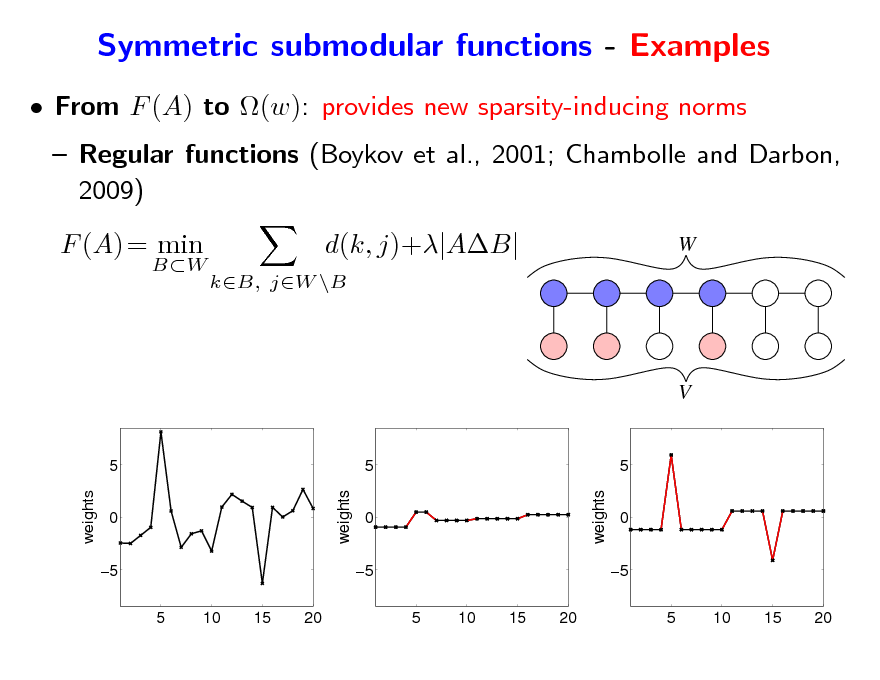

Symmetric submodular functions - Examples

From F (A) to (w): provides new sparsity-inducing norms Regular functions (Boykov et al., 2001; Chambolle and Darbon, 2009) F (A) = min

BW

d(k, j)+|AB|

kB, jW \B

W

V

5 weights weights 0 5 5 10 15 20

5 0 5 5 10 15 20 weights

5 0 5 5 10 15 20

171

![Slide: q -relaxation of combinatorial penalties (Obozinski and Bach, 2011)

Main result of Bach (2010): Problems: f (|w|) is the convex envelope of F (Supp(w)) on [1, 1]p

Limited to submodular functions Limited to -relaxation: undesired artefacts

(1,1)/F({1,2})

(0,1)/F({2})

(1,0)/F({1})](https://yosinski.com/mlss12/media/slides/MLSS-2012-Bach-Learning-with-Submodular-Functions_172.png)

q -relaxation of combinatorial penalties (Obozinski and Bach, 2011)

Main result of Bach (2010): Problems: f (|w|) is the convex envelope of F (Supp(w)) on [1, 1]p

Limited to submodular functions Limited to -relaxation: undesired artefacts

(1,1)/F({1,2})

(0,1)/F({2})

(1,0)/F({1})

172

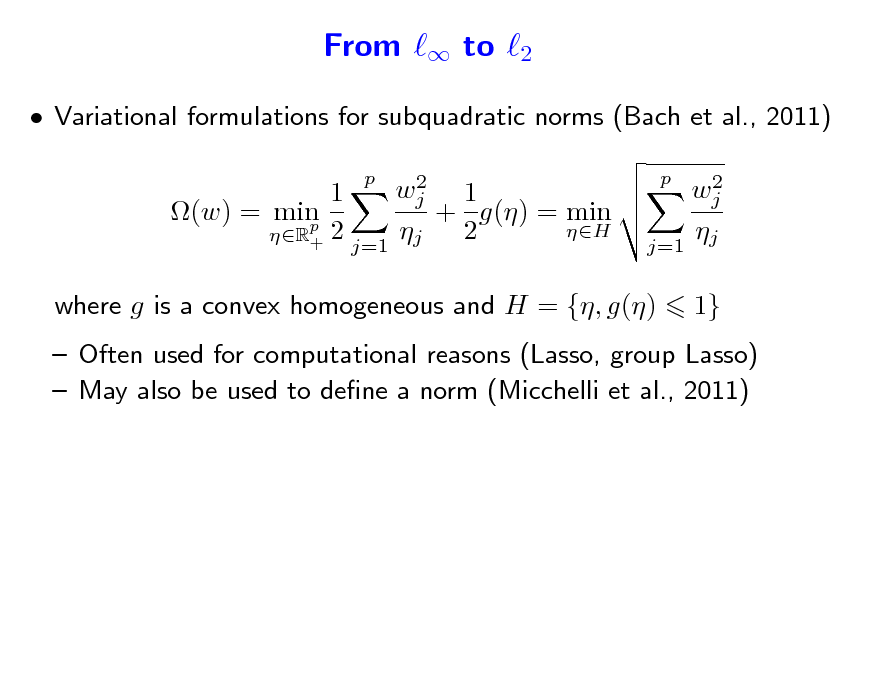

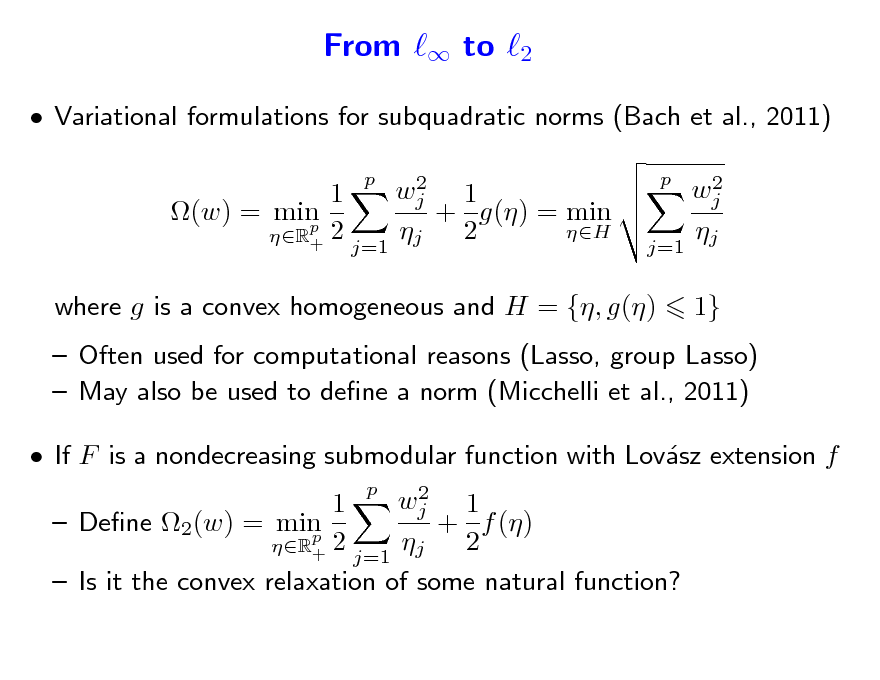

From to 2

Variational formulations for subquadratic norms (Bach et al., 2011)

2 wj 1 1 (w) = min + g() = min p 2 H 2 R+ j=1 j p 2 wj j=1 j p

where g is a convex homogeneous and H = {, g()

1}

Often used for computational reasons (Lasso, group Lasso) May also be used to dene a norm (Micchelli et al., 2011)

173

From to 2

Variational formulations for subquadratic norms (Bach et al., 2011)

2 wj 1 1 + g() = min (w) = min p 2 H 2 R+ j=1 j p 2 wj j=1 j p

where g is a convex homogeneous and H = {, g()

1}

Often used for computational reasons (Lasso, group Lasso) May also be used to dene a norm (Micchelli et al., 2011) If F is a nondecreasing submodular function with Lovsz extension f a

2 wj 1 1 Dene 2(w) = min + f () p 2 2 R+ j=1 j Is it the convex relaxation of some natural function? p

174

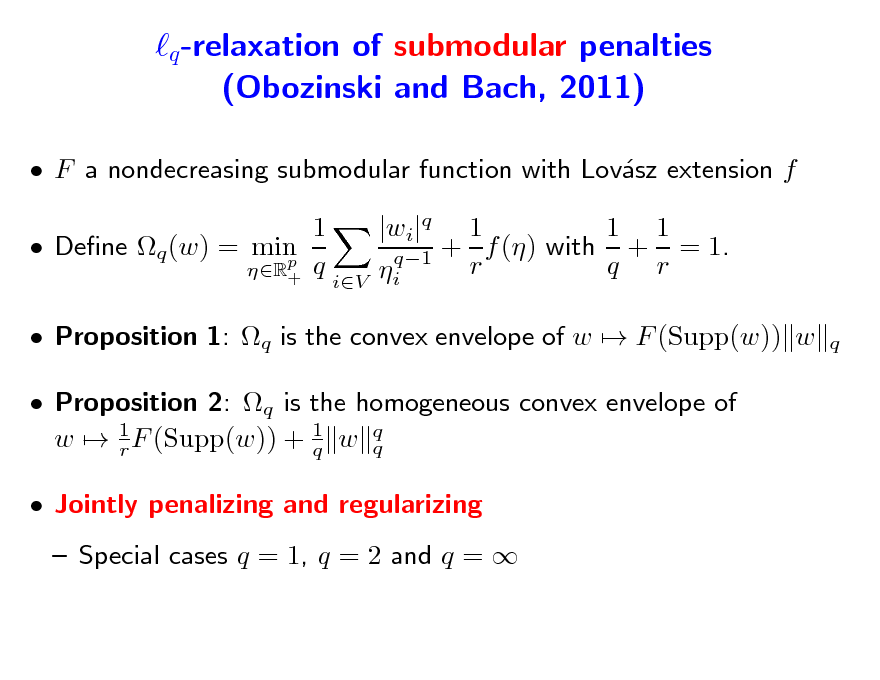

q -relaxation of submodular penalties (Obozinski and Bach, 2011)

F a nondecreasing submodular function with Lovsz extension f a 1 Dene q (w) = min p R+ q 1 1 |wi|q 1 q1 + r f () with q + r = 1. i

q

iV

Proposition 1: q is the convex envelope of w F (Supp(w)) w Proposition 2: q is the homogeneous convex envelope of w 1 F (Supp(w)) + 1 w q q r q Jointly penalizing and regularizing Special cases q = 1, q = 2 and q =

175

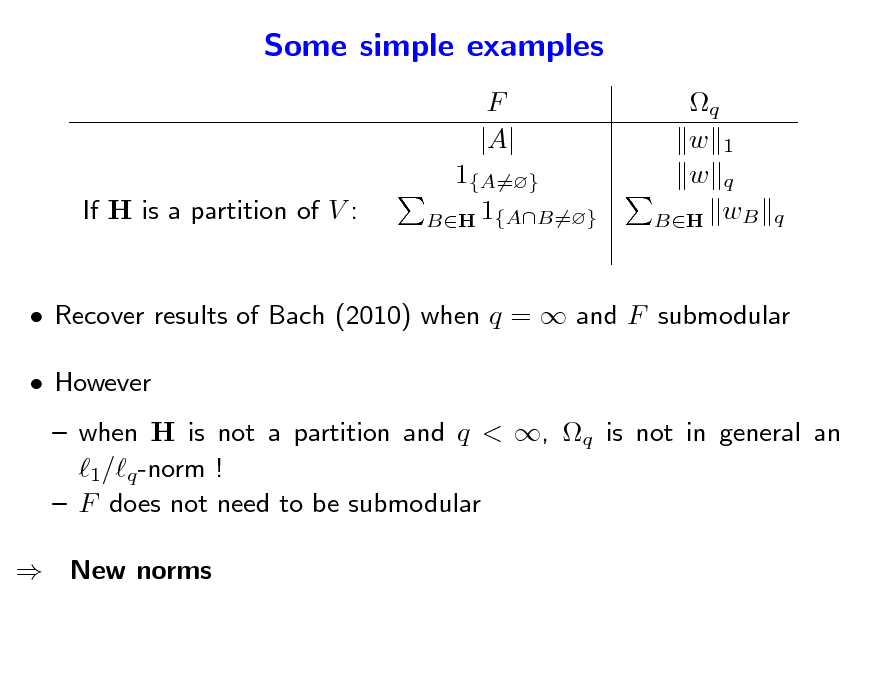

Some simple examples

F |A| q w 1 w q BH wB

If H is a partition of V :

1{A=} BH 1{AB=}

q

Recover results of Bach (2010) when q = and F submodular However when H is not a partition and q < , q is not in general an 1/q -norm ! F does not need to be submodular New norms

176

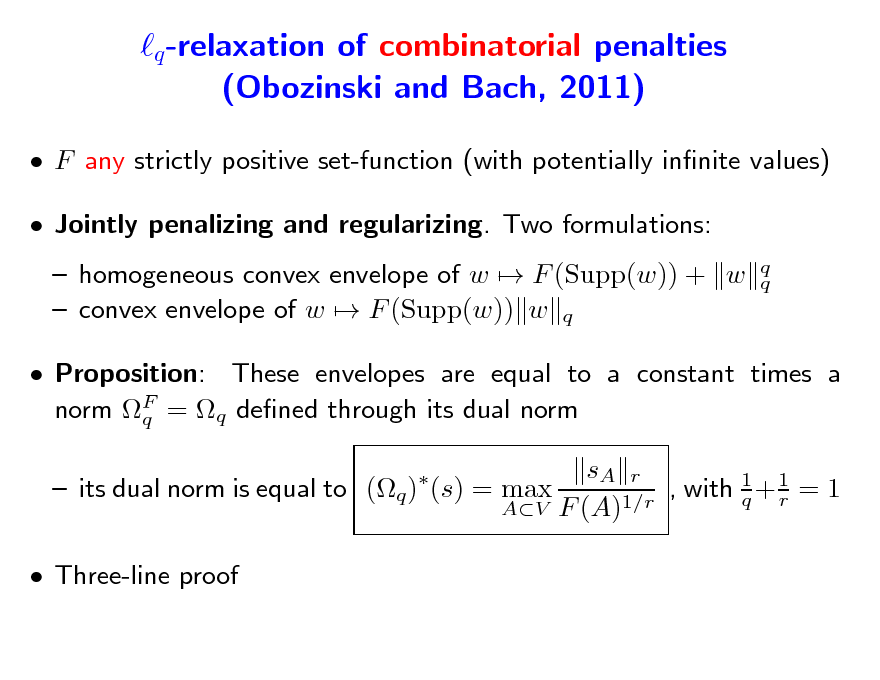

q -relaxation of combinatorial penalties (Obozinski and Bach, 2011)

F any strictly positive set-function (with potentially innite values) Jointly penalizing and regularizing. Two formulations: homogeneous convex envelope of w F (Supp(w)) + w convex envelope of w F (Supp(w)) w q

q q

Proposition: These envelopes are equal to a constant times a norm F = q dened through its dual norm q sA r its dual norm is equal to (q ) (s) = max , with 1 + 1 = 1 q r AV F (A)1/r

Three-line proof

177

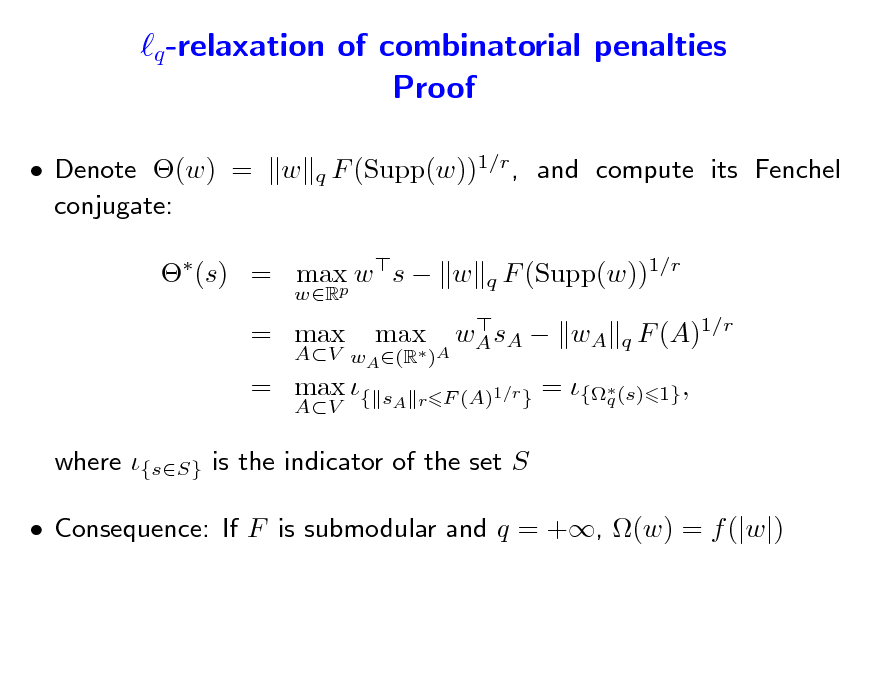

q -relaxation of combinatorial penalties Proof

Denote (w) = conjugate: w F (Supp(w))1/r , and compute its Fenchel q

(s) = max w s w p

wR

F (Supp(w))1/r q

q

= max

AV

= max {

AV wA (R )A

max

wA sA wA

F (A)1/r

1} ,

sA r F (A)1/r }

= {(s) q

where {sS} is the indicator of the set S Consequence: If F is submodular and q = +, (w) = f (|w|)

178

How tight is the relaxation? What information of F is kept after the relaxation?

When F is submodular and q = the Lovsz extension f = is said to extend F because a F (1A) = f (1A) = F (A) In general we can still consider the function : G(A) = F (1A) Do we have G(A) = F (A)? How is G related to F ? What is the norm G which is associated with G?

179

Lower combinatorial envelope

Given a function F : 2V R, dene its lower combinatorial envelope as the function G given by G(A) = max s(A)

sP (F )

with P (F ) = {s Rp, A V, s(A) F (A)}. Lemma 1 (Idempotence) P (F ) = P (G) G is its own lower combinatorial envelope For all q 1, F = G q q F (1A) = 1s = max s1A = G(A) A

sP (F )

Lemma 2 (Extension property)

(F ) (s)1

max

180

Conclusion

Structured sparsity for machine learning and statistics Many applications (image, audio, text, etc.) May be achieved through structured sparsity-inducing norms Link with submodular functions: unied analysis and algorithms

181

Conclusion

Structured sparsity for machine learning and statistics Many applications (image, audio, text, etc.) May be achieved through structured sparsity-inducing norms Link with submodular functions: unied analysis and algorithms On-going work on structured sparsity Norm design beyond submodular functions Instance of general framework of Chandrasekaran et al. (2010) Links with greedy methods (Haupt and Nowak, 2006; Baraniuk et al., 2008; Huang et al., 2009) Links between norm , support Supp(w), and design X (see, e.g., Grave, Obozinski, and Bach, 2011) Achieving log p = O(n) algorithmically (Bach, 2008)

182

Conclusion

Submodular functions to encode discrete structures Structured sparsity-inducing norms Convex optimization for submodular function optimization Approximate optimization using classical iterative algorithms Future work Primal-dual optimization Going beyond linear programming

183

References

F. Bach. Exploring large feature spaces with hierarchical multiple kernel learning. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2008. F. Bach. Structured sparsity-inducing norms through submodular functions. In NIPS, 2010. F. Bach. Convex analysis and optimization with submodular functions: a tutorial. Technical Report 00527714, HAL, 2010. F. Bach. Learning with Submodular Functions: A Convex Optimization Perspective. 2011. URL http://hal.inria.fr/hal-00645271/en. F. Bach. Shaping level sets with submodular functions. In Adv. NIPS, 2011. F. Bach, R. Jenatton, J. Mairal, and G. Obozinski. Optimization with sparsity-inducing penalties. Technical Report 00613125, HAL, 2011. R. G. Baraniuk, V. Cevher, M. F. Duarte, and C. Hegde. Model-based compressive sensing. Technical report, arXiv:0808.3572, 2008. A. Beck and M. Teboulle. A fast iterative shrinkage-thresholding algorithm for linear inverse problems. SIAM Journal on Imaging Sciences, 2(1):183202, 2009. M. J. Best and N. Chakravarti. Active set algorithms for isotonic regression; a unifying framework. Mathematical Programming, 47(1):425439, 1990. P. Bickel, Y. Ritov, and A. Tsybakov. Simultaneous analysis of Lasso and Dantzig selector. Annals of Statistics, 37(4):17051732, 2009.

184